Having written extensively on the Bush administration's torture policy for Salon, I concluded, in light of the shocking photographs from Abu Ghraib, that the visual medium is the most powerful and penetrating way to communicate the policy. More than two years ago, I brought the idea of making a documentary on the Bush policy to Alex Gibney, the director of "Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. Alex shared my sense of urgency, and "Taxi to the Dark Side" will premiere April 27 at the Tribeca Film Festival. (Alex is the director; I am executive producer.)

Through the film runs the story of an Afghan taxi driver, known only as Dilawar, completely innocent of any ties to terrorism, who was tortured to death by interrogators in the U.S. prison at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. "Taxi to the Dark Side" traces the evolution of the Bush policy from Bagram (Dilawar's interrogators speak in the film) to Guantánamo (we filmed the official happy tour) to Abu Ghraib; its roots in sensory deprivation experiments decades ago that guided the CIA in understanding torture; the opposition within the administration from the military and other significant figures (the former general counsel of the Navy, Alberto Mora, and former chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell, Lawrence Wilkerson, explain how that internal debate went, while John Yoo, one of its architects, defends it); the congressional battle to restore the standard of the Geneva Convention that forbids torture (centered on John McCain's tragic compromise); and the sudden popularity of the Fox TV show "24" in translating torture into entertainment by means of repetitious formulations of the bogus ticking-time-bomb scenario.

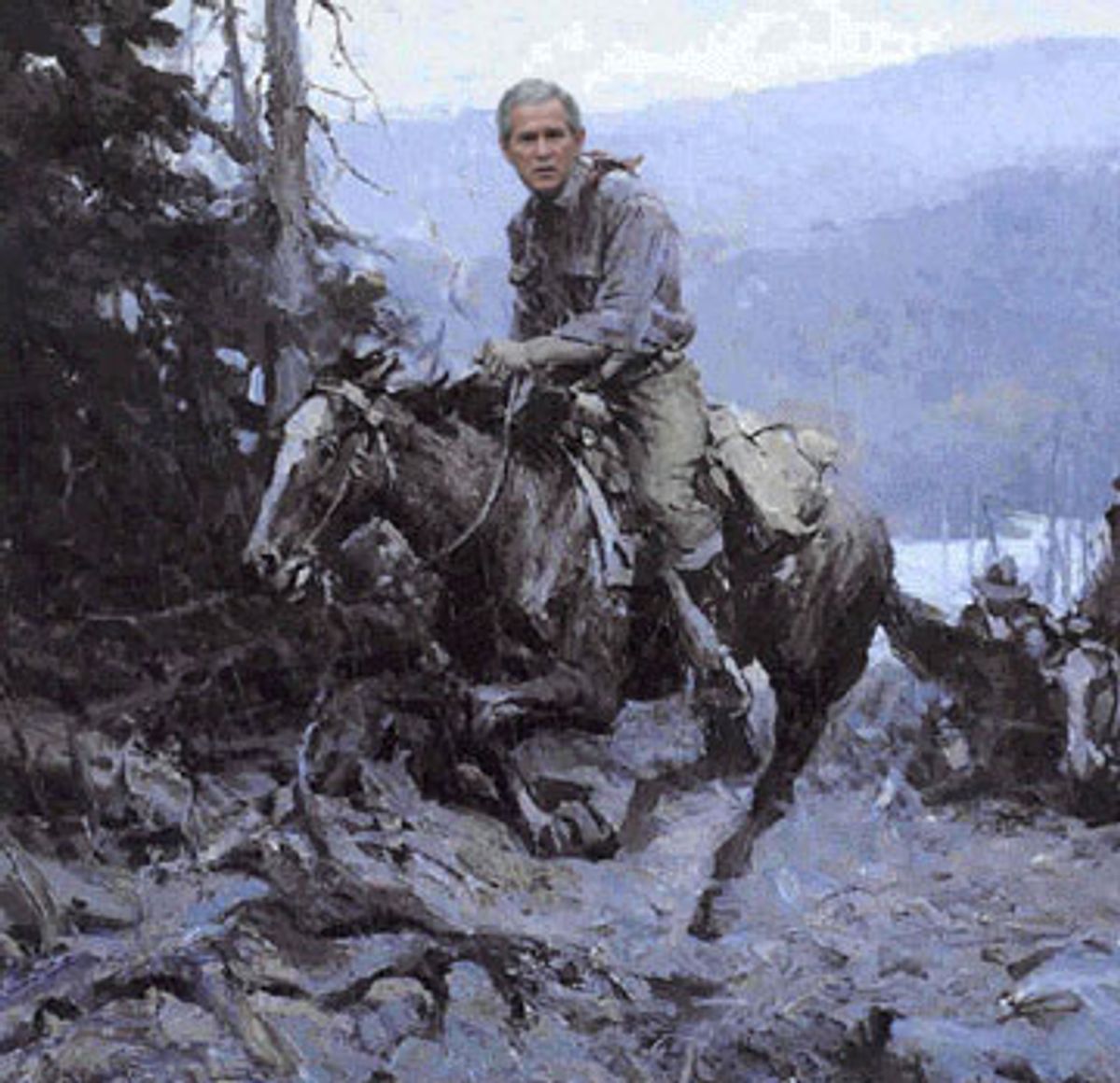

Yet "Taxi to the Dark Side" is more than an exposé of policy. Its irrefutable images are the counterpoint to the peculiar aesthetics propagated in the age of George W. Bush, in which, through the contradictory styles of softening nostalgia and hardening cruelty, the president and his followers seek to justify their actions not only to the public but also to themselves.

The notion that there might be an aesthetic that informs the Bush presidency would seem to be an unfair and artificial imposition on a man who prizes his intuition ("I'm a gut player") and openly derides complication ("I don't do nuance") -- that is, if Bush himself did not insist on the connection. Indeed, he appears on the official White House Web site, conducting a tour of the art and artifacts he has chosen to decorate the Oval Office, assuming the duty of docent himself. He holds forth on the large windows and the rug with rays of the sun emanating from the seal of the president and the provenance of his desk before getting to the artwork. (On April 19, Bush recounted to a crowd in Tipp City, Ohio, a story he has told many times, of how he commissioned his wife, Laura, to design the rug and then in defense of his Iraq policy simply remarked, "Remember the rug?")

"Each president can put whatever paintings he wants on the wall. I've chosen some paintings that kind of reflect my nature," Bush says in his video tour. He points to portraits of Abraham Lincoln ("The job of the president is to set big goals for the country") and George Washington ("You couldn't have the Oval Office without George Washington on the wall") and pats busts of Lincoln ("You can tell he's one of my favorites"), Dwight Eisenhower ("steady") and Winston Churchill ("gift of the British prime minister ... Churchill was a war leader ... resolute, tough").

Bush takes special pride in pointing out two paintings he has hung that highlight his motives and legacy. He consciously placed these pictures in the Oval Office at the beginning of his tenure to serve as prescient cultural markers. "The Texas paintings are on the wall because that's where I'm from and where I'm going," he says.

One of them, by little-known painter and illustrator William Henry Dethlef Koerner, titled "A Charge to Keep," depicts a hatless cowboy followed by two other riders galloping up a hill. Their faces are intent as they pursue some quarry in the distance that cannot be seen by others. Or are they being chased? "I love it," Bush said, further explaining his intimate feeling for the painting to reporters and editors of the Washington Times, a conservative newspaper. He offered his interpretation: "He's a determined horseman, a very difficult trail. And you know at least two people are following him, and maybe a thousand." Bush added that the painting is "based" on an old hymn. "And the hymn talks about serving the Almighty. So it speaks to me personally." When he was governor of Texas and the painting hung in his office, Bush wrote a note of explanation to his staff: "This is us."

W.H.D. Koerner, born in 1878, was a German immigrant who settled with his family in Iowa. After an early stint as a rapid-hand illustrator for the Chicago Tribune before photographs became commonplace in newspapers, he studied at the Howard Pyle School of Art, in Delaware, led by the leading illustrator in the country. Koerner then became a regular illustrator for the Saturday Evening Post, a mass magazine that appealed to small-town sentimentality and mythology in an age before the spread of radio. The magazine's trademark was its hundreds of covers produced by Norman Rockwell, a commercial artist whose ubiquitous work in advertising and his glossy but homey kitsch for the Saturday Evening Post gained him a reputation as one of the definers of everyday Americana.

The magazine used Koerner especially to provide pictures to accompany short stories about cowboys. In 1912, it gave Koerner the choice assignment of illustrating Zane Grey's "Riders of the Purple Sage." The Koerner painting that now hangs in the Oval Office first appeared as an illustration for a cowboy story called "The Slipper Tongue" in the June 3, 1916, issue. The next year, the magazine reprinted the illustration to accompany another cowboy story, "Ways That Are Dark." (Both of the writers of these short stories were forgettable figures in the western pulp fiction tradition, originated in the late 19th century by Ned Buntline, inventive publisher of Wild West dime novels and mythologizer of "Buffalo Bill" Cody and "Wild Bill" Hickok, who in the process became the wealthiest author of his time.) Two years after his illustration was first printed, Koerner resold it to Country Gentleman magazine, to go with another western called "A Charge to Keep." The editors of Country Gentleman didn't seem to mind that the picture had been used twice before by another publication.

In 1995, at Bush's inaugural as governor of Texas, his wife, Laura, selected an 18th century Methodist hymn, written by Charles Wesley, titled "A Charge to Keep." Its words in part are:

A charge to keep I have,

A God to glorify,

A never-dying soul to save,

And fit it for the sky.

To serve the present age,

My calling to fulfill:

O may it all my powers engage

To do my master's will!

After the ceremony, one of Bush's childhood friends, Joseph I. "Spider" O'Neill, managing partner of his family's oil and investment company, told him that he owned a painting, remarkably enough titled "A Charge to Keep," and that he would happily lend it to the governor. O'Neill and his wife, who attended Southern Methodist University with Laura, as it happened had also played Cupid in arranging the first date between George and Laura. Presented with the cowboy painting, Bush enthusiastically displayed it at the Governor's Mansion and now the White House.

The idea of Bush as a Christian cowboy, dashing upward and onward to fulfill the Lord's commandments, inspired him to title his campaign autobiography (written by his then communications advisor, Karen Hughes) "A Charge to Keep: My Journey to the White House." Sample: "I could not be governor if I did not believe in a divine plan that supersedes all human plans."

On the White House Web site, Bush continues his tour of his favored artwork, drawing attention to an additional painting, by regional Texan artist Julian Onderdonk, which portrays in soft beige tones one of the most iconic and historic places in the state -- the Alamo. The painting features indistinct Mexican women making tortillas in the plaza of the mission that the Mexican army besieged in the Texas war of independence of 1836. Nearly every man was killed, a massacre that became symbolic of a heroic last stand and a rallying cry for revenge. As everyone knows who has ever read one of the many histories or novels about the conflict or seen the TV series of the 1950s, "Davy Crockett," or any of the movies titled "The Alamo," such as the one featuring John Wayne as Davy Crockett, the ragtag defenders knew they were doomed but decided to fight the overwhelming Mexican army. In an incident that may be apocryphal, the commander, William Travis, drew a line in the ground, urging those who wished to leave to cross it; none did. Thus dying for the cause became the red badge of courage. Dying was "never dying," as the old hymn said, but gave birth to the republic of Texas.

Studying the racing cowboy, Bush gleans a moral lesson to stay the course, even if its end cannot be seen; his certainty that he is followed, not just by two men but also by "thousands"; and his conviction that his hot pursuit is divinely guided. As he gazes at the Alamo he is reminded that doubt and skepticism are equivalent to cowardice and capitulation, that battling to the end will lead to redemption and resurrection.

In his private study off the Oval Office, Bush displays another artifact, but one that is not featured on the Web site tour -- Saddam Hussein's pistol, seized after U.S. soldiers captured him in December 2003. "It's now the property of the U.S. government," Bush announced at a press conference shortly afterward. The president has had the gun mounted like a trophy. "He really liked showing it off," a visitor told Time magazine. In his fortress of solitude, surrounded by images of the rider and the Alamo, the determined pursuer and the last stand, the gun has become a token of Bush's inevitable victory.

Bush understands his war in Iraq through his Western artifacts -- a West, by the way, without any manifestation of Native Americans. The more resistant the reality in Iraq, the tighter he clings to the symbolism of the West. And so do those who support him. "America has a vital interest in preventing the emergence of Iraq as a Wild West for terrorists," Sen. John McCain declared on April 11. But there is a dark side to the Wild West show of the conservative mind (just as there was to the Wild West). "We have to work the dark side," said Vice President Dick Cheney a week after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

One week after Cheney's statement, on Sept. 25, 2001, the Department of Justice sent the White House a memo titled "The President's Constitutional Authority to Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists and Nations Supporting Them." The memo declared that there were "no limits" on the president's powers to wage a war without any known end and that the president was invested with powers to stage "preemptive" strikes against any target he designates at any time without consulting Congress.

On Aug. 1, 2002, another memo, co-written by the chief of the Office of Legal Counsel of the Justice Department, Jay Bybee, and his deputy assistant, John Yoo, who had been the author of the earlier Sept. 25, 2001, memo, laid out the rationale for a new policy on torture.

On Jan. 25, 2002, White House legal counsel Alberto Gonzales stated in a memo to President Bush that the Geneva Conventions Common Article Three to which the U.S. is a signatory and that forbids torture was obsolete: "In my judgment, this new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva's strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners and renders quaint some of its provisions."

Now, Bybee and Yoo redefined torture. In their memo they recast techniques illegal under the Geneva Conventions as acceptable: "Physical pain amounting to torture must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death." Bush promptly ordered implementation of the new policy. Thus the decision whose grotesque consequences were enacted at Abu Ghraib began at the top of the chain of command. When the Bybee memo was exposed the administration declared that it had been rescinded. But the "coercive interrogation techniques," as Bush calls them, continued. "This program won't go forward if there's vague standards applied like those in the Geneva Conventions," he said on Sept. 15, 2006. He assailed Congress for trying to legislate against torture and reiterated that Article Three is "so vague."

An obsession with torture has not been restricted to the White House. It has spread into the larger culture, especially through a popular TV series, on Rupert Murdoch's Fox entertainment channel, called "24." Every week, a fictional hero named Jack Bauer, an agent for a fictional government Counter Terrorist Unit, races the clock, in fantastic ticking-time-bomb scenarios, to thwart terrorist plots. Bauer's favored method is torture. Agent Bauer has shot one suspect's wife, staged a fake execution of another's child, electrocuted another bad guy and even tortured his own brother. Bauer is also tortured from time to time, fostering an impulse for vengeance. From 2002 through 2005, the Parents Television Council, a watchdog group, counted 67 torture scenes on "24."

In March 2006, in Washington, the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank, sponsored a panel discussion devoted to "24," titled "America's Image in Fighting Terrorism: Fact, Fiction, or Does It Matter?" Lending verisimilitude to the celebration of the fictional TV series, Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff was the first speaker. "Frankly," he said about the program, "it reflects real life." He expressed a wish that terror investigations could be more like those on TV. "I wish we could have a rapid execution of tasks within 24 hours," Chertoff said. Howard Gordon, the show's executive producer, conceded, "When Jack Bauer tortures, it's in a compressed reality."

The moderator, right-wing talk show host Rush Limbaugh, boasted, "Everybody I've met in the government that I tell I watch this show, they are huge fans. Vice president's a huge fan. Secretary [of Defense Donald] Rumsfeld is a huge fan." In fact, on the same day as the Heritage Foundation event the producer and director of "24" were feted at a private lunch at the White House. Jane Mayer of the New Yorker reported: "Among the attendees were Karl Rove, the deputy chief of staff; Tony Snow, the White House spokesman; Mary Cheney, the Vice-President's daughter; and Lynne Cheney, the Vice-President's wife, who, [Joel] Surnow [the show's director] said, is 'an extreme '24' fan.'"

But "24" is more than the return of the repressed. Administration officials seem to view it as the war on terror in its ideal form, utterly without "quaint" restraints or actual frustrations. "24" is torture without excuses or embarrassment. Bush administration fans apparently project themselves onto agent Bauer, whose methods are always cheered and whose own suffering ends within the hour. For them it is all more real than real life.

John Yoo, in his book justifying torture, "War by Other Means," published in 2006, even cited "24" as a legitimate intellectual proof for the policy he helped put into place: "What if, as the popular Fox television program '24' recently portrayed, a high-level terrorist leader is caught who knows the location of a nuclear weapon?" he writes about the most grandiose of ticking-time-bomb plots. This sort of scenario invariably prompts agent Bauer's remorseless threat to terrorist suspects: "You are going to tell me what I want to know. It's just a question of how much you want it to hurt." Thus the lines between fact and fiction, reality and kitsch, and policy and entertainment are blurred.

The distance between the cowboy paintings Bush proudly displays in the Oval Office and the secret-agent torture porn that his administration officials not so secretly watch with envy reflects a yawning chasm in the sensibility of kitsch. Koerner's Western pictures depict an idealized past, where never is heard a discouraging word. At the Saturday Evening Post, he joined with Norman Rockwell to create the brush strokes of a warming nostalgia.

These enduring images infused Reaganism with its emotional culture. Ronald Reagan, after all, had been raised at the turn of the century in small-town Illinois and became a contract player in Hollywood's dream factory. Communicating kitsch was second nature to him. The perfect representation came in the TV commercial for his reelection campaign in 1984. As an American flag was raised in a small town, the voice-over intoned: "It's morning again in America." The past was present and all was right with the world.

Now, kitsch has been radically remade. No longer evoking nostalgic utopianism, kitsch releases the compulsions of fear. Under Bush, kitsch has been transformed from sentimentality into sadomasochism.

Shares