I'm back -- happy 2011! My big New Year's resolution is to write my book. That leads to smaller resolutions, like trying to ignore most of Sarah Palin's Facebook posts and other right-wing faux-outrages (I promise to write about real outrages) and focus instead on how we got here, two years after the glory of the Obama inauguration, preparing for House Speaker John Boehner.

Working on the book has me obsessed with what happened from the late 1970s through today, when wages began to fall for working-class families and the share of wealth and income going to the top 1 percent of Americans began to skyrocket (it was 8 percent in 1976, now it's almost a quarter, and they control more wealth than the bottom 95 percent). I keep stumbling on -- and writing about -- great work that examines the same era: Jefferson Cowie's "Stayin' Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class," which detailed the cracks in the labor movement that opened up in the '70s (and mostly swallowed unionism in our time), and "Winner Take All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer -- and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class," by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson, the book you have to read to understand how the era's massive political shifts, especially the Democratic Party's tilt to the wealthy, created the dangerous economic inequality that exists today.

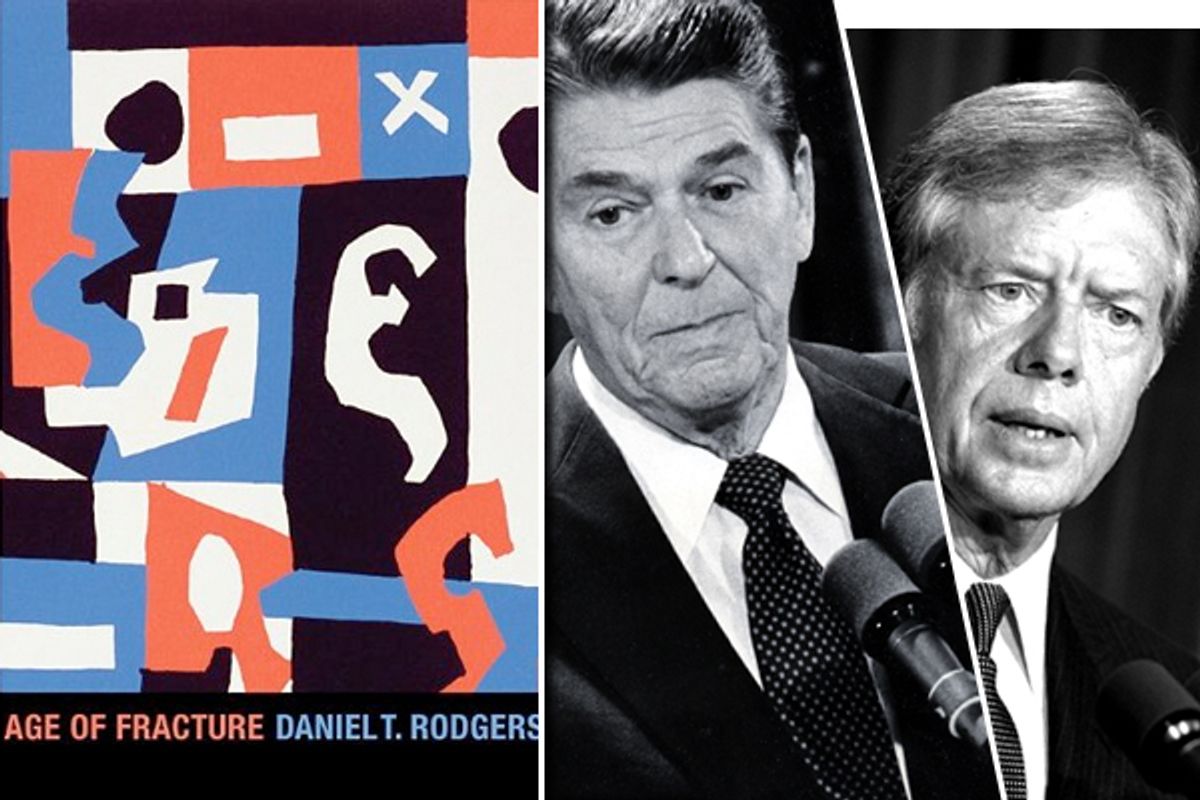

Now comes Daniel T. Rodgers' "Age of Fracture," to explore the cultural and intellectual changes that abetted the political and economic transformations that define our world today. Although Rodgers only mentions the dramatically altered economy occasionally, it occupies his mind: Fundamentally, he's looking at how the political, economic and intellectual theories that gave us the New Deal and Great Society, with their notions of common good and common ground, gave way to ideology and rhetoric that's all about markets and individual freedom -- on the right, of course, but also on the left.

The right-wing side of the story is reasonably well understood; there's a little bit of overlap between Rodgers' book and "Winner Take All Politics," as both describe the very deliberate and well-funded pro-business backlash powered by wealthy right-wing funders in the late '70s and '80s. "The only thing that can save the Republican Party ... is a counterintelligentsia," Nixon Treasury Secretary and stockbroker William Simon proclaimed in the late '70s. When he took over the right-wing Olin Foundation, he began to nurture a dense web of writers and social scientists to counter "the dominant socialist-statist-collectivist" orthodoxy" that he believed dominated Washington, universities and the media.

Rodgers explains how those conservative ideas spread and took hold, substituting faith in choice, markets and individual agency for the Keynesian consensus that had dominated politics and economics from the mid-1930s into the late '70s. Even before Ronald Reagan became president, Democrat Jimmy Carter talked about the "limits" of government, insisting "government cannot solve our problems, it can't set our goals, it cannot define our mission." But Carter framed our alternatives in the Cold War language of "challenge," "pain" and "sacrifice." Reagan adapted Carter's message but served it up with optimism. Government was broken, but the answer was simple, intuitive and personal: Markets and individual agency could make everything right again. "You know, there really is something magic about the marketplace when it's free to operate," Reagan said in early 1982. In fact, magical thinking about markets -- Supply creates its own demand! Tax cuts increase government revenue, because the rich will make even more money to tax! -- dominates political and economic policy to this day, as we saw when Democrats were forced to collude in extending the Bush tax cuts as 2010 ended, even as most of them insisted they didn't believe in the economic theory (or rather propaganda; thanks, Bill Simon!) behind them.

While Rodgers' narrative about the right is fascinating, none of it is terribly surprising: Defending the prerogatives of corporations and the wealthy, in new and novel ways, is what conservatives do. "Age of Fracture" provokes by showing that just as conservatives were marshaling their intellectual and philanthropic forces for what New Right gladiator Paul Weyrich called "a war of ideology ... a war of ideas, it's a war about our way of life," liberals and progressives themselves "fractured" instead. They divided not merely into identity-politics caucuses of women, African-Americans, gays and lesbians and other marginalized groups, but subgroups within subgroups inside those caucuses. (With hindsight, the very language of "liberation" seems itself conservative, as we define the term in the modern age, since it appeared to make liberty paramount.) The locus of the power to be fought -- once the bosses, the system, the patriarchy or The Man -- constantly shifted, and whoever the hell he was, he got more powerful. Meanwhile, Rodgers explains, the early optimism of the black power and feminist movements gave way to squabbling and division.

Black unity turned out to be elusive: divisions between men and women; elites, working class and poor; radical and mainstream; African and Caribbean, plus the explosive question of the so-called underclass made a "black agenda" impossible. Comparable fissures of race, class and sexuality divided the women's movement, so that the lesbian feminist theorist Adrienne Rich, whose 1976 "Of Women Born" celebrated newly discovered "forms of primary intensity between and among women," would lament in 1984 that among feminists, "We did not know whom we meant when we said 'we.'" "We" still don't.

Rodgers acknowledges both the long, shameful history of oppression as well as the thrilling cultural and political ferment that fractured the left into separate, sometimes warring mini-caucuses. But the book makes it clear that those fissures left liberalism without the ideology or rhetoric to combat the language of choice, markets and freedom that replaced social responsibility in the Reagan years. In fact, liberals and progressives of the age often adopted similar language and values. We know Carter bashed government, but even liberal hero Ted Kennedy embraced some corporate deregulation, to show progressives were on the side of innovation and entrepreneurship. On education issues, though early school-voucher notions came from Southern conservatives trying to avoid integration, the first actual experiments were backed by liberals. They wanted to get low-income black children out of systems eroded by white flight and disinvestment -- "imperial institutions," progressive historian Michael Katz called them, sclerotic bureaucracies propagating racism -- and we still see the same impulse in the charter school movement, where black and Latino community activists have often joined with free-marketeers to build public-school system alternatives.

Nowhere is the influence of the '70s market revolution more clear than in feminism, where knotty political and psychological issues of sexuality, motherhood and abortion got reduced to the sterile language of "reproductive rights" and "choice," and ultimately social justice came down to making it possible for women to "choose" whether to be careerists or homemakers (ignoring the economic reality that work is not a choice for the vast majority of American women).

As always, I guess, the victims of the "Age of Fracture" were those at the bottom of society, the poor and working class, who happen to be disproportionately women and minorities. The very language of class, which had once promised (if never delivered) solidarity, "was unexpectedly starting to fall apart" on the left, Rodgers writes, thanks to the fissures of race and gender the age exposed. He spends a lot of time on the welfare reform and "underclass" debates, in which the main problem of the welfare poor was said to be welfare itself. Or as Reagan famously put it: "We fought a war on poverty, and poverty won." Not just conservatives but many liberals abandoned the New Deal and Great Society notions that we had a responsibility to help those at the bottom, or that capitalism regularly had casualties whose suffering should be alleviated by government. President Clinton presided over a sweeping bipartisan welfare reform act, but never marshaled political backing for the childcare, health care or social support he and his advisors knew were crucial to helping mothers on welfare enter and stay in the labor market. And today, even with an unemployment rate hovering around 10 percent, leading Republicans like Newt Gingrich and Sarah Palin believe they're on solid political and economic ground suggesting that unemployment benefits coddle the lazy and might even increase unemployment.

"Age of Fracture" acknowledges, and tries to explain, contradiction and paradox. Rodgers notes, for instance, that alongside its language of markets and individualism, the right sometimes co-opted liberal rhetoric about community and collective responsibility, arguing that liberalism and multiculturalism threatened our unity as a nation. Of course that collective vision could only be implemented by the private sector, where morally upright individuals, (male-headed) nuclear families, churches and neighborhood groups voluntarily pulled together. In fact, as Rodgers observes, conservative crusaders for a common American culture rejected and undermined what had been the one main system for transmitting that culture, public education. It was no accident that the U.S. came to spend more on public education, per capita, than any of its industrial rivals by the mid-20th century; it was the primary way to Americanize successive waves of immigrants. In the '80s and '90s, the right also co-opted the left's language of equal rights, traditionally used to advance the interests of women and minorities, to crusade for the rights of white men and oppose affirmative action and other group-based remedies for discrimination, a battle that continues today, and one which the right is winning.

There were a couple of points on which I'm tempted to argue with Rodgers. Based in a university, he may exaggerate the influence of lefty intellectuals who got sidetracked in debates over post-structuralism and deconstruction, with their ever-shifting, inscrutable and politically useless "discourse" about power and subjectivity. And while I've come to believe identity politics was a divisive and costly if necessary detour on the journey toward a just society for everyone -- and I'm not sure we're back on the main road yet -- I sometimes found myself thinking Rodgers overestimates its atomizing effects; activists and do-gooders have continued to work collectively for group and not merely individual advancement, even when they work in narrower racial and ethnic categories. While I'm inserting dutiful parentheticals and disclaimers, I should also note that I took an American cultural history course from Rodgers while he taught at the University of Wisconsin (he's long been at Princeton), and he's one of the five or six professors I remember vividly and with gratitude, though I haven't seen him since the end of the '70s, when, coincidentally, his "age of fracture" begins. Finally, I worry I have no objectivity about "Age of Fracture" because it's my age: I went to college and began my work life in the days of Carter and Reagan, and I have been recovering from all of its cultural contradictions and excesses -- identity politics, post-structuralism, the right's victorious case for free markets and less government, the left's relative intellectual and political impotence -- ever since.

But I -- or may I say we? -- might never recover. The "Age of Fracture" that Rodgers identifies in the last quarter of the 20th century is probably more representative of American history than the age of common ground and unity that preceded it. (Rodgers, by the way, doesn't argue otherwise.) It's clear that the twin traumas of the Great Depression and World War II, followed by the Cold War with the Soviet empire, led American leaders to an unprecedented 40 years of bipartisan near-consensus: that capitalism wasn't perfect, markets always needed correction, and both capitalist dysfunction as well as the threat of communism could be fought by Keynesian economics and investment in expanded opportunity.

It's also clear from this book and others I've read in the last two months, while trying to write a book titled "Indivisible: How Fear-driven Politics Hurts America, and Pulling Together Makes Us Stronger," that we have in fact been quite divisible throughout our history. It's only the existence of grave, usually external threats (abetted by potential internal allies) that has made Americans come together. One of the earliest threats was Catholicism; the religion's loyalty to a foreign and authoritarian power (the Vatican) as well as its communitarian ethos seemed incompatible with Protestant individualism and democracy. But where the influx of Irish and German Catholic immigrants in the mid-19th century led to Nativist violence and Know-Nothing politics, it also inspired early innovations in public education, social welfare and other efforts to Americanize and civilize the threatening newcomers. Later, labor radicalism ignited by robber-baron capitalism and repeated economic crashes, as well as another influx of scary immigrants (this time with socialist traditions, not Catholic ones), helped lead to the reforms of the Progressive era, which laid the groundwork for the labor rights and social programs that would change American politics and culture under FDR's New Deal.

Ultimately, it was the national mobilization required by World War II and the Cold War that built the stunning infrastructure of security and prosperity that most people who are over 40 came to see as the American norm: a vast web of expanded education spending, home-ownership opportunities, transportation initiatives, social-welfare programs and environmental protection, which reached an apex not with Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, but under Richard Nixon. What followed was the political, economic and cultural unraveling charted in "Age of Fracture," and we still don't know what, if anything, will galvanize another age of unity, however temporary.

I came to the end of "Age of Fracture" with the same feeling I had finishing "Stayin' Alive" and "Winner Take All Politics:" Now what? "Age of Fracture" is even more of a cliff-hanger, because its epilogue shows how our new national ideology of markets and freedom, and our lack of faith in any kind of larger collective endeavor, persisted, disastrously, through the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama (so far, anyway), despite their political differences. It only reinforced the sense of frustration and even fear I've described watching the economic half-measures pursued by the Obama administration in the last two years. Rahm Emanuel enraged Republicans by quipping "You never want a serious crisis to go to waste" to push Obama's agenda in early 2009. But in fact, the White House may have done just that; the Bush White House certainly did. The assault of 9/11 and the larger threat posed by violent Islamic radicalism, followed by the bank meltdown and economic crash of 2008, was exactly the kind of foreign and domestic crisis that in the past combined to heal American fractures and lead to ages of progress. Instead, it looks to have been wasted.

Bush squandered the spirit of patriotism, unity and sacrifice inspired by the 9/11 attacks with an unnecessary war with Iraq and calls for Americans to heal their nation by being good consumers. ("Restaurants are part of who we are as Americans," the American Restaurant Association advertised, as Rodgers reminds us.) The triumph of GOP market essentialism meant he couldn't pay for the war with tax hikes (or, heaven forbid, a draft). So it had to be done on the cheap – and of course it could be, because once you liberate individuals to grab their liberty, you have a great new society, just like we do today. Right? One of the (darkly) funniest parts of Rodgers' book is when he quotes Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Bremer talking about Iraqis exactly the way conservative anti-welfare reformers talked about the American poor a decade or two earlier: Too much American assistance was "unnatural" and would create "dependency," Rumsfeld argued, while Bremer insisted: "We don't owe the people of Iraq anything. We're giving them their freedom. That's enough."

Of course it will take more than freedom to rebuild Iraqi society, and our own. "Age of Fracture" made me think about the discredited metaphor of the American "melting pot," which has yet to be replaced. It wasn't just progressives, or non-white racial groups, who objected to the notion they had to lose their identity (in some kind of scorching 19th-century process that, when you think about it, seems unappetizing, possibly disgusting and maybe even painful) -- Rodgers reminded me of Michael Novak's 1972 "The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics," about white ethnic working-class folks who were feeling left out by other liberation movements and the so-called Great Society. The rejection of a single American vision or project, of an American people in favor of "peoples," was understandable, given the cruelty and contradictions of American history, but not without cost. The nation, not just the left, badly fractured in the last 30 years, and all but the wealthiest Americans are paying some kind of price. Unfortunately, we still haven't produced the ideas or ideals that will make Americans come together, and feel ready to take a chance on each other, once again.

Shares