Earlier this month, the folks at MoveOn.org came to me with a challenge: Study the history of Congress' efforts to halt, or at least halt the escalation of, the Vietnam War, and mine it for lessons about what Congress should do about Iraq now. They found themselves saddled with a historian deeply suspicious of using history to glibly draw battle plans for the present -- but one who emerged, nonetheless, believing that this time the lessons are clear. Last Thursday, Salon ran Walter Shapiro's article "Why the Democrats Can't Stop the Surge." I've come to a different conclusion about what Congress can or can't do. The questions are not just: Can Congress stop the surge? Can Congress stop a war-mongering president in his tracks? The better question is what are the things Congress can accomplish just by trying to stop the escalation, boldly, and without apology?

The answer to that is: an enormous amount -- and that the only thing that can guarantee Democratic political weakness in 2008 is if they abandon a strong withdrawal (or, if you prefer, "redeployment") position.

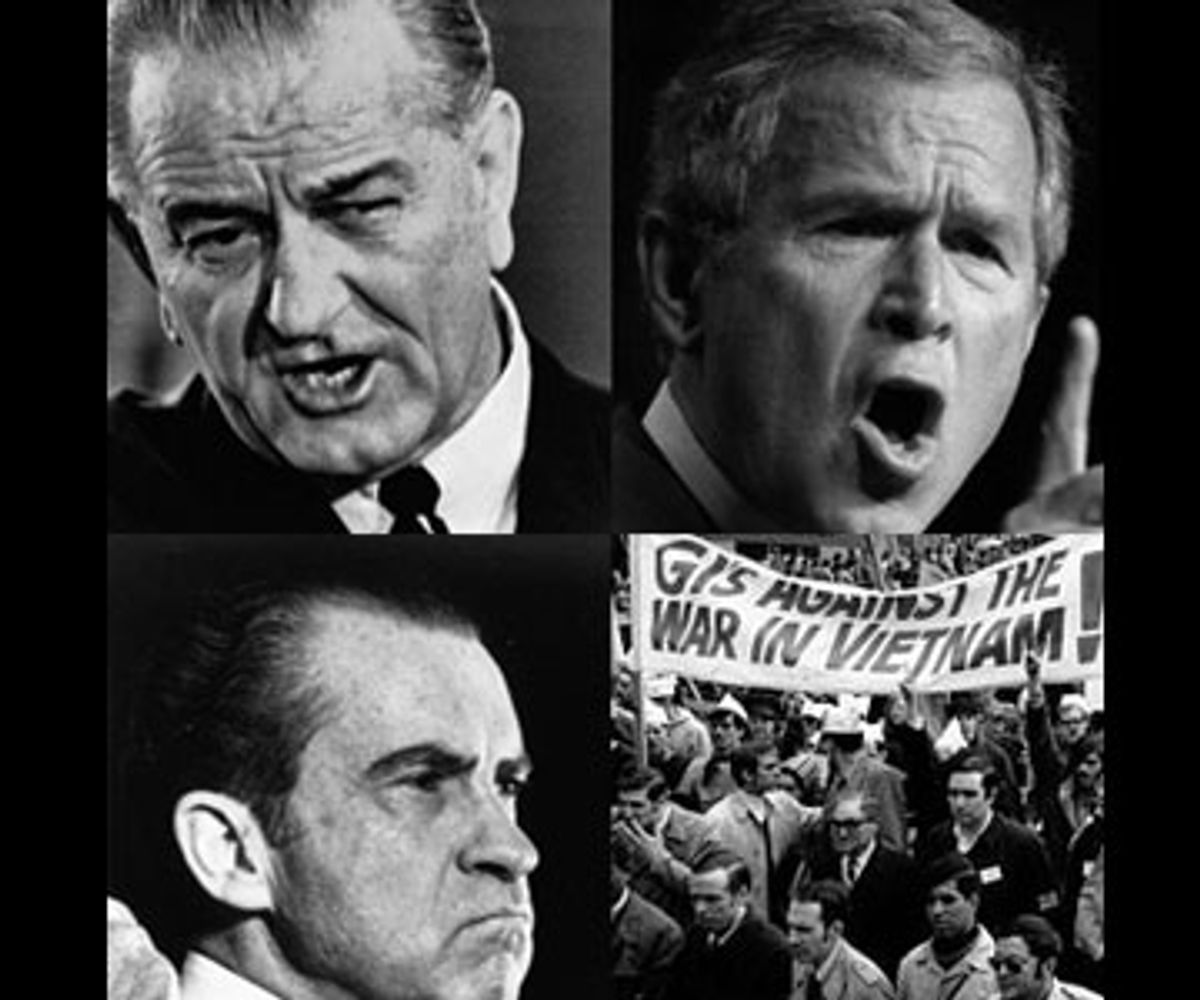

Let's start at the very beginning. Representatives and senators had been criticizing the creep, creep, creep of America's escalating military involvement in Indochina at least since 1963. The hammer really started coming down, though, in February 1966 -- when, a year after Lyndon Johnson began the first bombing runs over North Vietnam, Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman J. William Fulbright of Arkansas called hearings questioning the entire underlying logic of the war. Americans had been doing that in the streets for some time by then. Shortly after the Senate passed the president's 1965 $700 million military appropriation for Vietnam 88 to 3, the antiwar movement staged its first big Washington demonstration -- with about 20,000 young people on the Mall. But the collective reaction of the guardians of polite opinion was a sneer. "Holiday From Exams," the New York Times headed its dispatch.

By contrast, when Sen. Fulbright began his hearings, they stood up and took notice. All three networks covered the hearings live over six days. Thus did Americans learn from hippies like World War II hero Gen. James Gavin and George Kennan, architect of the Cold War doctrine of "containment" -- who said, "If we were not already involved as we are today in Vietnam, I would know of no reason why we should wish to become so involved, and I could think of several reasons why we should wish not to," and that victory could come only "at the cost of a degree of damage to civilian life and civilian suffering ... for which I would not like to see this country responsible."

President Johnson did not sit by idly. He directed the FBI to monitor the proceedings to find where they were echoing the so-called Communist line -- and had agents study wiretaps of the Soviet Embassy for evidence of friendly congressional contact. He also may have had words with the top network brass. CBS, for one, cut away from Kennan's testimony to return to regularly scheduled programming ("I Love Lucy" and "Andy Griffith Show" reruns). The execs defended themselves, claiming the hearings served to "obfuscate" and "confuse" the issues.

First lesson: Forthright questioning of a mistaken war by prominent legislators can utterly transform the public debate, pushing it in directions no one thought it was prepared to go.

Second lesson: Congress horning in on war powers scares the bejesus out of presidents.

The FBI was the least of it. The political threats were even worse. The next year, when Fulbright told the president at a meeting with the Senate leadership that the war was "ruining our domestic and our foreign policy," the president's response was a dare: Repeal the Gulf of Tonkin resolution -- the authorization of force that passed 98 to 2 in 1964. "You can tell the troops to come home" -- put up or shut up. What's more, "You can tell General Westmoreland that he doesn't know what he's doing." This was the same sword of Damocles that potential congressional anti-surgers feel swinging over their heads now: Any second-guessing of the chain of command, and I, the president, will blame everything bad that happens on you. It set a pattern for presidential push-backs against legislators' assertion of their constitutional oversight power. Nixon was even worse.

In March 1968, campaigning in the Republican primary in New Hampshire, the man who would become the next president of the United States laid down his marker on Vietnam: "If in November this war is not over, I say that the American people will be justified in electing new leadership, and I pledge to you that new leadership will end the war and win the peace in the Pacific." It was reported as if a campaign promise: A President Nixon would end the war. Nixon spent the rest of the campaign season refusing to say any more about what he meant -- claiming that to do so would jeopardize President Johnson's negotiations with the enemy.

At Nixon's first press conference in 1969, Helen Thomas, blunt as ever, asked him, "Now that you are president, what is your peace plan for Vietnam?" His desultory answer only repeated proposals already on the table. In reality he had no "peace plan" -- save for the fantasy that he could bomb the enemy so savagely that it would surrender at the negotiating table. The falseness of the presumption that the president intended to end the war expeditiously was revealed to George McGovern, the most forceful Senate dove, in an early meeting with Henry Kissinger. Why, McGovern asked the president's national security advisor, didn't Nixon just announce that while his predecessors Kennedy and Johnson had committed troops in good faith, subsequent events had shown that the commitment was no longer in the nation's interest? Kissinger responded by agreeing with the premise -- that the war was a mistake -- but nonetheless assuring him they had no intention of withdrawing short of victory.

In March, McGovern shocked even his fellow doves by saying on the Senate floor that "the only acceptable objective now is an immediate end to the killing." Sen. Edward M. Kennedy called his words "precipitate." The president had recently been asked at a press conference if he "could keep American public opinion in line if this war were to go on months and even years." He responded, "Well, I trust that I am not confronted with that problem, when you speak of years." The New York Times reported, "Public pressure over the war has almost disappeared." Those were the rules of the game: The president said he was ending the war. We had to trust him to do what he promised.

Of course, shortly thereafter, it was revealed that the president was secretly bombing neutral Cambodia. Shortly after that the public mind was blown by reports of the butchery of the battle at "Hamburger Hill," in which 46 Americans died in a day -- the kind of thing Americans trusted the president had put in the past. Nixon calmed things down by beginning a regular series of addresses in which he announced ever greater withdrawals of troops from Vietnam. On April 20, 1970, he made his most dramatic one yet: "The decision I announce tonight means that we finally have in sight the just peace we are seeking." The war, he seemed to be promising, was all but over.

Ten days later he went back on TV and staggered the nation by announcing he was invading neutral Cambodia.

Another lesson: Presidents, arrogant men, lie. And yet the media, loath to undermine the authority of the commander in chief, trusts them. Today's congressional war critics have to be ready for that. They have to do what Congress immediately did next, in 1970: It grasped the nettle, at the president's moment of maximum vulnerability, and turned public opinion radically against the war, and threw the president far, far back on his heels.

Immediately after the Cambodian invasion Senate doves rolled out three coordinated bills. (Each had bipartisan sponsorship; those were different days.) John Sherman Cooper, R-Ken., and Frank Church, D-Idaho, proposed banning funds for extending the war into Cambodia and Laos. Another bipartisan coalition drafted a repeal of the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, the congressional authorization for war that had passed 98 to 2 in 1964. George McGovern, D-S.D., and Mark Hatfield, R-Ore., were in charge of the granddaddy of them all: an amendment requiring the president to either go to Congress for a declaration of war or end the war, by Dec. 31, 1970. Walter Shapiro wrote that a "skittish" Congress made sure its antiwar legislation had "loopholes" to permit the president to take action to protect U.S. troops in the field" -- which means no genuine congressional exit mandate at all. But McGovern-Hatfield had no such "loopholes." (Of course, McGovern Hatfield didn't pass, and thus wasn't subject to the arduous political negotiating process that might have added them.) It was four sentences long, and said: Without a declaration of war, Congress would appropriate no money for Vietnam other than "to pay costs relating to the withdrawal of all U.S. forces, to the termination of United States military operations ... to the arrangement for exchanges of prisoners of war," and to "food and other non-military supplies and services" for the Vietnamese.

Radical stuff. Far more radical than today's timid congressional critics are interested in going. But what today's timid congressmen must understand is that the dare paid off handsomely. With McGovern-Hatfield holding down the left flank, the moderate-seeming Cooper-Church passed out of the Foreign Relations Committee almost immediately. Was the president on the defensive? And how. His people rushed out a substitute "to make clear that the Senate wants us out of Cambodia as soon as possible." Two of the most hawkish and powerful Southern Democrats, Fritz Hollings and Eugene Talmadge, announced they were sick of handing blank checks to the president. A tide had turned, decisively. By the time Cooper-Church passed the Senate overwhelmingly on June 30, the troops were gone from Cambodia -- an experiment in expanding the war that the president didn't dare repeat. Congress stopped that surge. It did it by striking fast -- and hard -- when the iron was hottest. In so doing, it moved the ball of public opinion very far down the field. By August, a strong plurality of Americans supported the McGovern-Hatfield "end the war" bill, 44 to 35 percent.

There is, here, another crucial lesson for today: Grass-roots activism works. The Democratic presidential front-runner back then, Sen. Edmund Muskie of Maine, afraid of being branded a radical, had originally proposed instead a nonbinding sense-of-the-Senate resolution recommending "effort" toward the withdrawal of American forces within 18 months. He found himself caught up in a swarm: the greatest popular lobbying campaign ever. Haverford College, which was not atypical, saw 90 percent of its student body and 57 percent of its faculty come to Washington to demonstrate for McGovern-Hatfield. A half-hour TV special in which congressmen argued for the bill was underwritten by 60,000 separate 50-cent contributions. The proposal received the largest volume of mail in Senate history. Muskie withdrew his own bill, and became the 19th cosponsor of McGovern-Hatfield.

Muskie's sense-of-the-Senate resolution was the wrong thing to do -- just as Democratic Sens. Carl Levin and Joe Biden's sense-of-the-Senate resolution, cosponsored with Republican Chuck Hagel, is the wrong thing to do. Congressional doves, by uniting around a strong offensive -- eschewing triangulation -- weakened the president. McGovern-Hatfield did not pass in 1970. But the campaign for it helped make 1971 President Nixon's worst political year (until, that is, Congress' bold action starting in 1973 to investigate Watergate). By that January, 73 percent of Americans supported the reintroduced McGovern-Hatfield amendment. John Stennis, D-Miss., Nixon's most important congressional supporter, now announced he "totally rejected the concept ... that the President has certain powers as Commander in Chief which enable him to extensively commit major forces to combat without Congressional consent." In April the six leading Democratic presidential contenders went on TV and, one by one, called for the president to set a date for withdrawal. (One of them, future neoconservative hero Sen. Henry "Scoop" Jackson, differed only in that he said Nixon should not announce the date publicly.)

This was a marvelous offensive move: It threw the responsibility for the war where the commander in chief claimed it belonged -- with himself -- and framed subsequent congressional attempts to set a date a reaction to presidential inaction and the carnage it brought. When the second McGovern-Hatfield amendment went down 55-42 in June, it once more established a left flank -- allowing Majority Leader Mike Mansfield to pass a softer amendment to require withdrawal nine months after all American prisoners of war were released. Senate doves, having dared the fight, were doing quite well in this game of inches.

Which brings us back to lesson two, above. Richard Nixon was terrified. He reached into Lyndon Johnson's bag of tricks, calling Mansfield into the White House and reminding him that he was in the middle of negotiations on the war and on arms control. He said that if they collapsed he would go on TV, too -- and blame Mansfield personally. He called in House Majority leader Carl Albert and said that if the similar resolution pending in the House succeeded he would simply scuttle the Vietnam negotiations, and blame Albert personally. The resolution lost by 23 votes.

Failure, just as Walter Shapiro says? I see a glass half full -- and a strategy congressional Democrats should emulate now. The bedrock reason is the election. The election in 1972, I mean; and the election in 2008.

It sounds crazy to say it, because anyone who knows anything knows that the 1972 election was a world-historic failure for the Democrats because McGovern lost 49 states. Put aside, for now, the story of that crushing defeat. (It is a story of the most tragically inappropriate presidential nominee in history, and the unprecedentedly dirty campaign against him -- the substance of Watergate.) What that colossal distraction distracts us from is that congressional doves, and Congressional Democrats, performed outstandingly in that election. Democrats gained a seat in the Senate, the McGovern coattails proving an irrelevancy. America simultaneously rejected George McGovern and voted for McGovernism: Democrats who voted twice for his amendment to demand a date certain to end the Vietnam War did extremely well. Nixon knew his fantasy of expanding the air war unto victory was over. In fact, those who saw him the morning after the election said they'd never seen him so depressed. Why? "We lost in the Senate," he told one mournfully. He lost his mandate to make war as he wished.

We can likewise expect a similarly nasty presidential campaign against whomever the Democrats nominate in 2008. But we can also assume that he or she won't be as naive and unqualified to win as McGovern; one hopes the days in which liberals fantasized that the electorate would react to the meanness of Republicans by reflexively embracing the nicest Democrat are well and truly past. What we also should anticipate, as well, is the possibility that the Republicans will run as Nixon did in 1968 and 1972: as the more trustworthy guarantor of peace. Ten days before the 1972 election, Henry Kissinger went on TV to announce, "It is obvious that a war that has been raging for 10 years is drawing to a conclusion ... We believe peace is at hand." McGovern-Hatfield having ultimately failed twice, its supporters were never able to claim credit for ending the war. That ceded the ground to Nixon, who was able to claim the credit for himself instead. He never would have been able to do that if he had been forced to veto legislation to end the war.

McGovern-Hatfield failed because of presidential intimidation, in the face of overwhelming public support. Nixon and Nixon surrogates pinioned legislators inclined to vote for it with the same old threats. A surviving document recording the talking points had them say they would be giving "aid and comfort" to an enemy seeking to "kill more Americans," and, yes, "stab our men in the back," and "must assume responsibility for all subsequent deaths" if they succeeded in "tying the president's hands through a Congressional Appropriations route."

But isn't that interesting: There wouldn't have been subsequent deaths if they had had the fortitude to stand up to the threats.

Every time congressional war critics made Congress the bulwark of opposition to a war-mongering president, they galvanized public opinion against the war. The same thing seems to be happening now. Already, the guardians of respectable opinion are sneering less; there are simply too many anti-surge bills on the table for that. The shame would be if today's only credible antiwar party, the Democrats, squander that opportunity by failing to harness their majority, not merely for a strong showing against escalation but in favor of a position to credibly end the war.

You know that whatever the facts, the right will blame "liberals" and "Democrats" for losing Iraq; that's as inevitable as the fact that we've already lost Iraq -- and as inevitable as an arrogant president playing into Democratic hands by expanding the engagement (he already is). What would be inexcusable is if wobbly Democrats managed to maneuver themselves timidly into a corner that made them only the right-wing's scapegoats -- and not the champions that truly made their stand to end the war.

In 2008, the Republicans are going to have to run either amidst an electorate convinced that Republicans will be staying the course or amidst an electorate they've managed to bamboozle into believing "peace is at hand." If they manage the latter, they'll have a good chance of winning the election. But the only way they can do that is if Democrats can't claim credit for ending it first. I hope to be able to watch the Democrats truly try to end the war; it will be glorious. Because even if they start losing votes in Congress, the president and the party that enables him can only become politically weaker by the day.

Shares