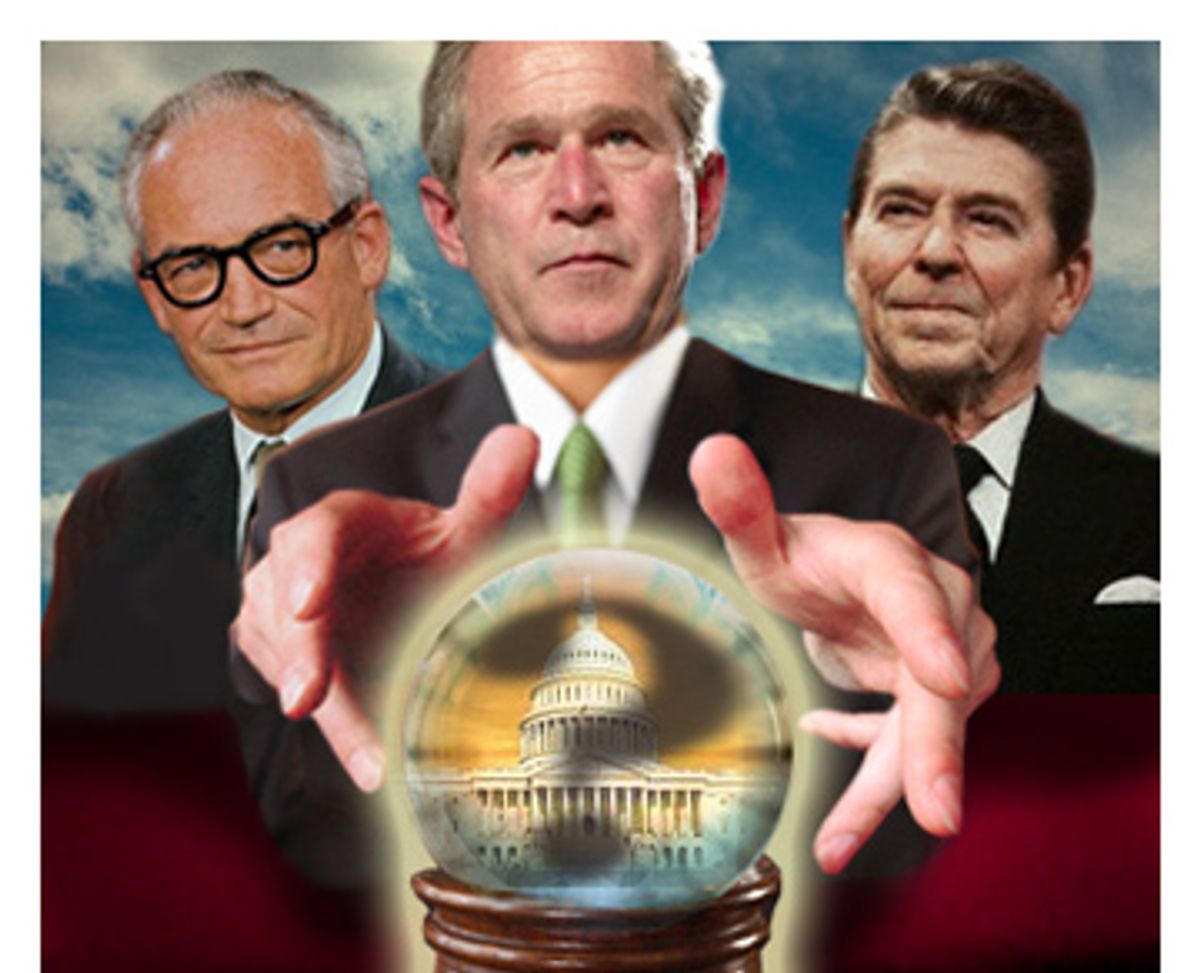

Last week, I argued that George W. Bush's presidency represents a radical departure from the principles of American conservatism. By covertly manipulating the country into a disastrous war of choice, vastly expanding the power of the executive branch, and approving of torture and warrantless wiretapping, among other things, Bush has trashed the tradition of Jefferson and Burke.

What I was trying to do was identify certain core conservative principles -- primarily a belief in personal agency, a respect for tradition, and a wish to preserve organic community -- that even liberals would not find objectionable and to point out that Bush has betrayed these conservative principles to an unprecedented degree. This raises the issue of why anyone who considers him- or herself a conservative would support Bush or his party.

In response, a number of readers argued that since no conservative president has ever lived up to those conservative principles, they're basically irrelevant. These readers maintained that in the real world, as opposed to my vaporous and too-charitable musings, conservatism is about nothing but power (or tribalism, or selfishness, or resentment, or xenophobia). The Bush presidency thus does not represent a perversion of American conservatism but its logical culmination.

I think these readers are right about American conservatism in practice. Bush is indeed the natural heir of the ideology that runs through Goldwater, Nixon and Reagan. But I think they're wrong that the conservative movement is foreordained to remain in its current debased form.

The real question concerns the nature of the conservative principles -- or, more precisely, the relationship of those principles to conservative practice. Conservative ideals are laudable: Who is against freedom, tradition or the preservation of community? The problem is that while they're beautiful in the abstract, it is difficult to base a coherent governmental policy on ideals alone. Once these principles enter the real world of politics, governance and society, a world that requires compromise and the curtailment of individual freedom for the common good, they are useless as guideposts. If they are taken as moral absolutes, they cancel each other out: The apotheosis of the individual leads to the destruction of community and tradition.

American conservatism is at once absolutist and utopian, and reactive and aggrieved. Which state came first is a chicken-and-egg question, but they reinforce each other. Psychologically, conservatives want contradictory things -- both pure freedom and an unchanging Golden Age. Pragmatically, they want things that are mutually exclusive -- no social contract and an organic, connected community, untrammeled individual rights and a rigid moral code. The inevitable disappointment results in resentment. The reason that the American right always behaves as if it is an angry outsider, even when it controls all three branches of government, is that it is at war not with "liberalism" but with social reality.

Therefore, it is not sufficient to argue, as I implicitly did in my earlier piece, that all that conservatives need to do is return to their principles. Rather, they need to acknowledge that purity is impossible. They need to come to terms with the fact that unlimited freedom results in the tragedy of the commons, in which the unchecked actions of individuals destroy the common good. Real politics consists of negotiations between two goods, the good of freedom and the good of society.

A conservatism that accepted the need for compromise would still be conservative. There will always be substantive issues on which conservatives and liberals will have good-faith differences. It would simply be a more mature conservatism.

The history of American conservatism does not inspire much confidence, however. In spite of its moderate roots, it has succeeded mainly via absolutist, reactionary politics. This approach has enormous emotional appeal for Americans for whom the modern world is a source of confusion, anger and fear, or who simply disdain the social contract . And the Republican Party is now entirely in thrall to it. The current crop of GOP candidates hold uniformly hard-right positions, with the exception of the libertarian, no-chance Ron Paul. The leading GOP contender, Rudy Giuliani, is even more of a maniacal hawk than Bush on the Middle East and national security. These are hardly signs that the right is moving to the center.

But sooner or later, conservatives will have to change course or see their movement wither away.

The issues that have been winners for conservatives are fading. White resentment of federal civil rights laws is the ur-conservative issue, the engine that drove the right's rise. Barry Goldwater, by reluctantly voting against the Civil Rights Act, permanently realigned the South and paved the way for Nixon's "Southern strategy." More recently, right-wing strategists successfully mobilized resentment over "values" issues like the "three Gs" -- gays, God and guns. These issues still mobilize some conservative voters, but they aren't nearly as effective as they used to be. Studies show that the electorate, especially younger voters, are moving left on these issues.

Support among voters for conservatism's powerful no-more-taxes wing is dwindling as well. As Bush found out recently, Americans will do anything to save the nation's two largest entitlement programs, Social Security and Medicare, including paying higher taxes.

The fall of communism was another heavy blow to the conservative movement. It was fear of communism, added to white backlash, that handed conservatives control of the country in the Reagan years. Although Bush won reelection in 2004 by convincing enough frightened Americans that a nonexistent entity called "Islamofascism" was the second coming of the Evil Empire, that fear-mongering comparison will not work anymore. The Iraq debacle, and Bush's misguided "war on terror," have made it only too clear that moralistic militarism and disdain for diplomacy only makes the problem worse.

Bush's disastrous presidency has revealed many other shortcomings in conservatism. The Katrina debacle reminded Americans that government's first duty is to be competent, not ideological. The endless crony-capitalism scandals of the Bush years, from Enron to Halliburton to Blackwater, showed that Bush's version of the "free market" is a rigged game. And his hectoring, mean-spirited presidential style has divided America and made our civic life remarkably ugly.

So if conservatism is to survive, it will have to make hard choices. To win leftward-moving centrists, it will have to jettison its extreme positions on both social issues and on economic policy. In effect, this means a return to the moderately pro-business conservatism of Eisenhower.

Of course, the Democratic Party is moving in a similar centrist direction. The old labels "liberal" and "conservative" mean less and less in the world of postindustrial capitalism. To be sure, there are legitimate issues on which conservatives and liberals differ and will continue to differ -- like affirmative action, or immigration, or the degree to which government ought to try to ensure quality of outcome as well as equality of opportunity. The arguments over such matters are necessary, and they will continue. But the most critical issues that America faces can no longer be described using the old labels. For example, what is the "conservative" or "liberal" position on globalization? Or on how to deal with international terrorism? Or whether to use American power for humanitarian ends? The old labels are meaningless here.

In the end, conservatism will have to decide if it wants to be a real party of governance, moving beyond empty labels to engage with real issues, or if it wants to remain a party of reaction, in permanent rebellion against modernity, proffering emotionally satisfying but incoherent policies. Conservatism claims to be a politics of authenticity, but it is actually a politics of impulse and instinct. It is based on unmediated emotions, erupting from the individual ego -- Get big government off my back! Keep those civil rights laws out of my white backyard! Lower my taxes! This is ultimately an infantile or an adolescent politics, a failure to come to terms with a world that does not do exactly what the omnipotent self demands. Does conservatism want to grow up, or stay an angry teenager forever?

If conservatism chooses to follow its current course, it will grow ever narrower, angrier, more divisive and more partisan. But there is another possibility: It could evolve into a movement not just of reaction and self-canceling absolutism -- but of hope and inclusion.

This new conservatism would try to conserve the best of traditional America, but understand that change is innate in that tradition, and that, paradoxically, tolerance and flexibility are needed to preserve it. It would try to guide its fearful constituents gently into the modern world, not pander to their fears. It would be patriotic but possess the self-confidence of mature patriotism. This would allow it to throw out the Manichaean moralizing and militarist triumphalism that has characterized conservatism from Reagan's simplistic anti-communism through Bush's "war on terror," and strengthen America by rooting it more firmly in the international community, not less. It would try to create a real, engaged morality, instead of a cheap simulacrum based more on resenting differences than on trying to realize the ideals of altruism and brotherhood. It would celebrate a religious vision like that of Martin Luther King Jr., one that could be an inspiration to all Americans, whether believers, agnostics or atheists.

The new conservatism would not be liberal. It would still tilt toward small government and lower taxes, would reject policies aimed at equal outcomes, would oppose affirmative action and unrestricted immigration. That's why it would be conservative (and, anticipating outrage from liberal Salon readers, why I wouldn't support it). But it would abandon its facile government bashing and appeals to raw emotion. Above all, it would aim at working to build an America that, despite political differences, would pull together, would feellike a united country. It would take seriously that old saw about one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

It's hard to imagine the party of Karl Rove and Rush Limbaugh moving to the center. But if Americans turn away from the politics of resentment and fear, the GOP may be forced to follow them.

Shares