Each year of George W. Bush's war in Iraq has been represented by a thematic falsehood. That Iraq is now calm or more stable is only the latest in a series of such whoppers, which the mainstream press eagerly repeats. The fifth anniversary of Bush's invasion of Iraq will be the last he presides over. Sen. John McCain, in turn, has now taken to dangling the bait of total victory before the American public, and some opinion polls suggest that Americans are swallowing it, hook, line and sinker.

The most famous falsehoods connected to the war were those deployed by the president and his close advisors to justify the invasion. But each of the subsequent years since U.S. troops barreled toward Baghdad in March 2003 has been marked by propaganda campaigns just as mendacious. Here are five big lies from the Bush administration that have shaped perceptions of the Iraq war.

Year 1's big lie was that the rising violence in Iraq was nothing out of the ordinary. The social turmoil kicked off by the invasion was repeatedly denied by Bush officials. When Iraqis massively looted government ministries and even private shops, then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld joked that U.S. media had videotape of one man carrying off a vase and that they kept looping it over and over again. The first year of the war saw the rise of a Sunni Arab guerrilla movement that repeatedly struck at U.S. troops and at members and leaders of the Shiite-dominated Interim Governing Council appointed by the American government.

After dozens of U.S. and British military deaths, Rumsfeld actually came out before the cameras and denied, in July of 2003, that there was a building guerrilla war. When CNN's Jamie McIntyre quoted to him the Department of Defense definition of a guerrilla war -- "military and paramilitary operations conducted in enemy-held or hostile territory by an irregular predominantly indigenous forces" -- and said it appeared to fit Iraq, Rumsfeld replied, "It really doesn't." Bush was so little concerned by the challenge of an insurgency that he cavalierly taunted the Sunni Arab guerrillas, "Bring 'em on!" regardless of whether it might recklessly endanger U.S. soldiers. The guerrillas brought it on.

In Year 2 the falsehood was that Iraq was becoming a shining model of democracy under America's caring ministrations. In actuality, Bush had planned to impose on Iraq what he called "caucus-based" elections, in which the electorate would be restricted to the provincial and some municipal council members backed by Bush-related institutions. That plan was thwarted by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, who demanded one-person, one-vote open elections, and brought tens of thousands of protesters out onto the streets of Baghdad and Basra.

The elections were deeply flawed, both with regard to execution and outcome. The U.S. campaign against Fallujah in November 2004, marked by more petulant rhetoric from Bush, had angered Sunni Arabs -- who feared U.S. strategy favored Shiite ascendancy -- and led to their boycotting the elections. The electoral system chosen by the United Nations and the U.S. would guarantee that if they boycotted, they would be without representation in parliament. Candidates could not campaign, and voters did not know for which individuals they were voting.

Much of the American public, egged on by White House propaganda, was sanguine when elections were held at the end of January 2005, mistaking process for substance. Why the disenfranchisement of the Sunni Arabs, who were becoming more and more violent, was a good thing, or why the victory of Shiite fundamentalists tied to Iran was a triumph for the U.S., remains difficult to discern. Nobody in the Middle East thought such flawed elections, held under foreign military occupation, were any sort of model for the region.

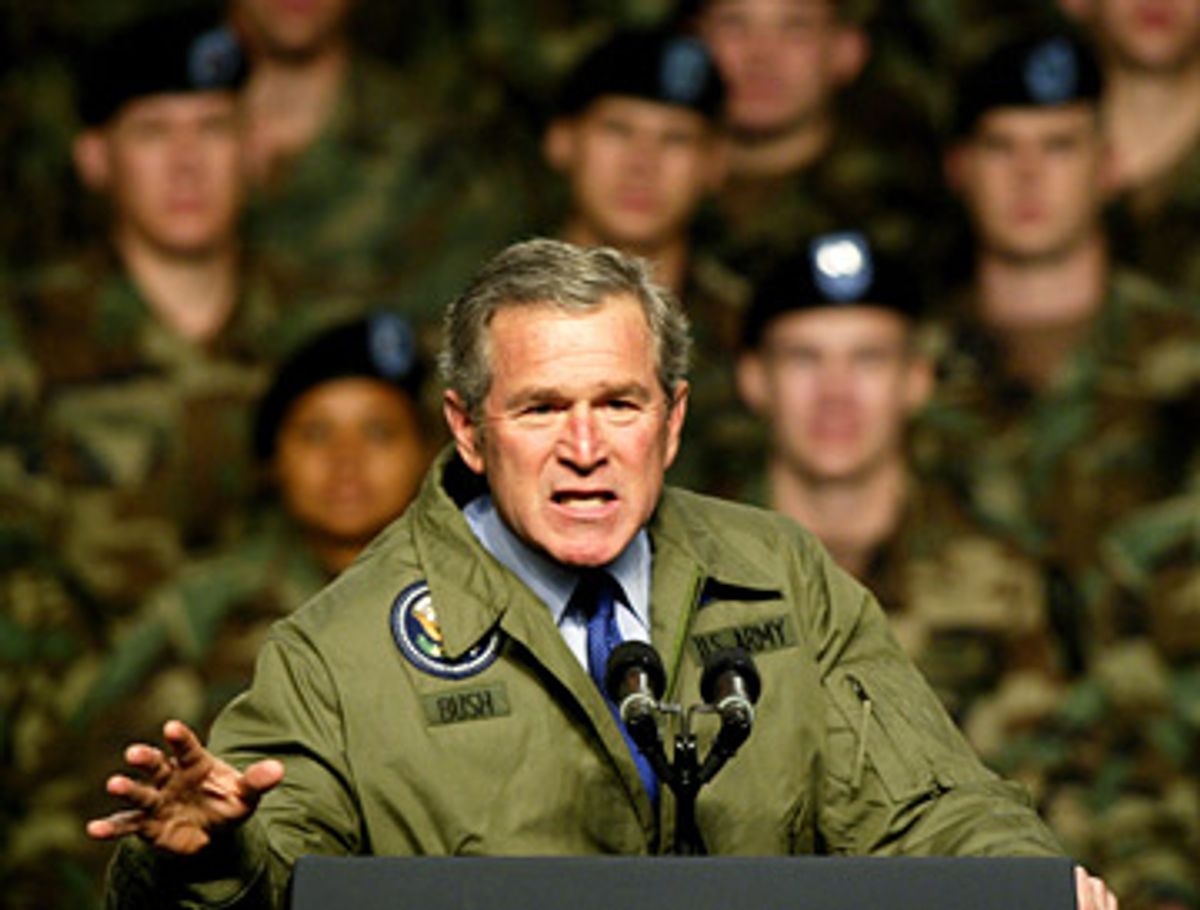

In Year 3, the Bush administration blamed almost everything that was going wrong on one shadowy figure: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Bush set the tone for Year 3 with a speech at Fort Bragg on July 28, 2005, in which he said, "The only way our enemies can succeed is if we forget the lessons of September 11 ... if we abandon the Iraqi people to men like Zarqawi .. and if we yield the future of the Middle East to men like bin Laden." The previous week, Bush had said that the U.S. was in Iraq "because we were attacked." Zarqawi was the perfect plot device for an administration who wanted to perpetuate the falsehood that the Iraq war was directly connected with Sept. 11 and al-Qaida.

In spring of 2006, Maj. Gen. Rick Lynch came out and attributed 90 percent of suicide bombings in Iraq to Zarqawi and his organization, which he had rebranded as "al-Qaida in Iraq," but which had begun in Afghanistan as an alternative to Osama bin Laden's terrorist organization. Meanwhile, security analysts discerned 50 distinct Sunni Arab guerrilla cells in Iraq. Some were Baathists and some were Arab nationalists; some were Salafi Sunni fundamentalists while others were tribally based. To attribute so many attacks all over central, western and northern Iraq to a single entity suggested an enormous, centrally directed organization in Iraq called "al-Qaida." But there was never any evidence for such a conclusion, and when Zarqawi was killed by a U.S. airstrike in May of 2006, the insurgent violence continued without any change in pattern.

In Year 4, as major sectors of Iraq descended into hell, Bush's big lie consisted of denying that the country had fallen into civil war. In late February 2006, Sunni guerrillas blew up the golden-domed Askariya shrine of the Shiites in Samarra. In the aftermath, the Shiites, who had shown some restraint until that point, targeted the Sunni Arabs in Baghdad and its hinterlands for ethnic cleansing. After May 2006, the death toll of victims of sectarian violence rose at times to an official figure of 2,500 or more per month, and it fluctuated around that level for the subsequent year. The Baghdad police had to form a new unit, the Corpse Patrol, to collect dozens of bodies every morning in the streets of the capital.

On Sept. 1, 2006, Sunni guerrillas slaughtered 34 Asian and Iraqi Shiite pilgrims passing near Ramadi on their way to the Shiite holy city of Karbala south of Baghdad. In his weekly radio address the next day Bush said, "Our commanders and diplomats on the ground believe that Iraq has not descended into a civil war." Many lesser conflicts have been dubbed civil wars by journalists, academics and policy thinkers alike. But Bush continued with the fantastic spin: "The people of Baghdad are seeing their security forces in the streets, dealing a blow to criminals and terrorists."

Year 5, the past year, has been one of troop escalation, or the "surge." (Calling the policy a "surge" rather than an "escalation" is emblematic of the administration's propaganda.) The big lie is that Iraq is now calm, that the surge has worked, and that victory is within reach.

In early 2007, the U.S. made several risky bargains. It pledged to the Shiite government of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki that it would disarm the Sunni Arab guerrillas in Baghdad first, before demanding that the Shiites lay down their arms. It thus induced Muqtada al-Sadr to declare a freeze on the paramilitary activities of his Mahdi army militia. The Americans would go on to destroy some of his Sunni Arab enemies for him. U.S. military leaders in Iraq began paying Sunni Arab Iraqi guerrillas and others in provinces such as al-Anbar to side with the United States and to turn on the foreign jihadis, most of them from Saudi Arabia and North Africa. U.S. troops also began a new counterinsurgency strategy, focused on taking control of Sunni Arab neighborhoods, clearing them of armed guerrillas, and then staying in them on patrol to ensure that the guerrillas did not reestablish themselves.

The strategy of disarming the Sunni Arabs of Baghdad -- who in 2003 constituted nearly half the capital's inhabitants -- had enormous consequences. Shiite militias took advantage of the Sunnis' helplessness to invade their neighborhoods at night, kill some as an object lesson, and chase the Sunnis out. Hundreds of thousands of Baghdad residents were ethnically cleansed in the course of 2007, during the surge, and some two-thirds of the more than 1.2 million Iraqi refugees who ended up in Syria were Sunni Arabs. Baghdad, a symbol of past Arab glory and of the Iraqi nation, became at least 75 percent Shiite, perhaps more.

That outcome has set the stage for further Sunni-Shiite conflict to come. Much of the reduction in the civilian death toll is explained by this simple equation: A formerly mixed neighborhood like Shaab, east of the capital, now has no Sunnis to speak of, and so therefore there are no longer Sunni bodies in the street each morning.

But the troop escalation has failed to stop bombings in Baghdad, and the frequency and deadliness of attacks increased in February and March, after falling in January. In the first 10 days of March, official figures showed 39 deaths a day from political violence, up from 29 a day in February, and 20 in January. Assassinations, attacks on police, and bombings continue in Sunni Arab cities such as Baquba, Samarra and Mosul, as well as in Kirkuk and its hinterlands in the north. On Monday, a horrific bombing in the Shiite shrine city of Karbala killed 52 and wounded 75, ruining the timing of Vice President Cheney's and Sen. McCain's visit to Iraq to further declare victory.

Moreover, Turkey made a major incursion into Iraq to punish the guerrillas of the Kurdish Workers Party from eastern Anatolia, who have in the past seven months killed dozens of Turkish troops. The U.S. media was speaking of "calm" and "a lull" in Iraq violence even while destructive bombs were going off in Baghdad, and Turkey's incursion was resulting in over a hundred deaths. The surge was "succeeding," according to the administration, and therefore no mere attacks by a third country, or bombings by insurgents, could challenge the White House story line.

Bush's five big lies about Iraq powerfully shaped press coverage of the war and have kept the mess there going at least long enough to turn it over to the next president. As he campaigns for the White House, John McCain, Bush's heir apparent in the Iraq propaganda department, has been signaling that "complete victory" in Iraq will be his talking point of choice for Year 6. If the mainstream media and the American public don't wake up to the truth about how the war has gone, they'll find themselves buying into an even longer and deeper tragedy.

Shares