"Is it a rebellion?" the doomed king of France, Louis XVI, is supposed to have asked in 1789. "No, sire," a minister allegedly replied. "It is a revolution." The right-wing Tea Party movement in the United States in 2010 is not a revolution. It is a rebellion.

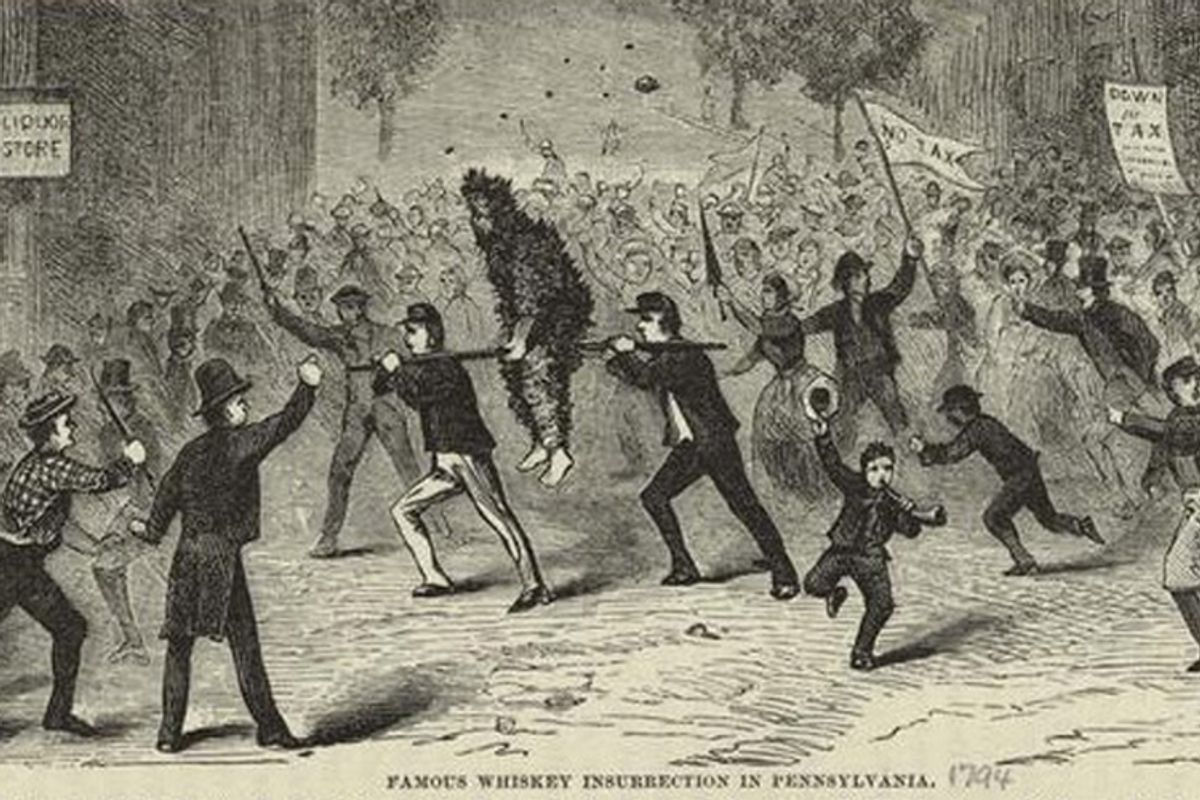

The movement chose the wrong historical precedent when it selected the Boston Tea Party of 1773, a genuinely revolutionary event, as its symbol. Today’s Tea Party movement is much more like the misguided and ill-fated Whiskey Rebellion of the early 1790s, during the first term of America’s first president, George Washington.

The Whiskey Rebellion originated as a protest against the plan that Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary of the United States, devised to pay down the federal and state debts that had been left over from the War of Independence. Hamilton proposed that the federal debt be funded at par -- that is, at face value, even though it was trading at only a fraction of that face value. And he proposed that the federal government assume and pay the outstanding debts of the states. These actions, Hamilton persuaded President Washington and Congress, would establish the new nation’s credit worthiness in the eyes of European creditors, making it less expensive for the federal and state governments to borrow money in the future.

From Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who was Hamilton’s rival in George Washington’s Cabinet, down through the many Democratic-Republican societies to the backwoods of Appalachia, critics of Hamilton’s plan denounced it as a giveaway to the Northeastern rich. Virginia and several other Southern states had paid their wartime debts and objected to being taxed to pay down the debts of other states. In addition, much of the debt had ended up in the hands of Northeastern speculators, whose agents had traveled through rural areas buying debt instruments at a fraction of their face value. Funding the debt at face value would provide these speculators with a huge windfall.

When Congress in 1791, at Hamilton’s suggestion, enacted an excise tax on whiskey, along with a tariff, to help pay down the consolidated national debt, the result was the Whiskey Rebellion. Resistance to federal tax collection by frontier settlers in Pennsylvania escalated until 1794, when hundreds of armed men attacked the home of a federal tax inspector. When Washington mobilized the militia, the insurrection collapsed, and the small number of rebels who were arrested were pardoned.

Today’s Tea Party movement resembles the Whiskey Rebellion -- but emphatically not because it is supported only by ignorant yahoos, as many critics of the Tea Partiers contend. On the contrary, just as the Tea Party is supported and subsidized by many elite conservatives, so the Whiskey Rebellion’s sympathizers included members of the early republic's elite, including Albert Gallatin, a Swiss immigrant who later became President Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of the Treasury. (The mature Gallatin adopted much of the Hamiltonian philosophy he had denounced in his youth and proposed a massive, federally funded canal and road system.)

Whether they are educated or not, the supporters of the Tea Party movement, like the supporters of the Whiskey Rebellion, are deeply confused. The Whiskey Rebels failed to understand that the federal funding of state debts almost certainly spared them much higher state taxes in the long run. Although the federal excise tax on whiskey was regressive, as a whole Hamilton’s scheme for funding the state debts was more progressive than debt payment schemes by the individual states would have been. For example, the state of Massachusetts alone had planned to pay its debt by raising more than $1 million a year in new taxes. In contrast, the interest on the consolidated national debt of $75.6 million required only $4.6 million from the entire United States. And whereas states repaying their debt would have relied heavily on highly regressive property taxes or poll taxes, the federal government raised revenue mainly from tariffs paid primarily by the affluent. While the rich disproportionately benefited from federal assumption of state debt, they also disproportionately paid the costs, sparing ordinary Americans the taxes that the states otherwise might have imposed. But the Whiskey Rebels were too busy grabbing their muskets to understand their own interests.

In the same way, the Tea Partiers who denounce the TARP and the 2009 stimulus fail to understand that the alternatives to those much-demonized policies would have been much worse. In a financial crisis, the government must rescue the financial system on which the rest of the economy depends. Progressives can plausibly argue that it would have been better to nationalize the banks, while recapitalizing them. But Tea Party conservatives who argue that the government should have allowed the national and global banking systems simply to collapse are, to be blunt, ignorant fools. And they are ignorant fools, too, when they argue that the 2009 stimulus was too large, when in fact it was too skewed toward tax cuts and too small to play its necessary role in boosting aggregate demand when consumer spending had cratered. The depth of their ignorant folly is demonstrated by the fact that most credible Republican conservative economists supported both the TARP and some sort of stimulus.

In another, even more important respect, the Tea Party resembles the Whiskey Rebellion rather than the Boston Tea Party. The Boston Tea Party was the beginning of a genuine popular revolution whose purpose was not to oppose government as such, but to transfer government from unelected rulers in Britain to elected representatives in the U.S. Once that transfer had taken place, the federal and state governments had the right to impose taxes, even stupid and counterproductive taxes, which Americans were free to protest against -- but only by means short of violence. George Washington was perfectly consistent in leading the revolution against illegitimate British authority and later taking to the saddle again, as president, to assert the legitimate authority of the federal government during the Whiskey Rebellion.

From the Whiskey Rebels to the Confederates to the Tea Party movement, there has been a minority tradition that viewed the American Revolution as a rebellion against government as such, rather than as a revolution on behalf of popular government. And from Thomas Jefferson to Newt Gingrich, crafty demagogues, when they are out of power, have portrayed the elected representatives of the American people as a tyrannical, alien force, only to exercise the full powers of the government without apology once they have successfully ridden paranoia to power.

Claims that the nation is about to be crushed by runaway debt have been part of the demagogic tradition, ever since Jefferson battled Hamilton while both served in the administration of Washington. Hamilton was confident that economic growth would permit the U.S. to pay down the consolidated federal and state debts that the anti-statists of his day found so horrifying. He told his friend and mentor, the financier Robert Morris: "Speaking within moderate bounds, our population will be doubled in thirty years; there will be a confluence of emigration from all parts of the world, our commerce will have a proportionate progress and of course our wealth and capacity for revenue. It will be a matter of choice if we are not out of debt in twenty years, without at all encumbering the people." History proved him right. The deficit hysterics of Hamilton’s day were wrong about the national debt then, and their demagogic, fear-mongering political descendants in the present day are just as wrong to suggest that debt is an imminent threat to the nation.

While pursuing negotiations with the Whiskey Rebels, President Washington put on his uniform and reviewed the troops assembled at Fort Cumberland, Md., in case they were needed. The violence of the Tea Party to date has been purely rhetorical. Its members will maul, not individual tax collectors, but the tax code, if the movement succeeds in sending even more intransigent reactionaries to the already paralyzed Congress and the Senate in this fall’s midterm elections.

They can gum up the works, but that is all they can do. Like the Whiskey Rebels of the 1970s, the misnamed Tea Partiers do not understand their own interests and have no plausible alternative program for the nation. They may pose as revolutionaries, but they are only a mob.

Shares