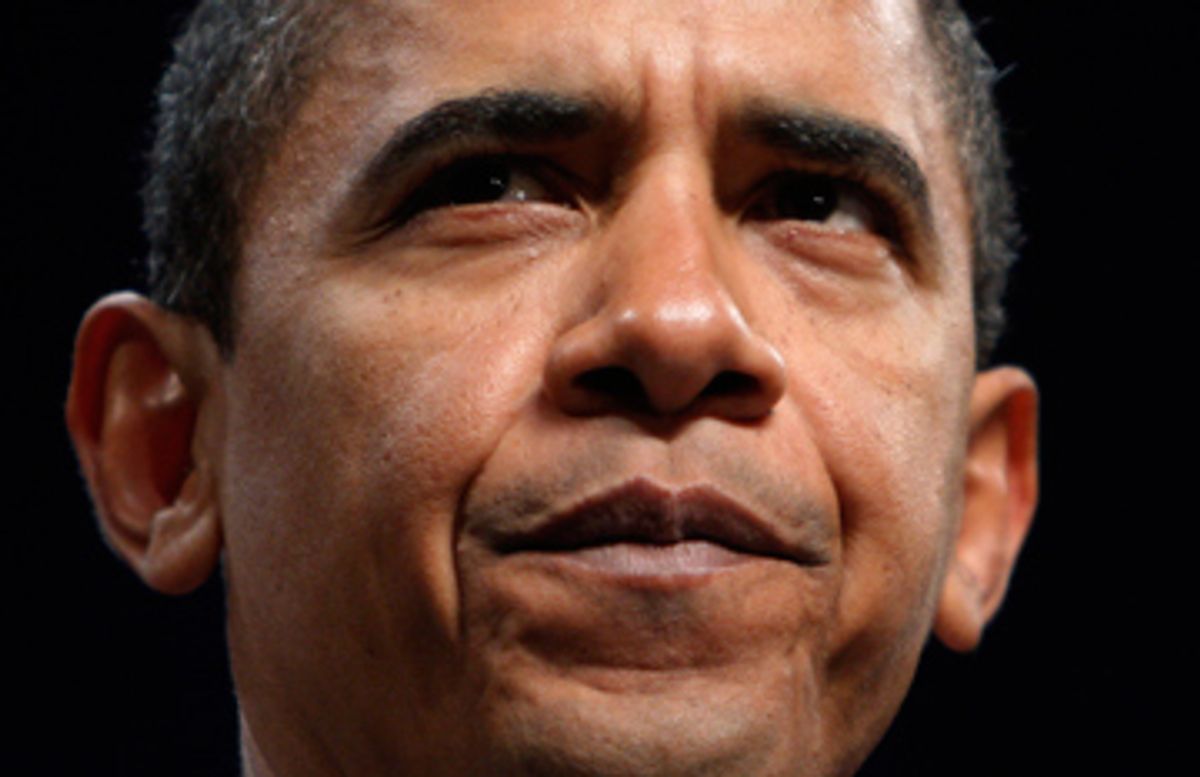

The hard sell that Barack Obama put on last week went beyond the normal political smooth-talking that presidents (or presidents-elect) sometimes use to promote their legislative agenda and crossed over into something a bit more urgent.

"For the sake of our economy and our people, this is the moment to act and to act without delay," Obama said Friday, pushing Congress -- for the second day in a row -- to get moving on a massive $775 billion economic stimulus plan as soon as possible. (On Thursday, he'd devoted an entire speech to the plan, the first time he'd given what his staff had billed as a "major policy address" since he won the election.) "The American people are struggling. And behind the statistics that we see flashing on the screens are real lives, real suffering, real fears. And it is my job to make sure that Congress stays focused in the weeks to come and gets this done." His Saturday radio/YouTube address had more of the same; the transition team simultaneously released a 14-page report claiming Obama's plan would create 3 to 4 million jobs by the end of next year.

But the main target of his blitz isn't necessarily voters, who polls show are on board with just about anything that will help save jobs. And it isn't the Republican opposition in Congress; they may not go along with the plan in the end, but Democrats have big enough margins in both the House and the Senate that they shouldn't need too many GOP votes to pass Obama's plan. As it turns out, that's the problem: Democrats, who with their expanded majorities were supposed to make it easy for Obama's agenda to cruise through Congress, started objecting to the stimulus plan as soon as details leaked to the press. The objections were pretty basic: Obama wanted to spend too much on tax cuts, and not enough on infrastructure. The criticims were mildly phrased, but there was no question that Obama and his aides would have some work to do to push the stimulus plan into law. (They already had to scrap their hope of having the bill ready for Obama to sign on Jan. 20, which turned out to be impossible, and are now aiming for mid-February, before the first recess of the year.)

"There are some differences of opinion as to how to approach this thing," said Dick Durbin, D-Ill., the second-ranking Democrat in the Senate, after the party held a closed meeting Thursday with Larry Summers, a senior Obama economic advisor, and David Axelrod, his political guru. "There was no violent reaction against it, but there are people saying, 'Would you consider this as part of it?'" Nebraska Democrat Ben Nelson, who isn't exactly a raving liberal, said the tax cuts didn't win him over any more than they did most of his colleagues. "Tax cuts are going to be persuasive to some quarters, no doubt about it, but others are going to have the question of whether it's just trickle down or trickle up," he told Salon after leaving the meeting. Democratic leader Harry Reid, of Nevada, went even further, flatly stating Obama would have to compromise. "Barack Obama has never said he will give us this bill and that's what you take," he said.

So much for that mandate. Polite though it may be, the fight over the stimulus plan is already showing that it may not be as easy for Obama to govern with a Democratic Congress as it is to campaign at the top of a Democratic ticket. Before he's even taken charge, Obama has also gotten pushback from senior Democrats over his choice of Leon Panetta as CIA director (though that dispute seems to have been settled, and Panetta is likely to be confirmed) and rumors that he'll name CNN contributor Sanjay Gupta to be surgeon general.

On Capitol Hill and in Obama's transition office, aides played down any notion of a serious split. "There was what one would probably expect, which was constructive comments," Axelrod said Thursday night, as he squeezed through a crowd of reporters and into an elevator on the second floor of the Capitol. "I'm not going to characterize it as pushback. I characterize it as people doing their jobs." But the incoming administration took the feedback from Congress seriously. Axelrod gave the Democrats a rundown of polling by the Obama team showing the despair that voters feel when they think about the economy, and the transition team dispatched Summers to the Senate again on Sunday. Faced with the prospect of a revolt, the transition team sent a clear message: We're listening. (That alone is a pretty significant change from the Bush administration, which sometimes seemed to be going out of its way to ignore its own Republican allies on the Hill when the GOP controlled Congress.)

Like many other battles over legislation, much of this one is about details, but there may also be a philosophical divide. The real sticking point is that Senate Democrats don't think that the emphasis on cutting taxes will work -- and some of them, echoing economists like Paul Krugman, think $775 billion is "not enough" to get the economy moving again. Reacting to the report that the transition team released Saturday, Krugman said, "This looks like an estimate from the Obama team itself saying ... that the plan would close only around a third of the output gap over the next two years ... Even if I use [their] estimates instead of my own ... this plan looks too weak." That seems to put Obama on the same side as House minority leader John Boehner, who told CBS's "Face the Nation" on Sunday that the stimulus plan needed to "tax less and spend less" to be successful (never mind decades of economic theory that says government spending can help pull the nation out of a recession). Some liberals see the criticism from the left as part of an elaborate Kabuki exercise that will let Obama appear to be balancing both sides of a political dispute, and in the process, kick the stimulus plan up to around $1 trillion.

But a maneuver that complicated might be more than the Obama team -- scrambling to keep the economy from getting worse, while negotiating with the Bush administration over the last multibillion-dollar plan that was supposed to save the economy -- would really attempt to pull off right now. (Not to mention one that would involve considerably more behind-the-scenes choreography than Senate leaders have shown themselves able to manage recently.) Obama seems to be genuinely open to whatever he needs to do to get a deal done. "You're assuming that I expected it to be easy," he told a reporter Friday, asked whether the stimulus plan was turning out to be more difficult than he thought it would be. "Just show me. If you can show me that something is going to work, I will welcome it. If it works better than something I have proposed, I'll welcome it." (He also said, "If Paul Krugman has a good idea, in terms of how to spend the money, then we're going to do it.") On Sunday, he told ABC's "This Week" that "we're trying to set a tone ... that, you know, Congress is a coequal branch of government. We're not trying to jam anything down people's throats." If he's got to go to these lengths to work with his own party, the 111th Congress may not turn out to be as friendly a place for the Obama administration as Democrats thought a few months ago.

Shares