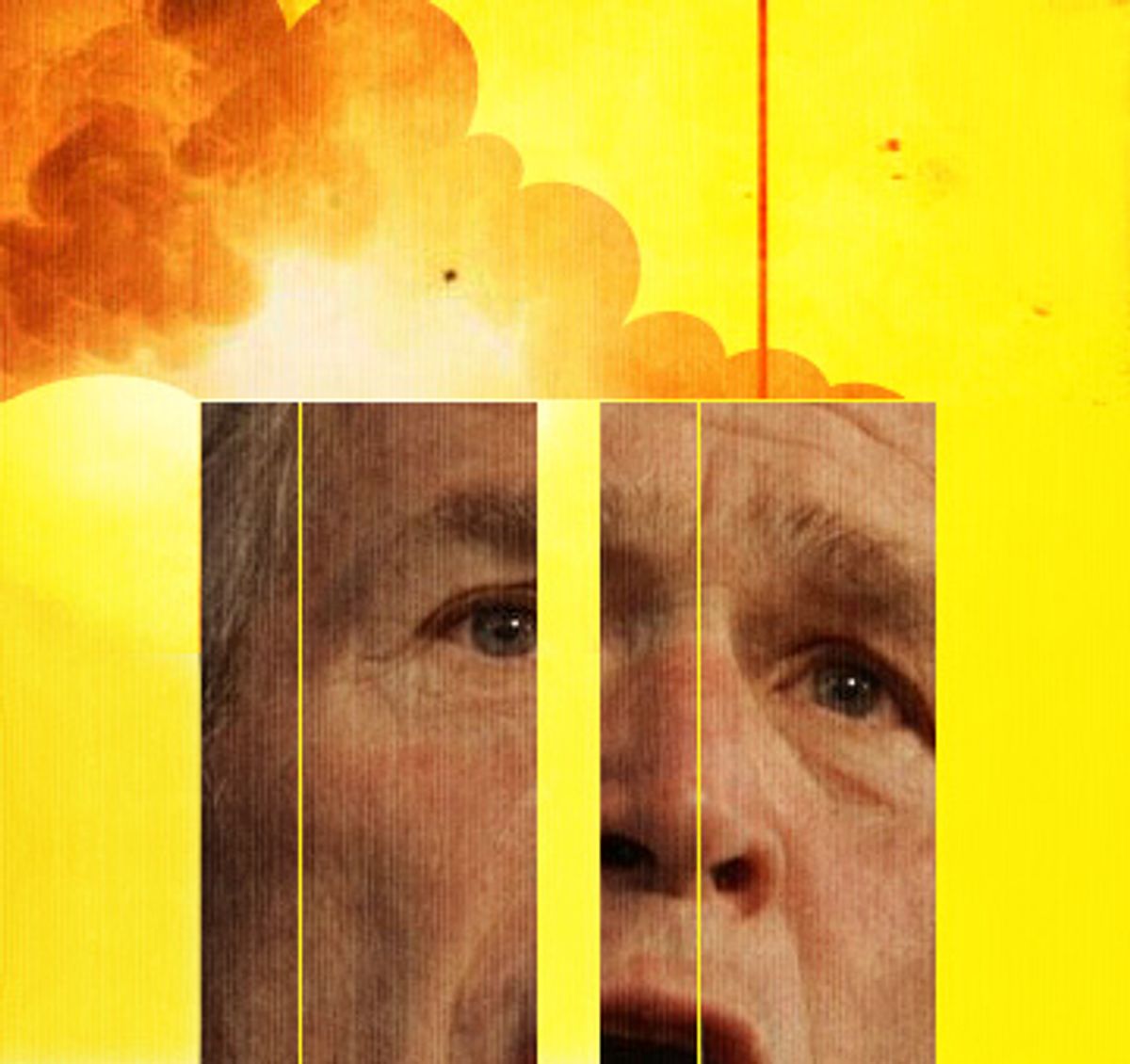

Six years ago, Islamist terrorists attacked the United States, killing almost 3,000 people. President Bush used the attacks to justify his 2003 invasion of Iraq. And he has been using 9/11 ever since to scare Americans into supporting his "war on terror." He has incessantly linked the words "al-Qaida" and "Iraq," a Pavlovian device to make us whimper with fear at the mere idea of withdrawing. In a recent speech about Iraq, he mentioned al-Qaida 95 times. No matter that jihadists in Iraq are not the same group that attacked the U.S., or that their numbers and effectiveness have been greatly exaggerated. It's no surprise that Gen. David Petraeus' "anxiously awaited" evaluation of the war is to be given on the 10th and 11th of September. The not-so-subliminal message: We must do what Bush and Petraeus say or risk another 9/11.

Petraeus' evaluation can only be "anxiously awaited" by people who are still anxiously waiting for Godot. We know what will happen next because we've been watching this movie for eight months. Gen. Petraeus, Bush's mighty-me, will insist that we're making guarded progress. Bush, whose keen grasp of military reality is reflected in his recent boast that "we're kicking ass" in Iraq, will promise that he will reassess the situation in April. The Democrats will flail their puny arms, the zombie Republicans will keep following orders, and the troops will stay.

So let's forget the absurd debate about "progress" and whether a bullet in the front of the head is better than one in the back, and how much we can trust our new friends from Saddam's Fedayeen. On the anniversary of 9/11, we need to ask more basic questions -- not just about why we can't bring ourselves to pull out of Iraq, but why we invaded it in the first place. Those questions lead directly to 9/11, and the ideas and assumptions behind our response to it.

The real reason that Congress cannot bring itself to end the war in Iraq, and incredibly, may be prepared to start another one in Iran, has little to do with benchmarks or body counts. The real reason is that even after the Iraq debacle, the American establishment -- meaning the government and the mainstream media -- has not questioned the emotions and ideology that drove Bush's crusade.

Sept. 11 is a totemic date for the Bush administration. It justifies everything, explains everything, ends all argument. It is the crime that must be eternally punished, the wound that can never heal, the moral high ground that can never be taken. Bush's reaction to 9/11 was to declare a "war on terror," of which the Iraq adventure was said to be the "front line." The American establishment signed off on this war because of 9/11. To oppose Bush's "war on terror" was to risk another terror attack and dishonor our dead. The establishment has now turned against the Iraq front, but it has not questioned the "war on terror" itself, or the assumptions on which it is based.

Bush's, and America's, response to 9/11 was fundamentally flawed for two reasons: It was atavistic and instinctive, and it was based on a distorted, ignorant and bigoted view of the Arab/Muslim world. These two founding errors are qualitatively different: The first involves emotions, the second ideas. But mixed together, they created a lethal cocktail. The grand justification of "spreading democracy in the Middle East" merely provided a palatable cover for vengeance and racism.

Bush's America responded to 9/11 by lashing out. We chose vigilantism over justice, instinct over reason. Bush demanded that America play the role of the angry, righteous avenger, and America followed him. But we were not taking vengeance on the guy who attacked us but on somebody standing on the corner. The war was like the massacre in Haditha on a global scale.

There's a reason why Americans responded to Bush's demand and why Democrats have been afraid to challenge it. It's biological hard-wiring -- after you're hit, your instinct is to hit back. For conservatives, this instinct is not only natural but necessary. Hence the endless right-wing denunciations of war critics as wimps, girly-men and appeasers.

Gender images play a significant role. The right wing embraces a cartoonlike image of masculinity because it believes that only an alpha male can protect America from its enemies. (In a recent essay in the New York Times, Susan Faludi argued that such retrograde gender images have been used to construct the American self-image from the earliest days of our presence on this continent.) This is part of the reason that Bush has put forward Gen. Petraeus as the cheerleader for the war. Petraeus is the ultimate alpha male, right down to his rigorous workout routine. In the Hobbesian world of the conservative imagination, the big club rules, and he who puts down the club will be brained by another unfettered troglodyte, be it a communist or an "Islamofascist." Nature is red in tooth and claw, and those who dream of transcending nature or transforming it will be destroyed by it.

The fetishization of the "natural," of which instinct is only a part, is key to conservative thought. In the early '60s, conservatives like Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan defended the right of individuals and states to practice segregation because that decision was instinctual and organic. They saw the federal government's attempt to outlaw segregation as artificial and coercive.

Of course, instincts play a vital role in human life: They underlie virtually all of our thoughts and actions. To ignore them is to fall into a deracinated world of sterile rationality. Lashing out is sometimes an effective way to defend yourself. But instinct is atavistic and often self-defeating. Higher-level mental functions came into existence to control and refine it. Both individuals and states have learned that they should not base their reactions merely on animal instincts. That's why law arose: to prevent every injury from turning into a destructive and endless feud. Retribution is a legitimate motive for punishment but only to a point. It is limited by the higher concept of justice. Justice not only prescribes the extent of the retribution that is morally acceptable, but insists that the context of the crime, including the criminal's history and state of mind, must be considered before meting out punishment.

Democrats have effectively challenged the reign of nature and instinct in the domestic realm. But they cower when it comes to war. They are afraid to criticize the irrational, instinctive nature of Bush's "war on terror" because they believe their political Achilles' heel is the perception that they are "weak on national security." They are afraid they'll be seen as wimps. Beaten down by Republican propaganda that asserts that America's only choice is between the GOP's macho John Wayne and the Democrats' dithering Hamlet, they pathetically don their cowboy hats and tank helmets, a tactic that actually reinforces the very image of weakness it is intended to dispel. Unchallenged by the Democrats, the right wing's master narrative about American power and the need to carry a big stick has carried the day.

Of course America was enraged and fearful after the attacks. But reacting to the attacks as we did, like an angry drunk in a bar, was not in our national interests. It was vital that we think clearly about our response, who attacked us, why they did, and what our most effective response would be. But here the American establishment ran up against its ideological blind spot -- its received ideas about the Arab/Muslim world. Combined with the hysterical emotionalism, those ideas, which amount to a kind of de facto bigotry, allowed Bush to push through one of the most bizarrely gratuitous wars in history.

We attacked Iraq because of 9/11. That is the scandalous and surreal claim that reveals our fatal emotional-ideological flaw. Anyone who knew anything about the Middle East knew that Saddam Hussein, a secular tyrant, had nothing to with 9/11 or al-Qaida. War defenders like to claim they were "misled by bad intelligence" into thinking Saddam had WMD. But there was no new evidence that Saddam posed a threat. He was the same old Saddam. He only became frightening in light of our prejudice against Arabs and Muslims. Moreover, despite the appalling effectiveness of the 9/11 attacks, it was clear that al-Qaida posed no existential threat to either America or to the Middle East. As the invaluable analyst Juan Cole has pointed out, apocalyptic Salafi jihadists like al-Qaida were an isolated and weak force within the Arab-Muslim world -- or at least they were until Bush invaded Iraq.

The angry bigotry that drove the war rings out loud and clear in the right-wing battle cry: "They attacked us, so we had to attack them." The recent TV ads run by war supporters repeat this theme: "They attacked us," a narrator says as an image of the burning World Trade Center appears. "They won't stop in Iraq." The key word here, of course, is "they." Just who is "they"? For Bush's die-hard supporters, "they" simply means "Arabs and Muslims." Cretinous rabble-rousers like Ann Coulter and Michael Savage play to this crowd, demanding that we nuke the evil ragheads. For the establishment, "they" is not quite so explicitly racist. "They" refers not to all Arabs and Muslims, but only to the "bad" ones. The "bad" guys include al-Qaida, Iran, Syria, Hezbollah and the militant Palestinians. And, of course, it used to include Iraq (and may again). Anyone who makes this list is eligible for attack by the U.S.

What makes these wildly disparate entities so evil and so threatening that we're prepared to attack them without cause? Simply that they reject the U.S.-Israeli writ in the Middle East -- and that they're Arabs or Muslims. They are clearly not on our side, but they pose no significant military or economic threat to the U.S. In realpolitik terms, they are no more beyond the pale than many other dubious countries we do business with, from Venezuela to Nigeria to Russia to Saudi Arabia. No one would dream of suggesting that if Cuba attacked the U.S., we should respond by invading Venezuela. But we play by different rules in the Middle East.

America's anti-Arab, anti-Muslim prejudice has several causes. One of them derives from America's powerful identification with the one state that has always been at war with the Arab-Muslim world: Israel. For the establishment, it is axiomatic that America's and Israel's interests are identical, and that enemies of Israel must be enemies of the U.S. America has always identified more with Israel, the plucky underdog and home to Holocaust survivors, than with the Arabs and Muslims who threaten it. Since this view is held by right and left, Democrat and Republican alike, and criticizing it leads to accusations of anti-Semitism, it is difficult to challenge it. This is the reason why there has been almost no discussion in Congress over Bush's saber-rattling with Iran: Iran is Israel's most dangerous enemy, and that fact trumps all other considerations.

America's Israel-centric stance has helped determine the way we see the Arab-Muslim world, but it isn't the only factor. The rise of radical Islam, with its cult of martyrdom and terrifying terrorist attacks, exacerbated America's existing prejudices, flattening out the Arab-Muslim world into a monolithic entity. Our almost complete ignorance of Arabs and Islam, their history and the actual grievances that they have against the West, contributed to this flattening. Oil plays a role. But perhaps the most potent explanation of all is simply the fear of the Other: Islam is not in our cultural tradition, it stands apart, it's mysterious and ominous, and it is all too easy to project our fears on it.

One sure sign of cultural bias is the presence of high-flown concepts. Mission civilatrice, the White Man's burden, is inevitably accompanied by lofty rhetoric. Iraq was all about Grand Theory.

One of the neocons' main goals in invading Iraq was to "remake the Middle East" -- a weirdly grandiose, imperialist concept of the sort that doesn't apply anywhere except with Muslims. Only in the Middle East do lofty historical generalizations about why a world culture went wrong -- like those of the right-wing Arabist and White House favorite Bernard Lewis -- provide the intellectual underpinnings for unprovoked wars. Yes, the Arab-Muslim world has some serious problems, and yes, only a politically correct pedant would forbid all cultural generalizations. But when you go to war on the basis of those generalizations, you cross the line into colonialist prejudice.

The most lofty, abstract generalization of all is the insistence that this is a war of good vs. evil. "They" attacked us not because they had grievances or for any reasons that exist in the sublunary realm: They attacked simply because they were evil. Saddam would do the same because he, too, like Syria, Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas, was evil. The "war on terror" is a crusade, a Holy War, whose essentially theological nature was summed up by the title of Richard Perle and David Frum's book, "An End to Evil." And once you're dealing with "evil," niggling distinctions -- between Sunni and Shiite, or secular and religious, or whether the country you want to invade had anything to do with attacking you -- can be dispensed with.

The failure of the American establishment to question such ideas, and its willingness to sign off on a war based on them, amounts to a kind of de facto bigotry: Kill one Arab, send a message to the rest of 'em. Attacking Iraq because of 9/11 made about as much sense as attacking Mozambique after the Watts riots. If we had done something that insane, we would be accused of being racists. We wouldn't be able to shake the accusation, no matter how much gobbledygook apologists came up with about bursting a "terrorism bubble" or the "pathologies of black culture." But when America did something equally insane and attacked Iraq in response to 9/11, no one accused it of racism. Instead, we got a lot of sophistry about "Islamofascism" and other Aquinas-like attempts to make 99 virgins dance on the head of a Baathist.

Sept. 11 was a hinge in history, a fork in the road. It presented us with a choice. We could find out who attacked us, surgically defeat them, address the underlying problems in the Middle East, and make use of the outpouring of global sympathy to pull the rest of the world closer to us. Or we could lash out blindly and self-righteously, insist that the only problems in the Middle East were created by "extremists," demonize an entire culture and make millions of new enemies.

Like a vibration that causes a bridge to collapse, the 9/11 attacks exposed grave weaknesses in our nation's defenses, our national institutions and ultimately our national character. Many more Americans have now died in a needless war in Iraq than were killed in the terror attacks, and tens of thousands more grievously wounded. Billions of dollars have been wasted. America's moral authority, more precious than gold, has been tarnished by torture and lies and the erosion of our liberties. The world despises us to an unprecedented degree. An entire country has been wrecked. The Middle East is ready to explode. And the threat of terrorism, which the war was intended to remove, is much greater than it was.

All of this flowed from our response to 9/11. And so, six years later, we need to do more than mourn the dead. We need to acknowledge the blindness and bigotry that drove our response. Until we do, not only will the stalemate over Iraq persist, but our entire Middle Eastern policy will continue down the road to ruin.

Shares