David Mamet's new children's book, "Henrietta," gave me an anxiety attack.

This wasn't the response I'd expected to have. I've never seen a David Mamet play, but his movies and essays always leave a fine, sharp taste in my mouth -- as if I've been admitted into some leathery gentlemen's club for an evening and left with smoke in my lungs but a firmer grasp of the male soul. Mamet, like Hemingway and other old-school newspaper sorts -- with their rat-a-tat phrasing and liberal, almost poetic use of epithets -- proves that literary material need not be verbose or ponderous to be smart. Mamet makes me laugh, but it's not a brainless cackle; instead, I feel wise.

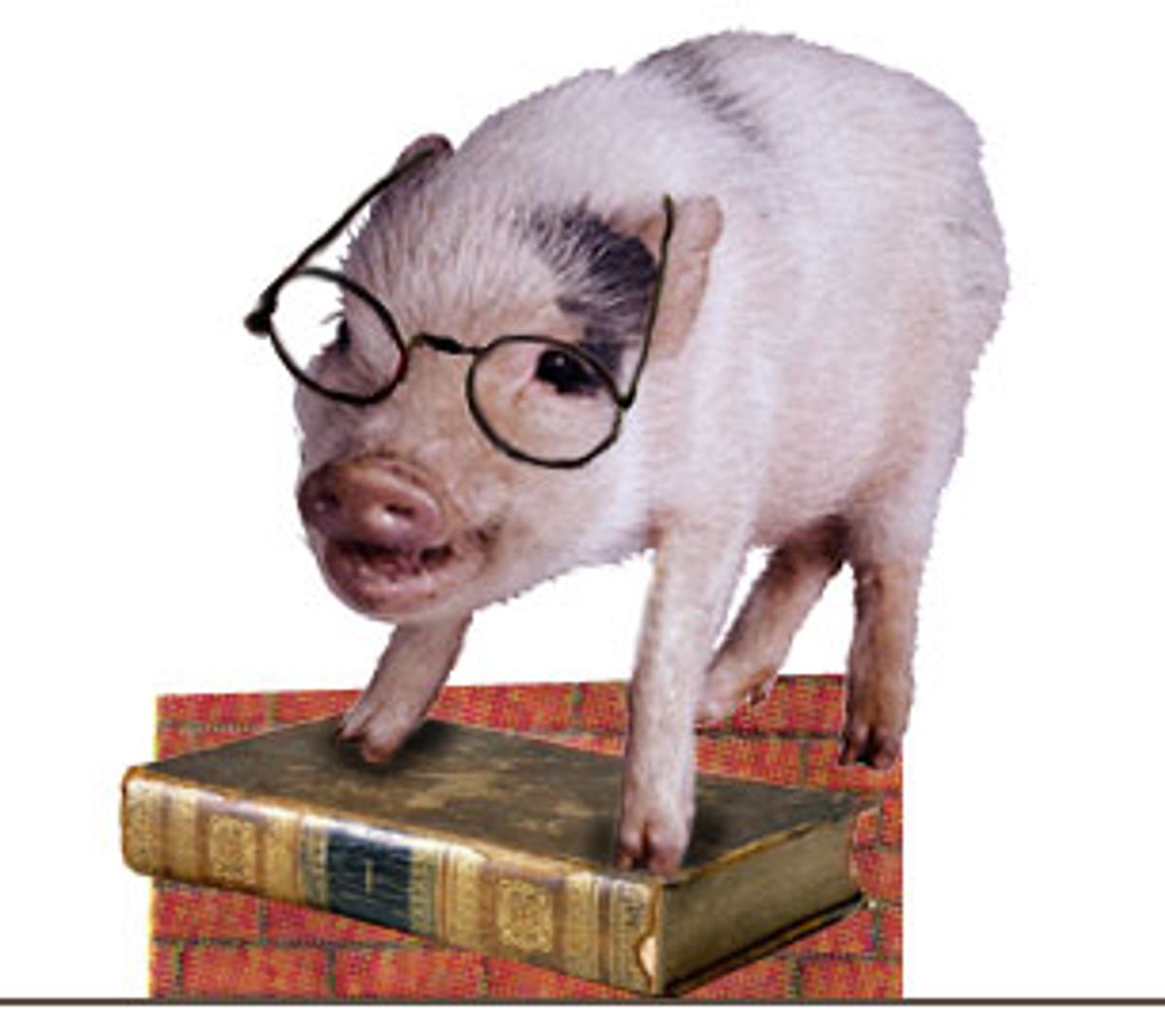

But this tale of a self-educated pig who strives to attend an institution that looks very much like Harvard Law School didn't make me laugh or feel wise. It made me feel nervous. Had I missed the allegory?

I suspect there is some complex philosophical premise at work beneath the tale's apparent wry simplicity. Perhaps it's Talmudic; I know Mamet has gotten very into his Judaism of late. I pictured adults chuckling knowingly while their savvy, Ivy-destined kiddies admired the pictures of the clever animal, who is "brought to life by Elizabeth Dahlie's heartwarming illustrations."

Though "heartwarming" is not the adjective I would have picked, Dahlie's watercolor illustrations of the pig are sweet: She gives Henrietta a beribboned tail, and ears that droop when she is thwarted. Mamet's language here is clean: free of the F-word, with only the occasional dash of his trademark-riddled syntax. (I wonder if the Harvard Coop will stock the $16 book alongside the pricey crimson rah-rah merchandise?)

The plot advances with merciful swiftness. Henrietta is a smart, anthropomorphic oinker who, after schooling herself in solitude on an anonymous East Coast isle, "burns to serve through the Medium of the Law." Sadly, she is rebuffed by the admissions office of the presumed Harvard. (The school itself is never named, but Henrietta dons a crimson-striped muffler and strolls past quasi-fictional landmarks like "Charles Square," and Alan Dershowitz offers a blurb.) Not that this stops her in her quest for knowledge; instead, she "haunted the libraries and folded herself into the backs of the lecture halls."

Of course, the bums kick her out. They even post signs: "No Pigs." (For me, this conjured up a vague memory of Snoopy in some long-forgotten Peanuts cartoon.)

Anyhoo, Henrietta descends into vagrancy -- a common enough condition in Harvard Square, where well-dressed suburban slacker teenagers regularly panhandle along with genuine destitutes -- until a myopic old vagabond proves to be her salvation. I won't give away how he saves her or who he proves to be. Let's just say it ends happily, with Henrietta delivering a noble commencement address worthy of any tweedy social-studies major.

"Let us not be sentimental over the accomplishments of one who comes from a disadvantaged group," she declares, "but let us work for social justice." And so she does, clawing -- or would it be scrabbling? -- her way up to the Supreme Court.

By the time Henrietta reaches the height of her career, "her accomplishments, of course, have been claimed by the School and the City," writes Mamet, a touch acidly, "but she continues to credit her family, her friends, her books, and her island."

What to make of this? Is Mamet railing against the historical resistance to minorities in Ivy League institutions, or against the dominance of the Ivy League in higher education at all? (For the record, Mamet himself went to Goddard College in Plainfield, Vt.) Is he saying that Harvard is a necessary evil, or that the true heroes are autodidacts who work toward a world where such evils become unnecessary? Or is it just a plug for good old-fashioned liberalism in the form of kindness to the downtrodden? Will this morality tale encourage the hyper-pressured children of the elite to ditch their private schools and Ritalin for home schooling?

God knows.

I'm not a parent. Nevertheless, I'm concerned that today's schoolchildren are getting parables of higher education written by intellectual heavyweights, rather than cozy narratives about children at play, like the charming Betsy-Tacy series I enjoyed in my youth.

I would be wary of giving any kid a book that even hints at the tortuous, exclusionary application process required for admission to top-flight colleges and law schools; they'll have plenty of time to enjoy that later. Maybe this book will serve as a palliative for a particularly sophisticated and anxious child, but for kids who have yet to lose sleep over their SAT scores, reading David Mamet will do nothing but add new monsters to the foot of the bed.

Frankly, I am afraid of David Mamet. Sure, he hides out in Vermont and designs silly hunting gear for Banana Republic. And he's easy to parody. (My boyfriend's sketch comedy troupe, the Associates, does a mean "Glengarry Glen Girl Scout.") But I still admire him greatly. So I read this thing several times through to try to do the pig justice, as it were.

It just left me shrugging.

My insecurity was heightened by the fact that I was asked to write this review in part because I am a Harvard graduate (though of the college, not the Law School). So if there were some underlying meaning, I would look all the more foolish for not picking up on it.

I am hyper-sensitive to the fact that the classroom portion of my Harvard education left me, essentially, an expert in nothing. Nor do I feel broadly educated. This was made clear to me during a red-faced Thanksgiving of a few years back, when a family friend expressed shock that I didn't recognize some obscure biblical reference. I can't even remember what the reference was; all I remember is the humiliation: "You went to Harvard and you don't even know -- ?"

"She's just jealous," my mother whispered later. The family friend's daughter had gone to some no-name school. But the incident still stung. She was right: I don't know anything.

Meanwhile, here we have this pig from some no-name island, whose breadth of knowledge -- Hamlet, Oedipus, Henry Fielding -- is certainly far greater than that of many Harvard literature graduates. It must mean something.

Shares