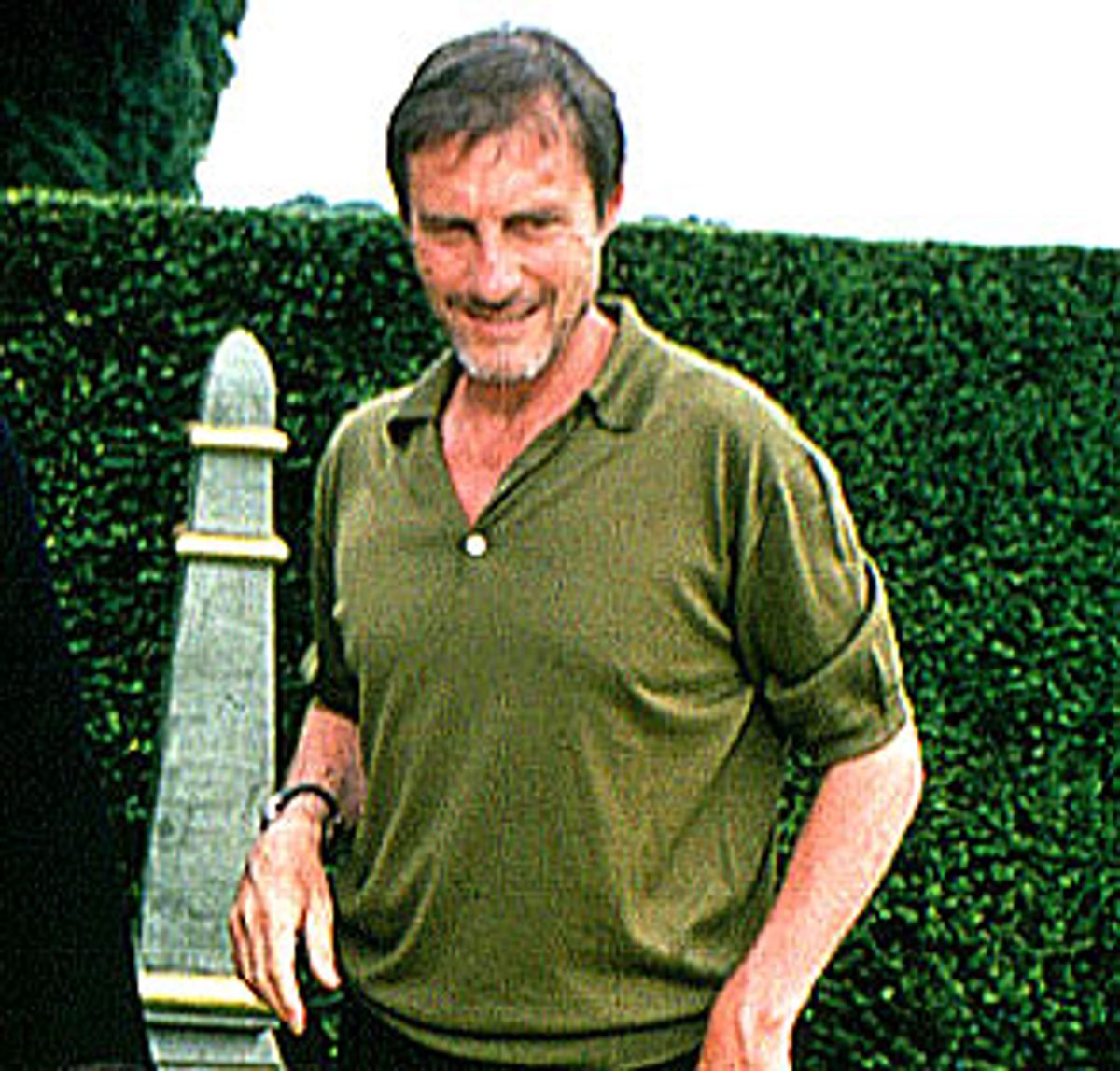

Gaunt, bearded and slightly disheveled, Roland Joffé looks as out of place in this trendy Hollywood restaurant as George W. Bush behind the lectern at a White House news conference. There's something a little too sensitive about Joffé, as if he can't really get with La-La Land's hip viciousness. That's a genuine handicap for him. Minus the epidermis of a rhino, he might as well be back where his career began, shooting for British TV. Not that there aren't worse fates, mind you.

One worse fate would be to remain one of the critics' favorite human piqatas. That's a role the 55-year-old Joffé has had since he made such an impact in the '80s with "The Mission" and "The Killing Fields," two of the most acclaimed films of that decade. A brilliant, brutal tale of the Khmer Rouge's Cambodian holocaust, "The Killing Fields" took three Academy Awards in 1985 for best cinematography, best film editing and best supporting actor for Haing Ngor. "The Mission," Joffé's tragic tale of an 18th century Catholic mission in South America, netted a Oscar in 1987 for best cinematography in addition to the 1986 Palm d'Or at Cannes.

Joffé's subsequent films have mostly garnered raspberries. In particular, "The Scarlet Letter," starring Demi Moore and Gary Oldman as Hawthorne's favorite adulterers, provoked film scribes to pull out their literary Ginsu knives and slice up Joffé like a Hickory Farms smoked sausage. And affixing his name to MTV's popular sleaze-tease soap opera "Undressed" as executive producer hasn't exactly polished his rep with the scribblers. (Though it may have helped with studio brass.) No wonder he looks a bit gun-shy as we meet to discuss his latest film, "Vatel," an opulent $37 million re-creation of a weekend of frivolity and intrigue in the court of Louis XIV.

The film features Gerard Depardieu as renowned French steward and cook Francois Vatel. It's Vatel's task to please the mercurial, manipulative Sun King (Julian Sands) while avoiding the machinations of the monarch's cunning aide, the Marquis de Lauzun (Tim Roth in full "Rob Roy" mode) and winning the heart of Uma Thurman's Anne de Montausier, one of Louis XIV's ample-bosomed courtesans. "Vatel" is in the running for an Academy Award for best art direction after being released briefly late last year for Oscar consideration. It's being re-released today, and so far the reviews are mixed. Still, that's better than the perpetual flogging Joffé's been used to of late. So as "Vatel" heads for the theaters, he may finally have reason to hope that his fortunes are on the upswing.

In "Vatel," the title character must entertain an elite crowd with food and pageantry, yet despite his talent and hard work, he feels that his efforts are never enough to satisfy those he's serving. Is there some parallel there to your own position in the world of cinema?

Absolutely. When I read the first draft of the screenplay, I thought, "My God, this is about being a director." In some ways you're God. In other ways you're just a servant. You're a travel agent for the actors, saying, "No, you can't have Thursdays off," and, "I don't think a flight to Madrid is a great idea just now." You're dealing with their tantrums, their whims. And you're serving the studios, and their money. That role reversal is fascinating. Vatel and I are similar in other ways. I have a drive to tell stories like Vatel has a drive to cook.

What happens when that drive to tell stories becomes a commodity?

You get into very strange psychological territory. Other people are applying a value to what you're doing for their own purposes. Then your value systems start shifting. You're in constant confrontation with your personality. The drive to serve the king of France, or the public, or the studio is not quite the same as the drive to make great food or a great movie. There's a split, and you have to struggle between those two. I don't know whether I do it well or badly, but the struggle is real.

There's a terrific scene in the movie where Vatel's fate is decided by a card game. Have you ever felt that your future is being decided in such a manner?

Totally. It's not only your future, it's your ability to express yourself. Vatel doesn't want to go to the court because he doesn't want to be in that world. He knows the price of it. Tim Roth's character, the Marquis de Lauzun, lives in that world -- he's a realist. Uma Thurman's character, Anne de Monstausier, is like a neophyte celebrity. She's got one foot in it, and is just beginning to understand what's up, which is why she's drawn to Vatel. She's caught between Lauzun and Vatel, and that's her dilemma. That's the dilemma of any actress in Hollywood. Look how cruel Hollywood can be to actresses. Her career can be over in 30 seconds. It's very like a card game. I've heard people say, "So-and-so is finished." I'll say, "But she's a great actress." And they say, "No, she's finished." You don't know why the door closed on them. It just did.

Louis XIV made his court like that. That's why I thought it the perfect paradigm for our world. When Louis took over the throne, he was 14 and there was this big civil war. He learned very early on that force of arms was not going to unify France. He knew he had to control the purse strings and not worry about his military's hold over the nobility. He pushed the bourgeoisie forward, and introduced the notion that one could advance by right of wit rather than right of birth. He created an environment of great instability where the only sure way to survive was to have enough money, or the eye of the king.

Vatel's escape from this predicament is a morbid one. How do you emerge from a similar dilemma without it ending badly?

In all fairness to Vatel, I'm probably more like Uma's character, Anne. I wish I had the nobility of Vatel, but I've got the confusions that Anne's got. I don't have Vatel's strength of character, that simplicity and greatness. I'm more like Anne because I'm between those two elements -- the virtuous and the venal. That's where I live. I wouldn't be alive if I didn't have that dilemma.

How did you choose the principal players for this film? Did you have Depardieu in mind from the beginning?

Pretty much. I didn't want Vatel to be too much of an aesthete. I wanted a working-class element to him -- with big hands, face and neck. Gerard has all that. As for Uma, I thought she would understand Anne's dilemma of being stuck between being a public and a private figure. With Tim, he has an amazing ability to present men of extreme Machiavellian qualities who are not evil. Lauzun, his character, would be running a Hollywood studio in our age.

Did you do anything special to get the actors to inhabit their characters rather than just those baroque getups they wore?

I wrote each of them letters or memoirs, which I said I'd found in the museum. I had them printed up rather neatly, bound in little books and given to them. I wrote them all in the first person from my research, and they were written with a slight bias toward the scenes they had to play.

Also, when we constructed the costumes, I had them made like pop star costumes. I wouldn't allow the costume designer to use the material she'd normally use. I took her to a shop in Paris that makes clothes for pop stars, and there were all these iridescent, shiny clothes. I said, "Here's the court. It was a court of pop stars. Every person in that court spent everything they could on what they wore." I got the actors into them very early, and gave them exactly the same spiel. When they were fitted, we'd have pop music going so they'd have that in their heads. I'd talk to them about Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, to give them a sense of how they should act.

About Vatel's feasts and spectacles, how close were your screen versions to the historical ones?

Ours were inspired by research, though designed with our own agenda in mind. Like the trees that spring from boxes, that was something I worked with the designer on. I took the designer to a garden and said, "I'll be Vatel, you be Vatel's assistant and I'll tell you what I want to create for the king." I told him, "The point of being the king is to make everything fertile, to make the country work. Therefore you come to a bare alley, and once the music starts, all these flowers sprout from nowhere and trees jump out of boxes. It should be like a child's pop-up book. Within 30 seconds, the king finds himself in a kind of enchanted garden with the whole court applauding." That's how the idea came. We worked it out from there.

How about those fireworks displays at their dinners, and the ornately carved ice sculptures -- did they actually have those back then?

Fireworks came from China at the time. They didn't have fireworks at their banquet tables -- that was my idea. They could have done it, but they'd probably have set themselves on fire. They did have ice sculptures, though. They'd pack snow in the winter, in pits in the ground, and it just became solid as rock. Then they go and cut the ice out of these holes about 15 feet down, take it out and wrap it in straw. That would last about three days.

"Vatel" is up for an Academy Award for art direction. You've had films nominated before. How does it feel this time?

Thrilling. This round was the most important in a way because it was designers who picked the movie, and they know. Now we go to another phase, which is like the court, where the academy picks the winner. At that point, it's a popularity contest. Quite often things do clean sweeps for no discernible reason. So I'm guarded.

Going into a project, do you know that you're going to end up with something really special, like "The Mission" or "The Killing Fields"?

I don't think anyone ever really knows. You make the film with all the terror and panic of somebody going to war. You hope you're going to come out the other side, but nothing's certain. You just have to tell your story with as much purity as you can, if you love it. I think of someone like John Ford, who made scores of films, and I remember like four or five. That's pretty magnificent, really, when you think of it. Directors have problems today because it takes so long to get a movie together. You can't make 50 movies the way things work now.

Is that a goal for you, to leave behind a handful of classics?

I'd be pretentious if I felt that's what I wanted to do. Would I be enchanted if that happens? Yes, I would. But the drive to make a movie is the whole process, in a way. You're doing it because you want to tell a story or because you learn things.

Like what?

Well, when I was doing research for "Fat Man and Little Boy," I spoke to scientists who worked on the atomic bomb. There was one scientist whom I asked, "How could you have possibly thought that there would not be a radioactive effect from the dropping of the bomb?" His eyes watered slightly, and he said, "I can't answer that question, but I can point you in the right direction." He told me to look up the medical records of this research laboratory from 1943-45. I got access to them through the Freedom of Information Act. I found they had been injecting plutonium into mentally handicapped patients. This had never been published before. So I put that in the film, and it caused quite a stir. That's one example.

Do you think critics have a tendency to make snap judgments when they see things like that, that don't jibe with their preconceived notions?

Because critics are writing quickly, they have a tendency to believe their prejudices are true. For instance, about "Fat Man and Little Boy," one critic said, "This is ridiculous, all of these scientists look like kids." But the average age at Los Alamos was 24. So instead of saying, "Oh, we didn't know, isn't that interesting," they say, "Isn't this ridiculous." But it's based on nothing. When I did "City of Joy," people would say, "Well, Calcutta isn't like that. All these houses are painted different colors." But they'd never been to Calcutta, which they think is like those black-and-white photographs of starving children with their bellies stuck out. It's not like that. Calcutta's extremely colorful. There is no more color to be found than in one of those Calcutta slums.

In reading reviews of your work, have you ever found what you believe to be valid criticisms, criticisms that have caused you to reassess how you shot a film?

I don't think so, because the reviews very rarely attack the filmmaking. I don't think I've ever read a review that claimed, "This man doesn't know how to make a film." Well, there was one, in the Village Voice back when "The Killing Fields" was released, which said, "There are two movies coming out this week. One is 'Sheena: Queen of the Jungle,' and the other is 'The Killing Fields.' Go and see 'Sheena: Queen of the Jungle'; 'The Killing Fields' is quite simply the worst movie ever made."

That's funny. When I was looking back over some of the old reviews of your films, I just assumed everyone would've been in awe of "The Killing Fields" and "The Mission." But actually, there were a number of critics who didn't care for either.

True. But that can be said of every filmmaker, like if you're looking back over all Kubrick's films and their notices. Often very good films create that sort of reaction, especially those that have broken the mold.

Does what the critics say ever wound you? They can be pretty cruel at times.

Of course, but that's part of the game. If you stick your head above the parapet, you can't expect people not to throw things at you. My personal hurt doesn't worry me too much. But I worry career-wise. Because if this unremitting wall of disdain doesn't collapse, I won't be able to go on making movies. You feel strangled. You see so many movies going out which are hailed as great, but you know that 10 minutes later nobody's going to remember them. It's disheartening.

There are a handful of films out now that are set in France, but shot in English, like "Chocolat," "Quills" and your film. I know you spend a lot of time in France. How do the French react to these pictures?

It makes them furious, and they're none too happy with Gerard Depardieu. They say things like, "What does he think he's doing?" and "When I see Louis XIV speaking English, it makes me livid." That sort of thing. I knew that would happen. But the only way we'd get the money was to shoot in English. I didn't feel there was any betrayal at all. Julian Sands' portrayal of Louis XIV is pointedly accurate, for instance.

What's next for you?

I don't know. I'm kind of looking at doing a thriller. I think I can do one rather well. Of course, that's if I can persuade any executives of that. That's what it comes down to. You can understand it, though. The politics of the studio, like the politics of court, are rife with self-interest. They have to be.

Shares