"The surge worked."

So insistently do the media's mainstream and conservative commentators repeat the Iraq success meme -- echoing the mantra of George W. Bush and John McCain -- that to probe its premises and assumptions is not permitted. To question the success of last year's troop escalation supposedly implies a negative assessment of the performance of American soldiers and Marines and may even imperil their morale, creating a frame that stifles dissent. But now McCain himself has inadvertently reopened real debate on the subject by claiming that strategies and tactics used to quell the Sunni insurgency long before the surge troops arrived in Iraq should nevertheless be attributed to the surge. Indeed, the surge is so brilliant and so powerful, according to McCain, that it makes things happen in the past as well as in the present and the future.

That must be what passes for "maverick" thinking, although there are certainly other names for it. For those of us who remain tethered to reality, however, the success of the surge must be measured in a context that accounts for many other factors -- as must the simple assertion that we are winning the war in Iraq as a result of the escalation.

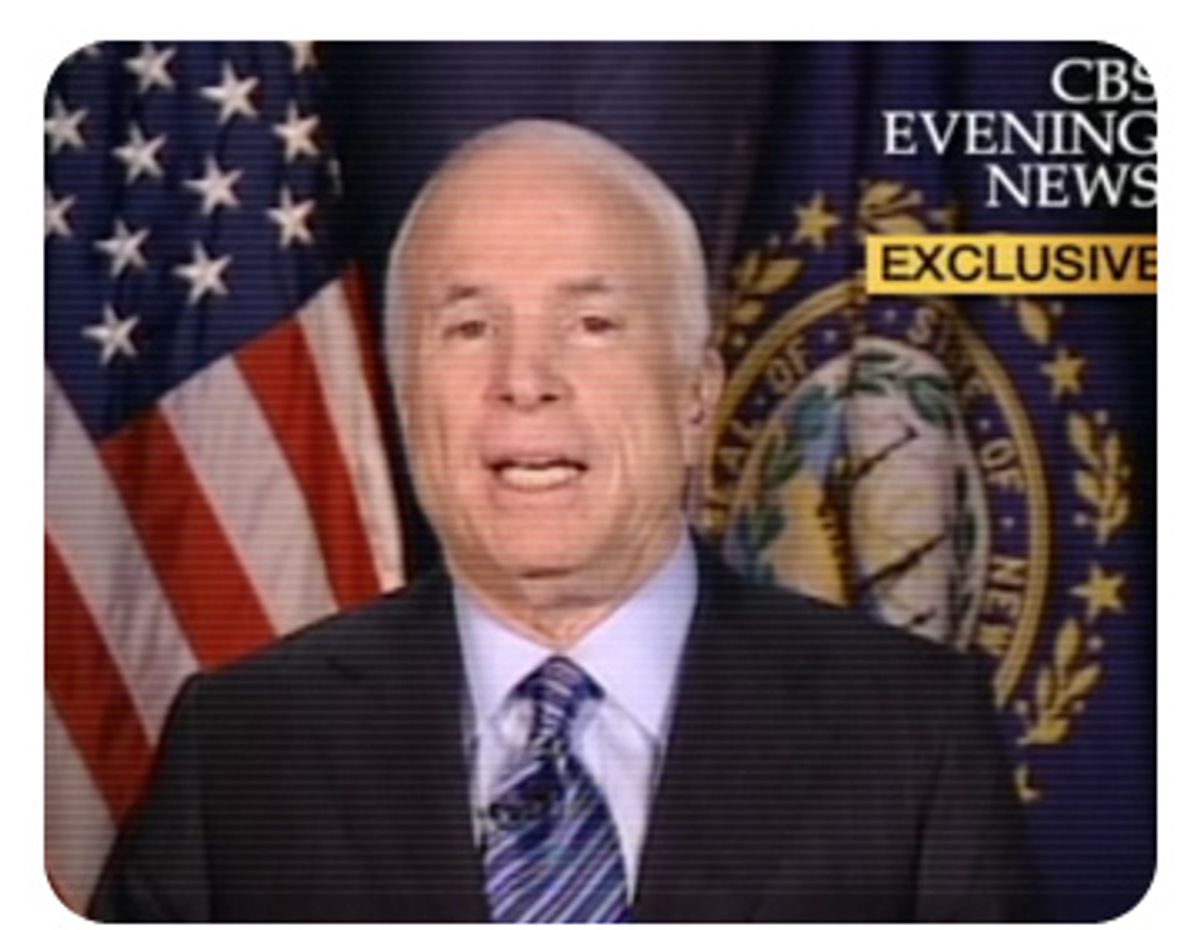

The rebuttals of McCain's embarrassing assertion that the Sunni insurgency's turn toward the U.S. and away from al-Qaida came because of the surge have been ample and devastating. His badly skewed sense of time and events has raised fresh doubts about his fitness for the presidency, since he was either incapable of comprehending contemporary facts or intentionally misleading the public when he told CBS anchor Katie Couric that the Anbar awakening "began" during the surge (and that troop escalation enabled the U.S. to protect a Sunni sheik who was actually assassinated during that period).

But aside from that moment of untruth, there are deeper problems in all the airy assertions about the triumph of the surge.

First there is the matter of that shift by the Sunni insurgents, which had nothing to do with the escalation. What changed the minds of the Sunni rebels in Anbar province and elsewhere was a revamped counterinsurgency doctrine that emphasized careful bribery over indiscriminate reprisals -- and that seized upon the growing alienation of the Sunnis from the bullying, murderous leadership of al-Qaida in Iraq. The American military officers who oversaw and implemented that strategy, including Gen. David Petraeus, deserve full credit. Even Petraeus, a strong supporter of the surge, makes very limited claims about its role in bolstering the Sunni turn, however.

In fact, it was the prospect of an early U.S. withdrawal, not the surge, that prompted the Sunni insurgents to change sides, according to the American officers who worked with their leaders. A fascinating article in the current issue of Foreign Affairs by Georgetown professor Colin Kahl and retired Gen. William Odom quotes Marine Maj. Gen. John Allen, who ran the tribal engagement operations in Anbar during 2007, saying that the Democratic sweep in the 2006 midterm elections and the increasing demand for withdrawal by the American public "did not go unnoticed" among the province's Sunni sheiks. "They talked about it all the time." Allen also told Kahl that the Marines exploited those concerns by telling the sheiks: "We are leaving ... We don't know when we are leaving, but we don't have much time, so you [the Anbaris] better get after this." Kahl and Odom write that "the risk that U.S. forces would leave pushed the Sunnis to cut a deal to protect their interests while they still could." They also quote Maj. Niel Smith, the operations officer at the U.S. Army and Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Center, and Col. Sean MacFarland, commander of U.S. forces in Ramadi during that crucial period, who wrote a long article on the Anbar awakening in the journal Military Review. "A growing concern that the U.S. would leave Iraq and leave the Sunnis defenseless against Al-Qaeda and Iranian-supported militias," they recalled, "made these younger [tribal] leaders [who led the awakening] open to our overtures."

There is no doubt that the surge has coincided with diminishing violence in Iraq, although kidnappings and bombings continue daily. As many critics have pointed out, surge proponents always compare the present period with the worst months of 2006 and 2007 -- and the arrival of 30,000 troops is not necessarily why the killing has ebbed.

Perhaps the most plausible reason is that there are many fewer Iraqis to kill in the places where the worst violence occurred, because so many of them have abandoned their homes or left the country altogether. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that roughly 5 million Iraqis have fled, with nearly half of them now living in Syria, Jordan or other neighboring states. Others belong to the cohort known as the "internally displaced," who have sought refuge from the militias "cleansing" Baghdad in either the northern or southern provinces. When there isn't anybody left to kill, the murder statistics tend to improve.

Another fortunate coincidence was the decision of Muqtada al-Sadr, the rebel Shiite leader, to order his militia leaders to stand down in August 2007, just as the surge troops were arriving. That cease-fire broke down last spring in southern Iraq but was then reinstated, in part at the instigation of Iran and in part because of Sadr's own political ambitions.

Why conditions became better in Iraq is a crucial issue not only because it may affect the outcome of the U.S. presidential election but, more important, because it indicates the best way out. For McCain and Bush, proving the success of the surge is important because that means the occupation must continue. For the overwhelming majority of Americans, including Barack Obama, that is an unsustainable option.

What we should learn from the history of the surge is that only the prod of withdrawal, rather than indefinite escalation, can persuade the Iraqis to defend themselves as a sovereign state.

Shares