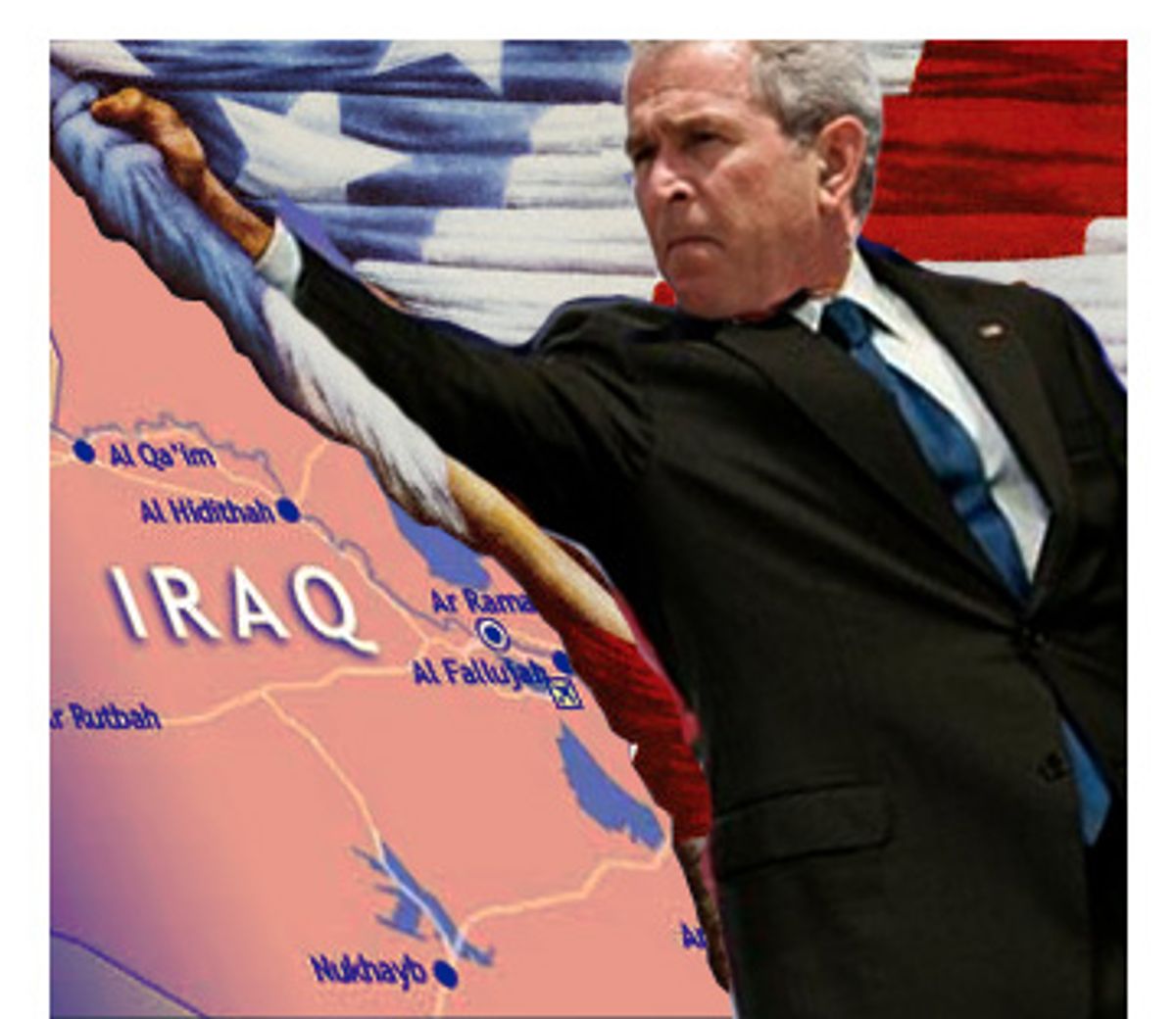

Bush's entire presidency has been propped up by the War Myth. By aggressively presenting himself as a war leader, by wrapping himself in the sacred robes of patriotism, the military and national honor, Bush has taken refuge in the holy of holies, the ultimate sanctuary in American life. He has made criticism of his policies tantamount to criticism of the one institution in American life that is untouchable: the military. He uses the almost 4,000 new crosses in military cemeteries as a talisman against his opponents -- notwithstanding the fact that he is wholly responsible for those crosses.

War may, as Randolph Bourne argued, be the health of the state, but it is definitely the health of the presidency. Paradoxically, the very thing that has destroyed Bush's presidency -- his disastrous war on Iraq -- is also the only thing that is propping it up. War is an incompetent leader's Waterloo -- but also his best friend. Being a "war president," as Bush incessantly calls himself, means never having to say you're sorry. No matter how many lives you have destroyed, you are not to blame.

What is crucial to understand is that the War Myth can be effective even when reality utterly undercuts it. Myths appeal to transcendental values, shared sacred beliefs. Once we have entered the realm of myth, taboos replace rational discourse.

That irrational power explains the Democrats' recent humiliating collapse on Bush's intelligence surveillance bill. It explains why Republican politicians, whose ideology is steeped in the War Myth, have failed to rebel against a doomed war that could cost them their jobs. And it is why the American political establishment is waiting hat in hand for Gen. Petraeus' predictable report, in which he will say the surge is working and ask for more time.

Bush's latest pro-war P.R. campaign is yet another attempt to tap into it. But the magic is finally wearing off. And in his desperation to save his presidency, Bush has been forced to squeeze the Myth so hard that its irrationality has become painfully evident.

Bush's invocation of the Vietnam War was a strangely convoluted and halfhearted attempt to reintroduce one of the most venerable War Myth themes: the "stab in the back." Last week, in a speech to a Veterans of Foreign Wars group in Kansas City, Mo. -- which he opened with his favorite self-description, "I stand before you as a wartime president" -- Bush pronounced that America's withdrawal from Vietnam led to the Cambodian genocide and the Vietnamese boat exodus. Withdrawal from Iraq, Bush warned, would result in similar catastrophes.

Bush's argument -- which piggybacked on a New York Times Op-Ed piece making the same points by Iraq war supporters Peter Rodman and William Shawcross -- was a gross distortion of history. In fact, almost all historians agree that it was not the U.S. withdrawal that was responsible for the Khmer Rouge's rise to power and subsequent genocidal campaign, but the Vietnam War itself, and in particular President Nixon's massive bombing of Cambodia. The 2,756,941 tons of bombs that first President Johnson and then Nixon dropped on Cambodia -- more than the U.S. dropped in World War II -- drove the devastated rural population into the arms of the Khmer Rouge, which had not been a significant player before America blundered into Vietnam.

Why would Bush choose to bring up Vietnam, a war most Americans see as a quagmire and a mistake, to defend the Iraq war, which most Americans see as a quagmire and a mistake? Even Bush was forced to acknowledge that "[Vietnam] is a complex and painful subject for many Americans" and that "there is a legitimate debate about how we got into the Vietnam War and how we left." By invoking Vietnam, Bush seemed to be going out of his way to invite unflattering reflections on how we got into his own deeply unpopular war.

The White House characterized Bush's speech as a limited argument about the consequences of premature withdrawal. Time's Massimo Calabresi quoted Bush aides as saying that Bush was not trying to "relitigate the Vietnam war," and that his reference was intended only to "deal with the current debate we're in now, weighing the consequences should America walk away from its commitment in Iraq."

But for Bush, Vietnam's real relevance to Iraq isn't the early withdrawal issue -- it's the "stab in the back."

The "stab in the back" holds that America was only defeated in Vietnam because we lost the will to fight. And those who sapped our will, those who betrayed our fighting men, were cowardly protesters and craven politicians. As Bush told "Meet the Press'" Tim Russert in 2004, "The thing about the Vietnam War that troubles me as I look back was it was a political war. We had politicians making military decisions, and it is lessons that any president must learn, and that is to set the goal and the objective and allow the military to come up with the plans to achieve that objective. And those are essential lessons to be learned from the Vietnam War."

As Kevin Baker noted in an in-depth analysis in Harper's, the "stab in the back" thesis is the ur-right-wing credo. It brings together two keystone beliefs: the idea that America is omnipotent and incapable of defeat, and that any war the U.S. engages in must be noble and heroic. Therefore, if America is defeated, traitorous elites -- craven politicians, un-American punks, degenerates, longhairs, pinkos and agitators, and the cowardly elite media -- must be to blame. Nixon and Agnew's demonizing of "nattering nabobs of negativism" and Reagan's claims that war protesters were giving "comfort and aid" to the enemy sprang from this belief.

In fact, the Vietnam War was a terrible mistake, and America pulled out because politicians and the American people alike realized it was unwinnable. But the "stab in the back" myth never died: It stayed alive in the resentment-filled caverns of the American right, for whom it is an article of faith that America's wars are always justified and our military omnipotent. It is not an intellectually respectable idea, but it has currency with Bush's core supporters. Bush usually prefers not to make his ties to the far right so obvious, but his situation is so dire he felt compelled to reach gingerly into this muck of Ramboesque resentment.

The implication of Bush's speech is that there is no real difference between Iraq and Vietnam. It was our moral duty to stay in Vietnam, and we would have eventually prevailed had we done so. Our withdrawal was an unconscionable surrender. And Bush is determined not to let what happened in Vietnam happen in Iraq -- even though there is no military solution to the war. Bush sat out Vietnam in a cushy, and mysteriously absence-filled, stint at the Texas Air National Guard. But now he is implicitly arguing that we should have stayed in Vietnam, and should stay in Iraq, indefinitely.

Needless to say, this is not a winning argument. Its sole virtue is that it invokes the War Myth -- but in a form so debased that it defeats itself. That Bush felt he had to make it reveals the desperate straits he is in.

Equally doomed is the second part of Bush's pro-war P.R. campaign, a paid TV propaganda blitz run by a group named Freedom's Watch, headed by former Bush spokesman Ari Fleischer. The Freedom's Watch ads could be said to represent the reductio ad absurdum of War Mythology -- patriotism as emotional blackmail, jingoism with high production values. The ads -- there are four so far -- use Americans who suffered losses in the 9/11 attacks or in Iraq to bludgeon viewers into going along with Bush's doomed war, implicitly casting critics of that war as defeatists and near-traitors. Thus, an Iraq war veteran who lost a leg is shown saying, "Congress was right to vote to fight terrorism in Iraq and I re-enlisted after September 11 because I don't want my sons to see what I saw. I want them to be free and safe. I know what I lost. I also know that if we pull out now everything I've given and the sacrifices will mean nothing. They attacked us and they will again. They won't stop in Iraq. We are winning on the ground and making real progress. It's no time to quit. It's no time for politics."

Will this blatant appeal to the War Myth work? It has in the past, and the Bush administration seems confident it will again. "The end of August feels much better than the beginning of August," a senior Bush official told the New York Times on Saturday. But this time, the Myth can't save Bush.

Eventually, harsh reality trumps even the totemic power of patriotism. The National Intelligence Estimate released last week confirmed what objective observers already knew: There has been no political progress in Iraq, and none can be foreseen. The situation on the ground, contrary to the rosy reports of U.S. generals, is deteriorating. The Associated Press reported that death tolls in Iraq from sectarian attacks this year are twice what they were a year ago. Also last week, the New York Times ran a devastating report showing that more Iraqis than ever have fled their homes since Bush's "surge" began -- yet another decisive piece of evidence that sectarian hatred in Iraq has long since passed the point at which it can be contained by the U.S.

This is not surprising when you look at the numbers. The war has resulted in an estimated 650,000 Iraqis dead, 1.1 million internally displaced and close to 2.5 million who have fled the country. These figures mean one in six Iraqis has been killed or is a refugee. Translated into American terms, this would work out to 50 million Americans killed or turned refugee -- a figure roughly equal to the population of the northeastern United States, including New York, New Jersey, Maryland and all of New England.

The inescapable truth is that Bush's war of choice has destroyed an entire nation -- and there is no way for the United States or anyone else to control what happens next. The increasingly shaky plight of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki shows just how unstable Iraq's cobbled-together political system is. U.S. dreams of replacing him with a secular strongman like Ayad Allawi are delusional. The war is not winnable, and there is thus only one possible rationale for continuing it, the one Bush raised: preventing an even more apocalyptic blood bath than we have already caused.

If we knew that by staying we could avert such a blood bath, we would owe it to the Iraqi people, whom we have harmed so grievously, to remain. But the fact is that no one can really predict whether our departure will cause such a blood bath. Moreover, it is now obvious that the political and sectarian schisms that could lead to it will not heal themselves. As Gen. Petraeus has admitted, it might take a decade to achieve real stability in Iraq. In other words, Bush is asking the U.S. to keep troops in Iraq, possibly indefinitely, in an attempt to forestall an outcome that might never happen -- precisely what he argues we should have done in Vietnam.

This is not a scenario that Congress or the American people are going to accept. We are now approaching an endgame in Iraq that has its own inexorable logic, which not even Bush's appeals to the War Myth will be able to stop.

In some part of his brain, Bush knows this -- which explains his other motivation for invoking Vietnam and attacking war critics as defeatists. As a partisan Republican, still dreaming of Karl Rove's permanent Republican majority, he wants to ensure that the Democrats take the blame in the coming argument over "who lost Iraq?" By defiantly insisting, contrary to all evidence, that victory is within grasp, he is planting the seeds of a resentful revisionism, a stab in the back II, which he hopes will come to fruition in the future.

The climax of the slow-motion debate over Iraq is approaching. At some point in the near future, it will become inescapably obvious even to congressional Republicans, who hold the key to the decision to stay or go, that the war cannot be won. Bush will continue to proclaim that victory is within sight and accuse his critics of being defeatists.

But the War Myth cannot save him forever, because he's overused it. It will buy him a few weeks or months of breathing space, but even the talismanic power of the War Myth dissipates if people realize it has been used in a cheap, propagandistic way.

One of the problems, ironically for an administration that has sold itself with unparalleled skill, lies in the limitations of advertising. Advertising may be the most potent force in American culture. But war, like religion, is too sacred a subject to be sold in 30-second spots. Bush was able to successfully "roll out his product launch" for the war with a media campaign because that campaign didn't involve explicit advertising. The Freedom's Watch campaign, conversely, is self-defeating precisely because it is bought and paid for. The War Myth, like all myths, works better when the wires that hold it up are not visible.

As for Bush's own speeches, they have about as much credibility as bad advertisements. The president has lived by propaganda. But now that the end is approaching, even propaganda can no longer save him.

Bush's attempt to claim he was stabbed in the back is certain to meet the same fate. That notion will live on only where it always has, in the danker corners of the extreme right wing.

Bush, of course, will never acknowledge any of this. His tunnel vision is terminal, his addiction to the War Myth absolute. In his classic study of the Vietnam War, Stanley Karnow cites a speech made on April 23, 1975, days before the fall of Saigon, by President Gerald Ford. "Today, America can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam," Ford said. "But it cannot be achieved by refighting a war that is finished ... These events, tragic as they are, portend neither the end of the world nor of America's leadership in the world."

Bush will never be capable of uttering such words. He will go down certain that he was right, living the Myth to the end. And because of his addiction to unreality, many more real people will die.

Shares