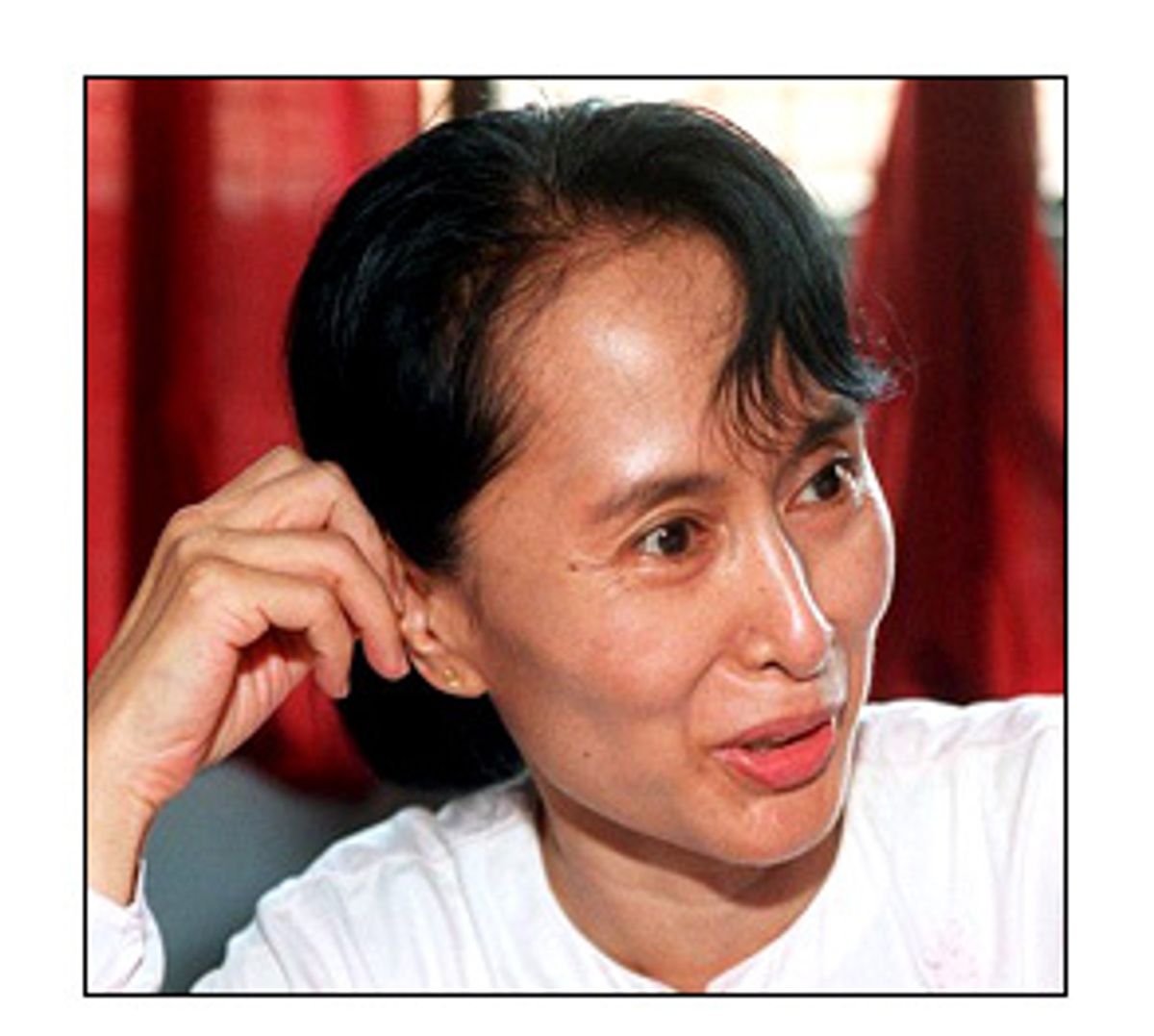

A question that has to haunt anyone pondering the predicament of Burma's democratic resistance leader Aung San Suu Kyi is: Why hasn't she been killed? She is, after all, a major thorn in the sides of the military dictators who have been driving the Southeast Asian nation to ruin for the past 38 years. Certainly she would not be the first popular opposition leader to be murdered by despots.

The simple answer is they missed their chance. Suu Kyi (pronounced soo chee), 55, was first confined to house arrest in 1989, months before her National League of Democracy won Burma's last election in a landslide. The dictators ignored the election results and proceeded to arrest all the NLD leaders they hadn't already jailed previously, and continued the kind of repression that had been the junta's modus operandi since 1962. But in 1991 something happened that the dictators couldn't have anticipated. Suu Kyi won the Nobel Peace Prize. The eyes of the world suddenly became focused on this slight, Buddhist woman locked in her home, forbidden from picking up her award. But her captors came under international gaze as well, and killing Suu Kyi now would be too reckless a move even for a junta that makes murder and slavery cornerstones of its policy.

The Burmese dictatorship is known within and outside the country as SLORC, for State Law and Order Restoration Council, the banner under which the autocrats ran in the 1990 elections they conveniently dismissed. Three years ago they changed their name to the even more Orwellian State Peace and Development Council, but SLORC seems to fit them better. In the manner of many dictatorships, SLORC is fond of renaming. In 1988 SLORC decided to call Burma "Myanmar," but most of the world, recognizing the illegitimacy of the government, ignores the name change, much in the way "Kampuchea" is now nothing more than a synonym for the evil visited on Cambodia by Pol Pot and his minions.

Under SLORC's reign, Burma has vied with a few other countries, such as North Korea, Afghanistan and Algeria, for the honor of serving as poster child for a nation destroyed by tyrants. By any objective measure Burma -- as physically beautiful and as rich in natural resources as any Southeast Asian country -- is in dire straits. It was ranked second to last, after Sierra Leone, on healthcare spending per capita, according to the World Health Organization. The result is that diseases (including AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and anthrax) are rampant. AIDS is considered more epidemic in Burma than in Thailand, on a par with the scourge in southern Africa. Contributing to the problem is a robust drug trade: Burma alternates with Afghanistan as the largest heroin producer in the world, and burgeoning drug addiction within Burma is helping to spread AIDS.

The Burmese armed forces are thought to be about 500,000 strong and are ruthless in enforcing SLORC's will. Forced relocation is common, with entire communities uprooted and moved to slums or barren lands where they are barely able to survive. SLORC uses slave labor for construction projects, including children, and Amnesty International reports that thousands of Burmese are kidnapped each year and made to carry supplies for the army through dense, mountainous jungle, where ethnic resistance groups reside.

The Burmese economy is in shambles. People earn less than a dollar a day, and many are illiterate because SLORC has closed down hundreds of schools. The United Nations reports that Burma spends 28 cents a year per student on public schools. Four out of 10 children are reported to be malnourished, and the average life expectancy for Burmese is less than 50 years. SLORC is paranoid about people congregating, and gatherings of more than four people are forbidden. Unions, needless to say, are prohibited, and SLORC owns all the media. It's illegal to possess a home computer. Anyone who violates SLORC's capricious laws is subject to lengthy prison sentences and torture, which, according to Amnesty International, is a specialty of the junta.

In 1995, Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., visited Burma while on a fact-finding mission in Southeast Asia. Newsweek reported that Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt of SLORC welcomed McCain by screening for him a video of machete-wielding thugs beheading Burmese villagers. McCain later said of the junta members, "These are very bad people."

Yet despite the horror, hope lives on in Burma, and much of it rides on Aung San Suu Kyi. It's a lot for one person to bear, but Suu Kyi seems born to the task -- literally and constitutionally. Not only is she the daughter of Aung San -- considered the father of Burmese democracy and an assassinated martyr to the cause of freedom -- and as such revered almost automatically, but her deep Buddhist training has made her uniquely fit to weather a life of confinement and isolation. She meditates daily, a discipline that provides insight into life beyond the external reality most of us perceive, and she hews strictly to Buddhist proscriptions against harming, hate, fear and ego.

In a 1995 interview with Alan Clements, an American author who lived as a Buddhist monk in Burma for several years and who wrote the 1992 book "Burma: The Next Killing Fields?" Suu Kyi alluded to another interviewer who kept asking if she really was not frightened. "Why should I have been frightened?" she said. "I'm not sure a Buddhist would have asked this question. Buddhists in general would have understood that isolation is not something to be frightened of." Then she added, "You cannot really be frightened of people you do not hate. Hate and fear go hand in hand."

Buddhism aside, Suu Kyi's commitment to Burma's freedom is bedrock, and this also anchors her. At every opportunity presented she reiterates the demand that SLORC must yield to the election results of 1990 and make the country democratic. Her steadfastness has led to some almost comical situations. In 1998, during one of the rare periods SLORC released her from house arrest -- but still prohibited her from traveling outside the capital -- she attempted to leave town to meet with another NLD official. When soldiers blocked her way she refused to turn back and ended up camping out in her car for six days before she was forcibly returned home. She tried it again, she was taken home again and right away she vowed to make another attempt, asserting that she was not "legally restricted in any way." Finally SLORC reimposed house arrest.

Suu Kyi's father was born in 1915, when Burma was a colony of Britain. A devout Buddhist, Aung San became a leader in Burma's struggle for independence. During World War II, he believed that Japan would be the route to Burma's freedom, and he fought with the Japanese when they invaded the country. But when they proved to be even more despotic than the British, Aung San and his compatriots switched sides and fought with the British to expel the Japanese. At the end of the war, Britain and Burma worked together to set up a parliamentary structure so that the Burmese could take control of their country. Aung San's party swept the elections, but only months later, in 1947, he and several members of his government were shot dead by political rivals. Soon after that, Burma descended into a civil war among ethnic groups.

Suu Kyi was 2 at the time of her father's death. Her mother, Khin Kyi, was a vital figure in the early years of Burma's independence, serving in several government capacities. In 1960 Khin Kyi was appointed ambassador to India, moving to New Delhi with her daughter and two sons. While Suu Kyi got a good British high school education, her mother made sure that her daughter did not stray from the Buddhist path. Suu Kyi was a voracious reader and had a particular fascination with Mahatma Gandhi. In 1964, Suu Kyi enrolled at Oxford, getting degrees in philosophy and economics in 1967.

In the 1991 Nobel Prize Annual, Irwin Abrams sketched a bit of biography from Suu Kyi's time at Oxford. "The diminutive beauty from Burma was a striking figure. Her close friend of those days, Ann Pasternak Slater, remembers how her 'tight, trim lungi (the Burmese version of the sarong) and her upright carriage, her firm moral convictions and inherited social grace contrasted sharply' with the casual manners and ill-defined moral standards of the English students.

"Slater recalls [Suu Kyi's] curiosity about Western ways. Despite Buddhist injunctions, she took one little sip of an alcoholic drink just to find out what it was like -- and didn't like it. And so that she could know the experience of other woman students, who returned from late dates after the gates were locked and had to climb over the garden wall of their dormitory to get in, she had a friend from India bring her back from a dinner date at midnight, so he could help her over the wall. Slater also remembers the characteristic determination with which Suu Kyi learned to bicycle in her lungi."

After graduating from Oxford, Suu Kyi moved to New York, where she worked for the United Nations secretariat and volunteered as a social worker at a New York hospital. In 1972 she married Michael Aris, a scholar of Asian literature and history. While Aris studied in England, they had two sons, Alexander and Kim. Suu Kyi taught Burmese studies at Oxford while doing postgraduate research in her country's history. The family returned frequently to Burma to spend time with Khin Kyi, who was retired in her Rangoon home.

Things were not going well in Burma. For years the democratic government had tried to maintain control during civil war, but a junta led by Gen. Ne Win took over in 1958, and consolidated power in 1962. He abolished the constitution, banned all political parties, nationalized many businesses, installed military personnel in government positions and announced he was leading Burma down the "socialist path." The downward spiral had begun.

As economic and social conditions unraveled under the inept dictator's mismanagement, civil unrest began to erupt in the '80s. Students organized and held rallies demanding restoration of democracy and human rights. On Aug. 8, 1988, a massive general strike and demonstration were declared. Ne Win responded by calling out the troops. Over the next several days, soldiers fired on crowds, killing between 1,000 and 10,000 civilians. Still, the demonstrations continued, and the government actually seemed to back down. But then a new set of generals, calling themselves SLORC, asserted that they were in control, and ratcheted up the repression further.

Coincident with all this, Suu Kyi was in Rangoon, caring for her mother (who had suffered a stroke) and watching the tumult from the sidelines. After the massacres, she decided to take action. Speaking to a huge crowd under a poster of her father, she said, "I could not, as my father's daughter, remain indifferent to all that was going on." With her simple and direct demands for civil rights and her insistence on nonviolent resistance, she won over thousands of Burmese and became the country's avatar of democracy.

Meanwhile, SLORC surprised everyone by announcing that a "free and fair" election would be held in 1989, open to all parties. More than 200 parties registered to run, but the NLD, thanks to Suu Kyi's participation, drew the most support. The organization was also one of the few that had the courage to defy an SLORC ban on public assembly, an edict that effectively precluded anyone from campaigning. Not only that, SLORC insisted on vetting all public documents issued by political parties. Suu Kyi, the NLD's nominal leader, simply refused to accede to any of SLORC's demands. She continued to campaign around the country, facing phalanxes of armed guards everywhere she spoke.

In one famous incident, Suu Kyi and fellow NLD members were on the campaign trail when they found themselves staring into the rifle barrels of a squadron of soldiers. An SLORC officer seemed prepared to give the order to fire, when Suu Kyi motioned her colleagues away and walked straight toward the officer, staring him down. He ordered the troops to withdraw. "It seemed so much simpler to provide them with a single target than to bring everyone else in," she said afterward.

SLORC finally ordered Suu Kyi into house arrest, and rounded up most of the other NLD leaders, sentencing several to years in prison. Many were tortured. But then came the real shocker for SLORC: In the election held in May 1990 the NLD won 392 seats in the National Assembly, compared with 10 for SLORC. Far from transferring power, SLORC responded with wave after wave of terror. Still, Suu Kyi would not be silenced. At first SLORC permitted her visits from her husband and sons, and she was able to get her writings out to the world through them. But in the fall of '90 the junta forbade all visits, not even letting her get mail. SLORC tried to play the family card, encouraging her to visit Aris and the boys in England, but she refused, knowing she'd be barred from Burma for good.

In 1995 SLORC relaxed restrictions on her, and she was able to receive visitors, including several interviewers. She described her daily routine to a reporter for Asia TV: "I get up at 4:30 in the morning. I meditate for an hour. Then I listen to the BBC world service, then I listen to the VOA [Voice of America] news in Burmese, and then the BBC news in Burmese. If I could hear it, I would listen to the Democratic Voice of Burma, but that is not always very clear. Then of course I take a bath, have breakfast and then the rest of the day I divide into periods for reading, for walking around the house and for playing a bit of music."

Were it not for the radio, she said, she would not have known she won the Nobel Prize.

In her interview with Clements, Suu Kyi elaborated on her attitude toward her captors in answer to his question, "You have been at the physical mercy of the authorities ever since you entered your people's struggle for democracy. But has the SLORC ever captured you inside emotionally or mentally?"

No, and I think this is because I have never learned to hate them. If I had, I would have really been at their mercy. Have you read a book called "Middlemarch" by George Eliot? There was a character called Dr. Lydgate, whose marriage turned out to be a disappointment. I remember a remark about him, something to the effect that what he was afraid of was that he might no longer be able to love his wife who had been a disappointment to him. When I first read this remark, I found it rather puzzling. It shows that I was very immature at that time. My attitude was -- shouldn't he have been more afraid that she might have stopped loving him? But now I understand why he felt like that. If he had stopped loving his wife, he would have been entirely defeated. His whole life would have been a disappointment. But what she did and how she felt was something quite different. I've always felt that, if I had really started hating my captors, hating the SLORC and the army, I would have defeated myself.

However, in a Vanity Fair article from 1995 she detailed her tribulations: "'Sometimes I didn't even have enough money to eat,' she went on. 'I became so weak from malnourishment that my hair fell out, and I couldn't get out of bed. I was afraid that I had damaged my heart. Every time I moved, my heart went thump-thump-thump, and it was hard to breathe. I fell to nearly 90 pounds from my normal 106. I thought to myself that I'd die of heart failure, not starvation at all. Then my eyes started to go bad. I developed spondylitis, which is a degeneration of the spinal column.' She paused for a moment, then pointed with a finger to her head and said, 'But they never got me up here.'"

She didn't lose her sense of humor, either. When Clements asked her if her phone was tapped, she said, "Oh, yes, probably. If it is not I would have to accuse them of inefficiency. I would have to complain to Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt [SLORC's military intelligence chief] and say, 'Your people are really not doing their job properly.'"

SLORC granted Suu Kyi some freedom of movement in 1995, but that didn't extend to meeting with NLD colleagues. Worse, SLORC wouldn't let her family into the country for visits, even when her husband was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1998. He was denied a visa to visit Suu Kyi a final time in 1999 and died in London. The generals hoped she would attend the funeral, but she knew the realities. She said simply, "I feel so fortunate to have had such a wonderful husband who has always given me the understanding I needed; nothing can take that away from me."

And nothing, it seems, can take Suu Kyi away from the SLORC generals. Restrict her movement as they will, she goes on, making speeches, handing out food to the poor, issuing papers and making it clear that democratic aspirations in Burma live on. She will not stand down. And here's something about the psychology of the totalitarian mind -- the dictators must understand that Suu Kyi is good for them as well, because as long as they let her live, the international community can say, "Look, the government's not so bad; they keep that woman around." She's SLORC's trump card.

So now there is communication. For the past four months SLORC agents have been meeting with Suu Kyi regularly while reportedly releasing NLD members from prison. The content of their meetings has not been reported, and whether they have any real significance is impossible to know right now, but it's hard to imagine SLORC ceding any real power. Yet we can hope. If Vaclav Havel and Nelson Mandela could emerge from lengthy prison sentences to lead their countries in freedom, perhaps Suu Kyi will get a turn.

Shares