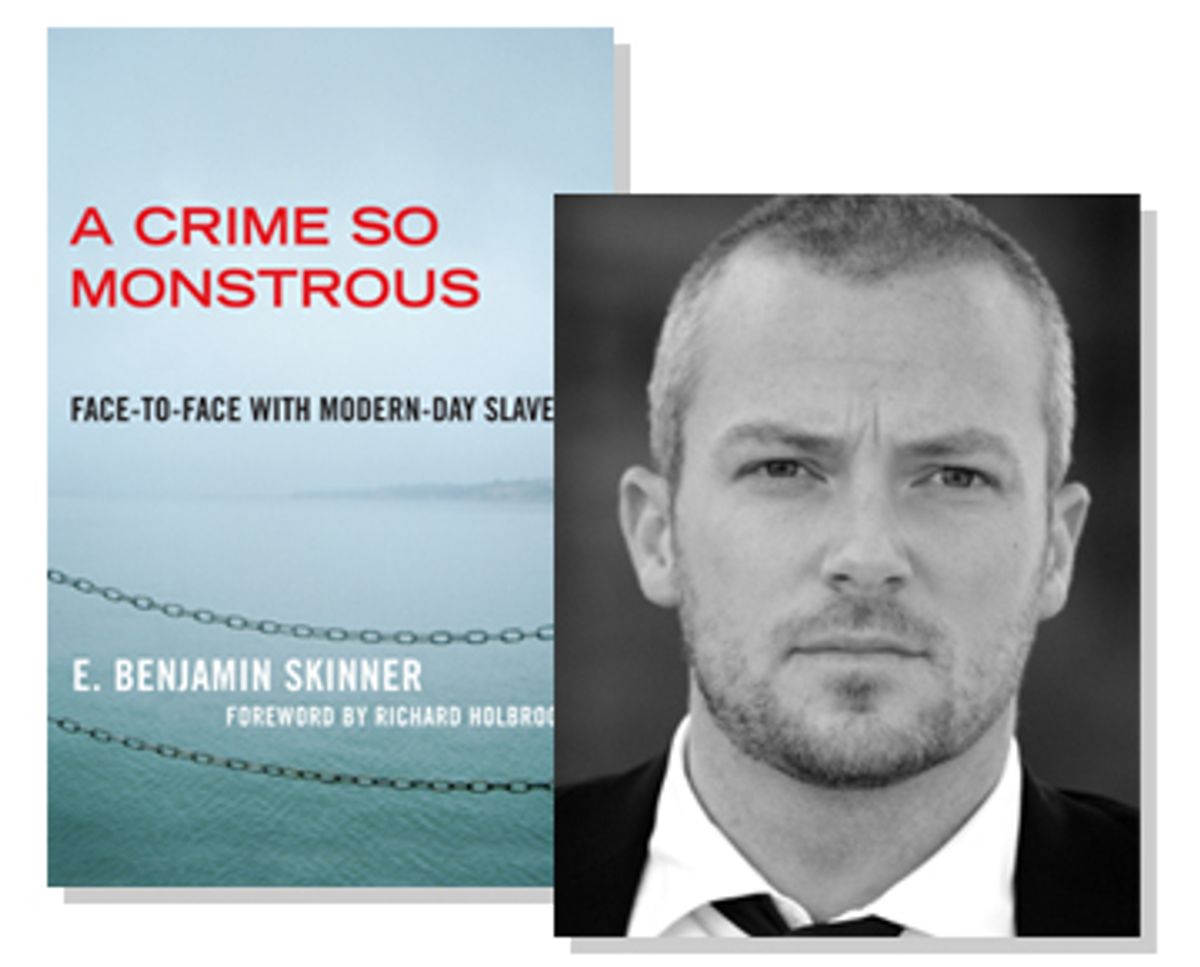

During the four years that Benjamin Skinner researched modern-day slavery for his new book, "A Crime So Monstrous," he posed as a buyer at illegal brothels on several continents, interviewed convicted human traffickers in a Romanian prison and endured giardia, malaria, dengue and a bad motorcycle accident. But Skinner, an investigative journalist, is most haunted by his experience in a seedy brothel in Bucharest, Romania, where he was offered a young woman with Down syndrome in exchange for a used car.

"There are more slaves today than at any point in human history," writes Skinner, citing a recent estimate that there are currently 27 million worldwide. One hundred and forty-three years after the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed in 1865 and 60 years after the U.N.'s Universal Declaration of Human Rights banned the slave trade worldwide, slavery -- or, as it is euphemistically called, human trafficking -- is actually thriving. It is, as Hillary Clinton has said, "the dark underbelly of globalization."

That slavery in its many forms -- debt bondage, forced domestic servitude and forced prostitution -- still exists is, indeed, shocking, mostly because it is invisible to those of us who don't know where to look for it. Skinner's great achievement is that he shines a light on the international slave trade, exposing the horrors of bondage not only through assiduous reporting and interviews with modern-day abolitionists and government officials, but by sharing the stories of several survivors. These poignant tales -- of people like Muong, a 12-year-old Dinka boy from southern Sudan, who is abducted (with his brother and mother) by an Arab slave driver; Tatiana, an Eastern European woman who is tricked into slavery when her boyfriend of six months finds her an "au pair" job in Amsterdam; and Gonoo, an Indian man in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh who inherits a debt from his father and spends his days working it off at a stone quarry -- illustrate the harsh realities of slavery while also offering some hope that former slaves can rebuild their lives.

Salon sat down with Skinner to talk about modern-day abolitionists, what's wrong with redemptions (also called "buy backs"), and why he's optimistic that slavery can be eradicated.

You infiltrated many dangerous underworlds to get these stories, often putting your life at risk by chatting up child slave brokers and negotiating to buy young women from a Russian mobster in Istanbul who'd just been released from prison. Which situation, in retrospect, was the most harrowing?

There were definitely some moments where I felt I'd made a mistake in terms of personal safety. At this point, though, I have to say that the people who are most in danger in these situations are the slaves themselves. My greatest concern going in was not "Am I going to come out whole?" but "Is there going to be some retaliation against the slaves if my cover is blown?"

I had a principle that I would not pay for a human life. You buy a human being and you can't just set them free and dump them on the economy with no resources, no support system, no rehabilitation.

When I was offered this young woman in trade for a used car at the Romani brothel in Bucharest, I could have done one of a few things: I could've paid to redeem her. I was with a couple of guys and I could've fought physically with the traffickers to get her out. Or I could've gone to the police the next day to tell them, which is what I did.

Very unsatisfying, that. You want to rip this guy's head off, right? I was shown this woman who had scars all over her arm -- she was clearly trying to kill herself to escape daily rape, and she had Down syndrome. I was so in shock. I was undercover and I had this moment where I thought, "What would my character be doing in this situation?" So I tried to smile. And I physically couldn't. I was so horrified. I looked at my translator, who had not done this kind of work before, and there was just sheer horror on his face as well. To see somebody who is in such a condition. They had put makeup on her and her makeup was running because she was crying so much.

Did the police do anything?

The response from the police was, "These are the Roma, they have their laws, they have their blood." The Roma are this incredibly oppressed and marginalized community within Romania -- and have been for centuries. That's why, I think, the major human traffickers in Romania over the past several years have been Roma.

I kept thinking of Samantha Power's book as I was reading this because you describe the reluctance of government officials to use the term "slavery" to describe what is obviously exactly that. (Power describes the same studied avoidance of the word "genocide" in "A Problem From Hell.") Colin Powell didn't use "slavery" in 2001 when he released the first Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report. Even the major piece of U.S. anti-slavery legislation, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, doesn't use the word "slavery."

There are over a dozen universal conventions and over 300 international treaties that have been signed banning slavery and the slave trade. We've all agreed that this is a crime of universal concern and it requires a robust response to stop it.

The U.S. has actually gotten better at using the term "slavery" when it's appropriate. One group that has not gotten better in this regard -- they've taken baby steps -- has been the U.N. They are so tepid and afraid of offending member states. Even in a case like Sudan, which was as egregious a form of slavery and slave raiding as you've had in the late 20th century. In 1999, at the height of slave raiding, the U.N. Human Rights Commission said, "OK, we will no longer refer to slavery, we will refer to intertribal abductions." And if you talk to U.N. officials behind the scenes, they'll say that the logic behind this is that in order to move the issue forward, we had to be diplomatic and reach this middle ground. The problem with that logic is that you lose all leverage. Abduction is not a crime against humanity -- slavery is. If it's a crime against humanity, you get hit pretty hard.

How would you get hit very hard?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 4, says slavery and the slave trade are banned worldwide. But actually, you're bringing up a good point. In terms of enforcement, the U.N. doesn't have the kind of systems built into it which can really deal with this, and that's a problem.

The U.N., which has, as part of its original mandate, the eradication of slavery and the slave trade, finds itself now at a stage where there are more slaves today than at any point in human history. And it really makes you question the viability of the model and the strength of the system.

There are philosophical differences about how to combat slavery. Some people, such as Michael Horowitz (the neocon abolitionist), have focused exclusively on sex trafficking, hoping there will be a "ripple effect" with other forms of slavery such as debt bondage and forced domestic servitude.

Nonsense.

But how do you explain this myopia? You cite so much research that shows that the other forms of slavery are even more prevalent -- in the U.S., you say, less than half of American slaves are forced prostitutes.

I don't think enough reports have come out and the ones that have come out haven't been in the right places. I think when you start getting the 700 Club talking about how the slavery of a young man in a quarry in India -- or in a brick kiln or on a farm -- is equivalent to the slavery of the Israelites and you start quoting Bible verses, then maybe we'll be getting somewhere.

Another philosophical divide among modern-day abolitionists has to do with the role of poverty. The late Senator Wellstone, who co-sponsored the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000, was adamant that poverty was a central factor but Horowitz disagreed, vehemently. Why do you think that is? It seems so obvious that poverty is the very reason so many people are forced and hoodwinked into slavery.

Paul Wellstone's view of this was basically that you can't address slavery without having targeted anti-poverty programs. When I presented this to Horowitz, he slammed his desk and said something to the effect of "The Paul Krugmans of the world would love for this to be a means for me redistributing my income to Sri Lanka." And I'll give him this: I understand his point that the end of slavery cannot wait for the end of poverty. That's not what I'm calling for and I don't think that's what Senator Wellstone was calling for.

But if you don't recognize that the primary driver of slavery today is the nexus between withering poverty of extreme marginalized communities with unscrupulous criminals, and you don't address both sides of it -- the criminal side and the socioeconomic side -- you're not going to solve this problem. As long as there's a ready source of people who are so desperate for survival that they will sell their children into slavery, as long as you don't address that, you will always have slavery. And I fundamentally feel that slavery can be ended.

Do you think the TVPA's three-tiered anti-slavery system, which evaluates countries' efforts to eradicate slavery and imposes non-trade sanctions on those who don't do anything to abolish it, works?

I think it's a good thing, but I honesty feel it has outlived its usefulness. You can only slap a country lightly on its wrists so many times and have them notice. After a while it totally loses its effectiveness.

Let's talk about the practice of Redemptions. Are these still going on and is it a viable way to chip away at slavery, buying a slave's freedom one at a time?

There's a long history of it, and not all of it is bad. I find it a very imperfect and unjust way of freeing people. You are essentially acknowledging the right of property in man, by buying them. In recent history, I can't think of any instances where it has worked and been unproblematic.

It's mostly happening in Sudan, right?

New York Times columnist Nick Kristof did it, of course, in Cambodia where he went in and bought two girls in a brothel. And he went back a year later and found that one of the girls was back in the brothel and hooked on methamphetamines.

To take our own history, Lincoln had contemplated buying all slaves from their masters and then setting them free in either Haiti or Liberia. But I think at a certain point -- and I defer to civil war scholars on this -- he realized that this was very much an imperfect justice and what needed to happen was the remaking, through force, of a society that would acknowledge that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, which was the initial promise, of course, of the Declaration of Independence.

What you have in Sudan are these evangelicals coming over with tons of hard currency in the middle of a war zone, going to one of the combatants -- in particular, one small faction of the combatants -- and saying, "OK, here's a ton of money, now go get us some slaves."

Basically funding the militia.

Exactly. And even if every one of those people was a slave and everything was on the up and up ... the devil is in the details.

You'd think that the hardest part would be freeing slaves. But once they're free, their lives are never easy. At one point in the Sudan section you say "free, but free to starve." What seems to you the best solution for helping former slaves deal with their new-found freedom?

Giving them some access to credit, healthcare, property rights and education. And psychological help.

In many of these far-off places where I was, the arbiters of law -- the people who set the rules -- are people who are benefiting from a slave economy. As long as that's the situation, you need to break the grip of those people over the system.

In your epilogue, you say, "George W. Bush did more to free modern-day slaves than any other president." However, you also criticize the Bush administration for focusing on sex trafficking to the exclusion of other forms of bondage.

The bar isn't very high. Only at the end of the Clinton years was there a recognition on the part of the executive branch that this was really an issue. But Bush deserves credit. He did more to free slaves than any president in modern history. But history doesn't grade on a curve on the subject of abolition. And he could have and should have done much more -- there's no question. The fact that there was such a narrow focus really hamstrung his efficacy on this.

Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, has called trafficking "the dark underbelly of globalization."

Which presidential candidate -- Clinton, Obama or McCain -- do you think is most passionate about abolishing modern-day slavery?

Listen, I'm not going to give Obama a pass on this. It's not clear to me that he cares about modern-day slavery -- he hasn't said a word about it. And Hillary has, certainly in the last couple of years. Though not on the trail.

But I think it is a mistake to make this a campaign issue. I think it has to be a big piece of our American foreign policy platform. It needs to be fundamentally a central piece of any meaningful new American foreign policy.

And what about John McCain?

Well, he blurbed my book. John McCain is very close with John Miller, the former head of the TIP office, which is a good sign. But no, he hasn't been a leader on this.

One of the things I found hopeful about the book is that while it's important to make policy changes and create tough anti-slavery laws, NGOs and individuals clearly play a vital role in exposing slavery. People like Rampal in India (the activist who runs Sankalp) and the Amsterdam taxi driver who helps Kayta, a sex slave, buy her freedom. So the role of the individual is important.

It is, it's extremely important. If there's a critical thing from that U.S. chapter that I was trying to get across, it's that this doesn't have to be some kind of neo-McCarthyism where you are spying on your neighbors, but just be aware of what's going on in your community.

I talk about three things that individuals can and should do. The first is becoming conscious of the reality of slavery -- becoming more attuned to the signs of what may be a trafficking or slavery situation. A key part of that is getting educated about slavery. The second thing is pressing elected officials and candidates for office on what they're going to do about it -- what creative approaches they have for combatting modern-day slavery and ending it within a generation. The third things is supporting groups like Free the Slaves (Kevin Bales' group) and Anti-Slavery International.

Abolishing slavery is clearly an all-consuming issue, something that often drives people who are involved with it to burn out or go crazy or both. How have you kept your sanity during the four years of researching this book?

The question is really how these people that operate at the pointed end of the spear keep their sanity. And the people who run trafficking shelters in Romania -- who have weekly or monthly threats from traffickers -- how they keep their sanity. For me it was much easier. You go into these situations and certainly it stays with you. When you meet somebody like this young woman in the Bucharest brothel or Gonoo or the trafficker in Haiti who offered to sell me a child for $50.

What drove you to take on this project?

You could say that abolition is in my blood. My great-great-grandfather fought with the Union Army in the Siege of Petersburg [Va.]. His uncle was a rabble-rousing abolitionist in Connecticut. And I was raised Quaker. The Quakers were the heart of the abolitionist movement in the late 18th century, early 19th century.

Fast-forward to 1999. I read Kevin Bales' "Disposable People," which is an incredibly good, earnest take on modern-day slavery worldwide. Bales' estimate of total number of slaves was 27 million -- a staggering number. The one thing that I wanted to do was to put a human face on that: to tell the stories of the slaves, the slave masters and the slave traders. And to tell the stories of those who try to free them.

Shares