Trying to figure out what Barack Obama intends to do in the Middle East is like trying to read the leaves in a cup of tea stirred by Jackson Pollock. For every signal Obama has given that he intends to break decisively with Bush's failed approach to the Middle East, he has given another that indicates he plans to simply give the same policies a fresh coat of paint.

Obama took what many regarded as a backwards step even before assuming office by appointing Hillary Clinton, who supported the Iraq war and as senator toed the establishment line on Israel, as secretary of state. But then he gave his first presidential interview to the Arabic-language station al-Arabiya and announced that his administration would approach the Arab-Muslim world with a spirit of respect and willingness to listen. He said, "If countries like Iran are willing to unclench their fist, they will find an extended hand from us." But then he named as his Iran advisor the right-leaning Dennis Ross, who signed a threatening Iran paper drafted by two hard-line neoconservatives, claimed, in a statement to Congress accompanying his renewal of sanctions against Iran, that the country posed "an extraordinary threat" to the U.S. and gave every indication that he would continue Bush's failed carrots-and-sticks approach. Obama has ordered a top-to-bottom strategic review of U.S. policy toward Afghanistan and Pakistan, but sent 17,000 more troops there and has continued to assassinate militants in Pakistan with missiles fired from Predator drones. He announced that he was winding down the Iraq war, but is doing so at a hyper-cautious pace.

Not surprisingly, Obama's most contradictory messages concern the most important, and politically radioactive, issue of all: the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. His appointment of the respected negotiator George Mitchell as special envoy for the Middle East was taken as strong evidence that he was prepared to challenge Washington's blank-check support for Israel. In a major break with the Bush administration's refusal to deal with Hamas, Mitchell told Jewish leaders that a Palestinian unity government made up of the U.S.-backed Palestinian Authority and Hamas would be "a step forward" for peace. Similarly, after Britain announced that it would break with U.S. and European policy by beginning low-level contacts with Hezbollah, an anonymous State Department official told reporters that the U.S. might enjoy some benefits from the diplomatic rapprochement. "We are looking for a comprehensive approach" in the Middle East, the official said. For her part, Secretary of State Clinton, on her first trip to the Middle East, criticized Israeli house demolitions in East Jerusalem, albeit in feeble, Condoleezza Rice-like terms as "unhelpful," and hinted that the Obama administration was prepared to challenge the ongoing expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. She also pledged $900 million in U.S. aid to rebuild Gaza after Israel's devastating 22-day onslaught earlier this year.

All of these developments represent a significant change from Bush administration policies on Israel-Palestine. But the Obama administration's right hand proceeded to undo what its left one had done.

Having sent signals that it might be prepared to break with Bush's policy of excluding Hamas and Hezbollah, the Obama administration proceeded to exclude them. Secretary of State Clinton has continued the Bush administration policy of dealing only with Fatah, the dominant faction in the Palestinian Authority (PA) headed by Mahmoud Abbas. She ordered that U.S. funds for Gaza go only to the PA, not Hamas. And in direct contradiction of the cautious support for a British-Hezbollah thaw expressed by an anonymous Obama official, another anonymous official sharply criticized it.

The most glaring sign that Obama might continue the status quo on Israel was his failure to defend Charles Freeman. Obama's director of national intelligence, Admiral Dennis Blair, had asked Freeman to head the National Intelligence Council, but the highly respected diplomat withdrew after he was heavily attacked by supporters of Israel, including neoconservative ideologues and politicians from both sides of the aisle, such as the Democratic New York senator Charles Schumer. "His statements against Israel were way over the top and severely out of step with the administration," Schumer said. Obama's refusal to stand up for Freeman indicates that he is unwilling to challenge Washington's quasi-official, bipartisan policy of unswerving support for Israel, and raises serious questions about whether he will be prepared to confront the incoming right-wing Israeli government led by Benjamin Netanyahu. But if he fails to do so, all his diplomatic overtures in the region will only be so much hot air.

Obama has broken with Bush's Middle East policy in one key area: He is talking to more players in the region. The most notable difference concerns Syria. Bush demonized Syria as a junior-varsity member of the Axis of Evil and refused to deal with it, but Obama is talking to Damascus and encouraging it to resume peace negotiations with Israel. His strategic purpose is to drive a wedge between it and its fellow hardline state Iran, thus weakening the militant rejectionist groups Hamas and Hezbollah and strengthening Fatah. This is a good idea as far as it goes, and it represents a qualified change from the Bush strategy of trying to line up the "moderate" states of Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan against the "extremist" ones, Iran and Syria and their militant clients.

The problem, however, is that it is only a qualified change, because Obama is still refusing to deal with Iran and the militant groups, hoping they can be marginalized. But they cannot be marginalized unless the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is resolved. Obama can fiddle around the edges all he wants, make all the right noises, but unless he is willing to deal with the real problem, his Middle East policy will go nowhere.

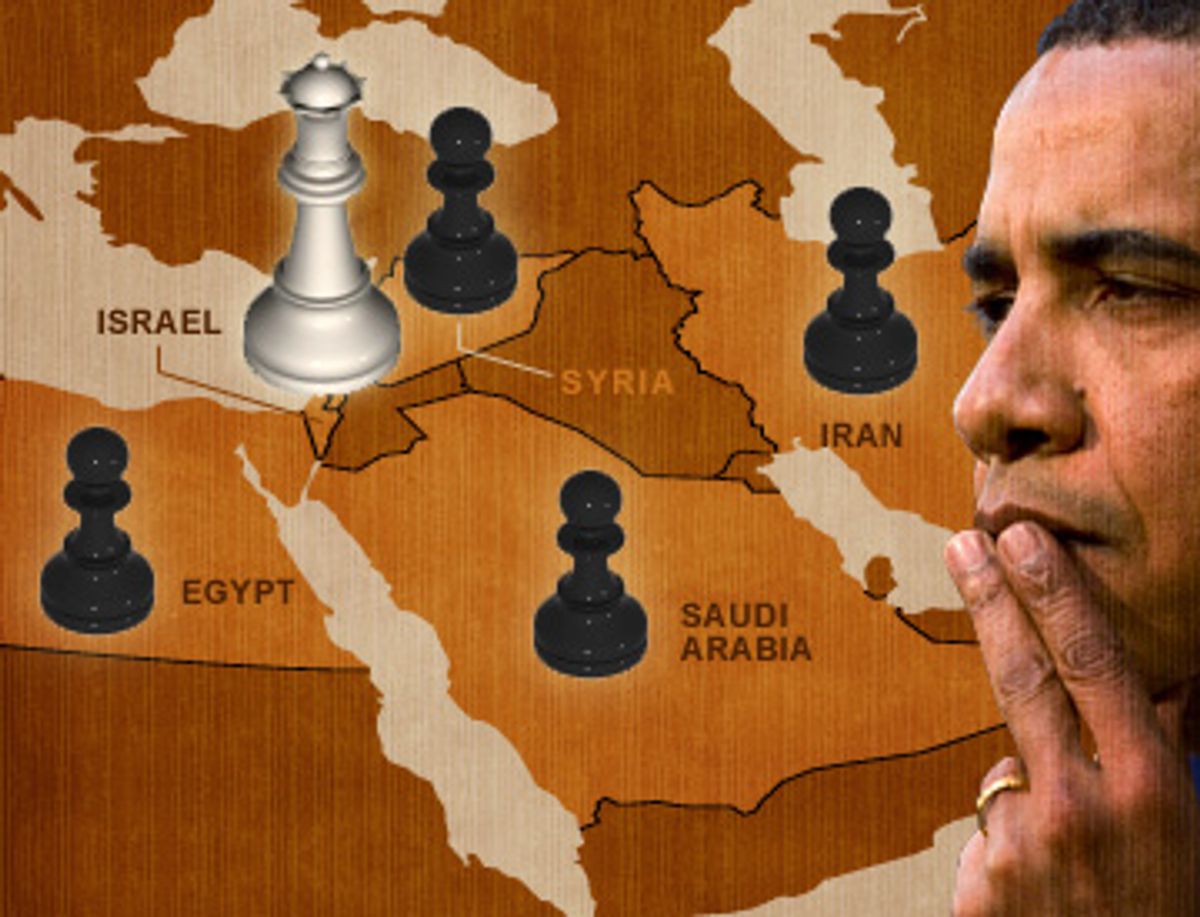

His cautious and contradictory moves so far give the impression that Obama hopes that more diplomacy will somehow cause the chess pieces on the Middle East board to move in such a way that he will be able to broker an Israeli-Palestinian peace without going head-to-head with Israel. But that hope is unrealistic.

Capitalizing on their fear of Iran, which his Iraq war greatly strengthened, Bush prodded the "moderate" Arab states to close ranks against the "extremists." So far, Obama is following a similar path -- with the only difference being that he has opened communication with Syria. But the "moderates," their legitimacy badly damaged by Israel's Gaza onslaught, never fully embraced that strategy, and they have now rejected it. They still distrust Iran, but they have come to realize that the only way to weaken it and its militant proxies is by addressing the root cause of extremism: the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. That's why the Arab states have been engaged in furious diplomacy in the run-up to the upcoming Arab League summit in Qatar -- including reaching out to Syria. The recent four-way meeting in Riyadh between King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, Syrian president Bashir Assad, Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and Kuwaiti emir Sheikh Sabah Al Ahmad Al Sabah ended with a pledge to speak with one voice on Israel-Palestine.

The fact that all the Arab states have adopted a uniform position on the Israeli-Palestinian crisis, demanding that it be resolved along the lines of the 2002 Arab Peace Plan, spells a death knell for Bush's attempt to use the "moderate" regimes' fear of their own Islamist radicals to sideline them on Israel-Palestine. And it puts the onus squarely on the U.S., and its client Israel, to take immediate and concrete steps towards a two-state solution.

Seen in this light, Israel's Gaza war was a major strategic blunder. Not only did it achieve nothing militarily -- the crude rockets it was ostensibly intended to stop continue to rain down, Hamas is more popular than ever, and Abbas is weaker -- but it united the Arab states against it. The Saudis and Egyptians fear Iran and were enraged after Syria's Assad derided them as "half-men" for failing to oppose Israel, but after Gaza they had no choice but to present a united front on Israel-Palestine. As Agence France-Presse reported on the recent Riyadh meeting, "[T]he Saudis see themselves as 'delivering' the Arabs to comprehensive peace talks, hoping to provoke the Obama administration to 'deliver Israel' -- regardless of who is leading Israel's government. Riyadh wants to maneuver Israel into 'a put up or shut up' situation, said one foreign analyst."

U.S. hopes that Syria can somehow be persuaded to break with Iran are misguided. As Syrian analyst Marwan Kabalan told the National, "Syria believes it can have good ties with Iran and America, that it does not have to choose between one or the other." The only way for America to undercut Iran, Kabalan said, was to broker an Israeli-Palestinian peace. "The answer is the peace process, and not just a deal between Syria and Israel over the Golan," he said. "If you want to undercut Iran, you don't need to ask Syria to move away from Iran, you just need a fair peace. Peace will automatically mean that Hamas and Hizbollah are playing a more political role."

As Kabalan's comments suggest, neither Syria nor Iran is going to drop its support for the militant groups until there is a viable Palestinian state. Nor are Hamas and Hezbollah going to give up armed resistance until the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land ends. This leaves Obama no choice: If he wants to stabilize the Middle East, prop up the "moderate" regimes and disarm the militants, he has to pressure Israel to accept a two-state solution. America's present policy, demanding that the rejectionist and radical Arab factions agree in advance to renounce violence and recognize Israel while not simultaneously demanding that Israel end the occupation and return to its 1967 borders, has not worked, will not work and is simply a recipe for a continued conflict. And time is not on Israel's side.

But demanding that Israel take the steps necessary to make peace means a harsh face-off with the Netanyahu government. If the Gaza war moved the Arab states to the left, it moved Israel to the right. On Monday, it was announced that Avigdor Lieberman, a bigoted ultra-nationalist who ran an explicitly anti-Arab campaign, would be Netanyahu's Foreign Minister -- the equivalent of Obama naming George Lincoln Rockwell or David Duke to be his secretary of state. The stage is set for a major collision.

Obama's cautious moves so far, and the lengths he went to before the election to assure right-wing American Jewish groups like AIPAC that he was staunchly pro-Israel, suggest that he wants to avoid that confrontation at all costs. A showdown with Israel will split the Democrats, threaten campaign donations and distract attention and resources from his domestic agenda. But unless he is content with the status quo, he has no choice. If he wants to stabilize the Middle East, deal justly with the Palestinians, reduce the threat of jihadist terrorism and ensure a secure future for Israel, he will have to seize the third rail of American politics.

The fact is that the U.S. desperately needs a game changer in the Middle East, and brokering an Israeli-Palestinian peace along the lines of the 2002 Saudi peace initiative or the 2003 Geneva Accord is the only game changer we have left.

Under Bush, the neoconservatives tried their own game changer, reversing the old mantra that the road to Tehran and Baghdad runs through Jerusalem. But it turned out conquering Baghdad did not open the way to an undivided, Israel-run Jerusalem. Israel's enemies, contrary to neoconservative dreams, did not cry uncle. In fact, the rejectionists among them are more powerful than ever.

The new Middle Eastern diplomatic detente leaves Obama only one way forward. If he wants to succeed, he will have to make it clear to the far-right Israeli government that it must stop settlements, return to its 1967 borders and accept a viable, contiguous Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.

If Obama dares to do this, he will find himself in a political storm like none he has ever seen. But there is reason to believe that Americans are starting to think about Israel and Palestine in a new way. Israel's brutal attack on Gaza badly damaged its international standing: Only its most hard-line supporters defend that atrocity. Roger Cohen's confession in the New York Times that "I have never previously been so shamed by Israel" expresses a widespread sentiment. Even the Israel lobby's victory on Freeman may have been Pyrrhic. As IPS's Jim Lobe, whose reporting on the neoconservatives and the Israel lobby stands above all others, pointed out in a piece he co-wrote with Daniel Luban, the Freeman affair forced the mainstream media to at last acknowledge the elephant in the room: that there is an Israel lobby, and that it wields enormous power. (When Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer published "The Israel Lobby" in 2007, they were widely accused of being anti-Semitic, scurrilous charges that have now mostly disappeared.) Unswerving support for Israel is still official America's default position, but it is becoming more and more hollow as politicians and American Jews alike begin to question whether such "support" is in America's, or even Israel's, interest.

Obama also has some political cover. The Iraq Study Group report made it clear that significant parts of the American foreign-policy establishment reject Bush's good-and-evil approach. Now, another blue-chip group of senior foreign policy officials, including Brent Scowcroft and Zbigniew Brzezinski, have urged the U.S. to open a dialogue with Hamas.

Paradoxically, the huge gulf between the Obama administration and the Netanyahu government could actually make it easier for Obama to broker a peace deal. As veteran analyst Henry Siegman, president of the U.S./Middle East Project, recently argued in Haaretz, center-left Israeli governments have never been willing to take the steps necessary to make peace: They have "used the peace process they champion as a cover for the continued expansion of settlements and the closing off of East Jerusalem to any future Palestinian entity." But American presidents have been unwilling to challenge any Israeli government that pays lip service to the two-state solution, which means that such governments can stall forever. By contrast, Siegman notes, "a Netanyahu-led government with coalition partners like Avigdor Lieberman and other extreme right-wing parties that do not enjoy much popular support in the U.S. (or anywhere else for that matter) would allow President Barack Obama and his administration to advance [a peace] initiative."

Finally, there is Obama himself. Elected to bring change, in the wake of a disastrous war whose intellectual architects were ardently pro-Israel, he has more of a mandate to change the imbalanced U.S. policy toward Israel and the Palestinians than any recent president.

So Obama has the power, and probably the wisdom, to change America's misguided course in the Middle East. Whether he has the will, or the courage, is another question.

Shares