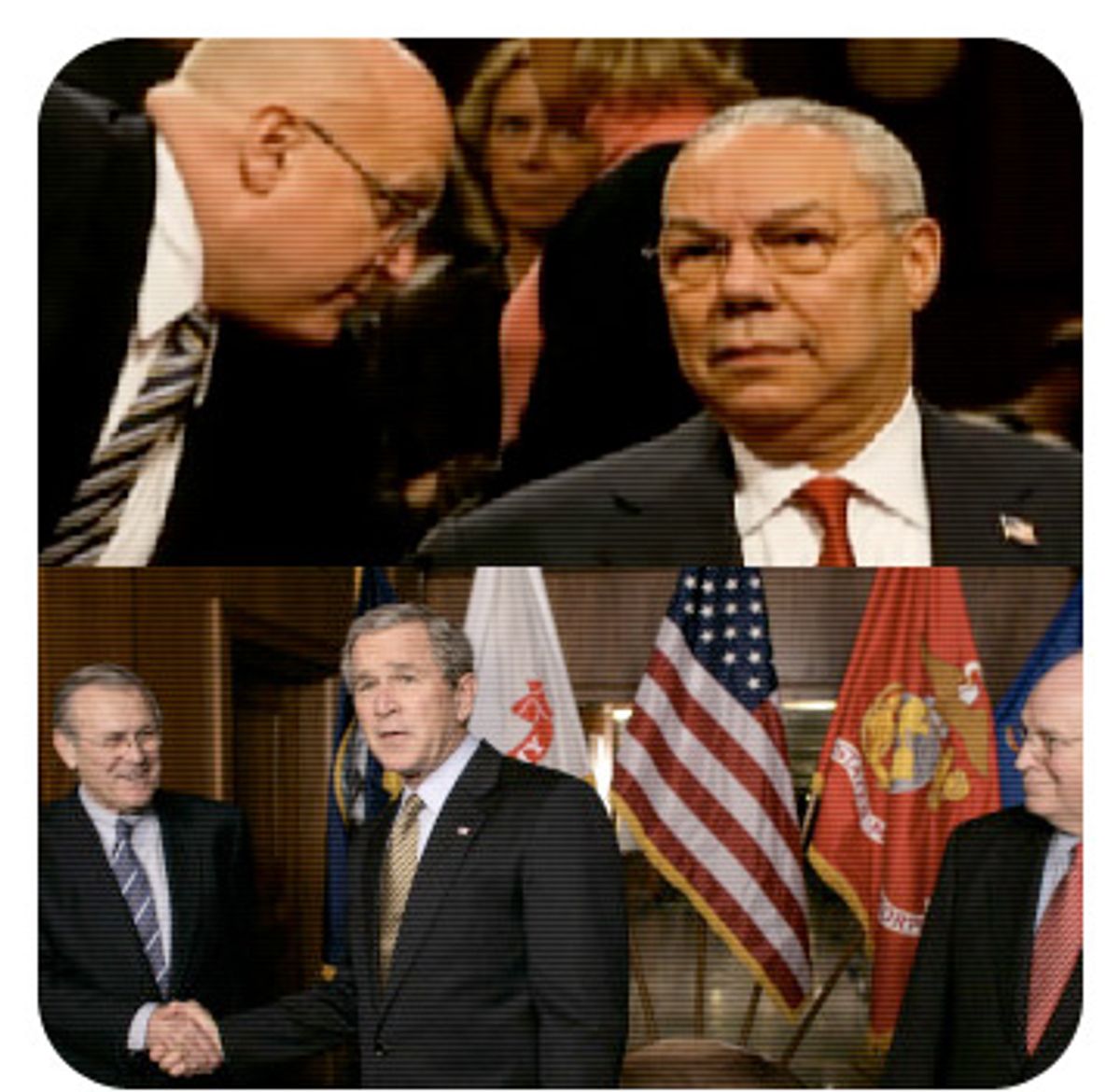

Every movement, gesture and tic of the Bush administration is shadowed by its past. When National Intelligence Director Michael McConnell was deployed politically to overawe timorous legislators into approving unlimited and warrantless domestic surveillance, he was acting in the shadow of former CIA Director George Tenet, whose presence was used to lend credibility to intelligence being fixed to suit arguments for the invasion of Iraq. As Gen. David Petraeus prepares to deliver his report in September on the "surge" in Iraq, he is elevated into the ultimate reliable source, just as former Secretary of State Colin Powell's sterling reputation was exploited for his delivery of the case for invasion before the United Nations Security Council on Feb. 5, 2003, a date that will live in mendacity, for every statement he made was later revealed to be false; Powell regretted publicly that it was an everlasting "blot" on his good name. Meanwhile, during the dog days of August, the president's aides are preparing the fall public relations campaign to envelop Petraeus' report. On cue, neoconservative organs spew out good news of "progress on the ground" and thrash critics as "defeatist." "Defeatists in Retreat" trumpets William Kristol's latest screed in the Weekly Standard, repackaging old themes once again.

Behind the display of bravado, the West Wing is seized with anxiety. Any rustle in the brush, any sudden noise, upsets the president's aides. As they try to regain their composure and confidence, recalling the glory days when they constituted themselves as the White House Iraq Group, or WHIG, a P.R. juggernaut before the invasion, they know who and what they have buried along the way and fear their return.

The release of a documentary on the administration's failures in Iraq, "No End in Sight," directed by Charles Ferguson, has the White House spooked. Bush's aides are not worried because the film is brilliantly shot and edited, or because it is compelling, but because of what -- or whose appearance -- it might augur to upset their September rollout.

The film features three former administration officials speaking on camera as unreserved critics of prewar and postwar planning: Powell's former chief of staff, Col. Lawrence Wilkerson; Powell's former deputy secretary of state, Richard Armitage; and former U.S. ambassador Barbara Bodine, a senior member of the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance in Iraq, closely aligned with Powell.

Wilkerson and Bodine have spoken out before. But Armitage's debut in particular has the White House fuming and fretting that it somehow signals Powell's emergence as a full-throated critic in the middle of the September P.R. offensive. National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley, according to sources close to him, has voiced anger and concern about whether Powell will step forward and what he might say, and other presidential aides are wondering how to cope with that nightmarish possibility.

Two months ago, Powell declared the surge a near-certain failure. On June 10, on NBC's "Meet the Press," he declared, "The current strategy to deal with it, called a surge -- the military surge, our part of the surge under General Petraeus -- the only thing it can do is put a heavier lid on this boiling pot of civil war stew ... And so General Petraeus is moving ahead with his part of it, but he's the one who's been saying all along there is no military solution to this problem. The solution has to emerge from the other two legs, the Iraqi political actions and reconciliation, and building up the Iraqi security and police forces. And those two legs are not -- are not going well. That part of strategy is not going well."

Hadley and others are taking Powell's early skepticism toward the surge and willingness to express it as a potential sign that he will swoop down on them just after Petraeus asks for more forbearance for the president's policy. Powell is the White House's ticking-time-bomb scenario. He was Petraeus before Petraeus, the good soldier before the good soldier, window-dressing before window-dressing. The White House aides' fear of Powell reflects their guilt, if not their stricken consciences, over his disposal. Powell was used, ruined and tossed overboard. His warnings were ignored, his loyalty was abused, and when he no longer served Bush's purposes he was unceremoniously discarded.

Throughout the excruciating years of his slow destruction, no one served Powell less ably than Powell. To the degree that his abusers and tormentors may be haunted, he is more haunted. Powell's aides are now on the front line of criticism against the administration, while he obviously simmers, pretending to be happily retired. He travels the country delivering motivational speeches, a theater of make-believe, as though he were the same Colin Powell as before Bush. While he preaches his secrets of success, he can see the neoconservative architects of failure in Iraq who demonized him distributed among the leading Republican candidates for president. There is not one among them who does not boast neocon dominance of his foreign policy circle. Powell's absence cedes the political terrain to those who ousted him from office. Notwithstanding his tarnished reputation, he has a final chance to regain his dignity and at least some of his previous standing by stepping forward at the crucial hour. Does he accept his marginalization as permanent? He is Banquo's ghost, but will he make an appearance at Bush's banquet?

Hadley and Co. worry that Powell may be secretly writing a memoir that would expose their hidden history, though Powell has said he will not produce a sequel to his inspirational autobiography. One of the most significant stories for which Powell would be an ideal narrator is his own mistreatment and misjudgments. Were Powell to decide to stop serving his false friends and instead to serve history, or if he were to decide simply to serve the truth before Bush perpetrates more damage, he would have to start at the beginning.

When did he realize that as secretary of state he was not the principal foreign policy advisor to the president? Was it when he was appointed in December 2000 as secretary-designate?

Being an experienced bureaucrat at the most senior levels of government, having been national security advisor and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, why did he not make common cause with Brent Scowcroft and other experienced senior personnel with whom he had long relationships to get an alternative point of view to a president whose only policy choices were being filtered through Dick Cheney's neocon structure? As chairman of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, Scowcroft was politically isolated, forced to speak out occasionally in Op-Ed pieces and interviews. When Scowcroft published his Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal on Aug. 15, 2002, "Don't Attack Saddam," where was Powell and what did he say to Scowcroft?

Why did Powell not join Scowcroft in expressing concern about the rehabilitation of Iran-Contra convicted felon Elliott Abrams, appointed on June 1, 2001, as special assistant to the president and senior director on the National Security Council for Near East and North African Affairs. And why did Powell make no effort to block Cheney's neocon takeover of the administration?

On Oct. 5, 2004, two weeks before he was ousted by Bush as chairman of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, Scowcroft objected to Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon's advisor Dov Weisglass' statement in favor of freezing the Oslo peace process. Why didn't Powell step in to help Scowcroft against Abrams' manipulation of information flowing to the president about what Weisglass was saying? Was Powell aware that Abrams was working with Weisglass?

Powell watched as the neocons filled strategic positions throughout the administration. Why did he agree to the appointment of John Bolton as undersecretary for arms control and international security on May 11, 2001, and keep him on instead of firing him for reporting to Cheney rather than to him? Why did he permit Bolton to hire neocon David Wurmser as a special advisor?

On Sept. 17, 2001, one week after 9/11, Bush signed a "top secret" document to begin planning the invasion of Iraq. Powell was later reported to have said at meetings at the time, "Jeez, what a fixation about Iraq." In April 2002, Bush advised Condoleezza Rice that he was prepared to move against Saddam. Did he advise Powell? When did Powell learn what Bush had told Rice? Was he cut out?

In February 2003, Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and Gen. Richard Meyers briefed Saudi ambassador Prince Bandar on the Iraq war plans. Had they already briefed Powell? If he was cut out, what did he do subsequently?

On May 16, 2004, Powell stated on "Meet the Press" that his Feb. 5, 2003, presentation before the United Nations Security Council on weapons of mass destruction was inaccurate. When he agreed to make the administration's case, why did he take only two personal staffers (Col. Wilkerson and executive assistant Craig Kelly) to the CIA to review what Cheney, Scooter Libby and Paul Wolfowitz had prepared and/or distorted, instead of bringing knowledgeable members of his own intelligence service, the State Department Intelligence and Research Bureau (INR), to protect him?

On Feb. 5, 2004, I quoted Greg Thielman, former director of the Strategic, Proliferation and Military Affairs Office of INR, in Salon: "He didn't have anyone from INR near him. Powell didn't want to know what was true or not. He wanted to sell a rotten fish. At some point, Powell decided there was no way to avoid war. His job was to go to war with as much legitimacy as we could scrape up." Why did Powell cut out his own people to his own ultimate detriment?

The documentary "No End in Sight" depicts the creation of the multivolume "Future of Iraq" study prepared by Powell's State Department staff for the reconstruction of Iraq after the war. When Rumsfeld and Deputy Secretary of Defense Wolfowitz rejected the study and blackballed Powell's staff, what did he do to counter them, if anything?

Eventually, history will answer these questions. But in September, Bush will attempt to impose his endgame for Iraq, a continuation of his policy, until he hands off the disaster to his successor. Petraeus is Bush's agent, just as Powell had been. Bush and his White House dread the "mockery" of Powell's "horrible shadow." If Powell remains silent in September it will be his last act of acquiescence as a spectral being.

Haunted by Banquo's ghost, Macbeth says, "If charnel-houses and our graves must send/ Those that we bury back, our monuments/ Shall be the maws of kites." And when Banquo's ghost vanishes, still plagued with the guilt of Banquo's murder, Macbeth cries out: "Hence, horrible shadow! Unreal mockery, hence!"

Shares