Ken Nordine has made his way through this world with his voice. He has made a good living by pitching paint, jeans, coffee and cars. And he has made a fascinating life with something he invented called "Word Jazz." Originally the title of his seminal 1957 album, the term now designates a genre. And if you know the right people, dropping that term elicits a conspiratorial grin.

Nordine, who's lived in Chicago all his life, is in the enviable position of being respected for both his commercial and artistic work. His phone is as likely to ring with an invitation from Laurie Anderson as with a voice-over offer from Chrysler-Plymouth. His artistic collaborations have found him head to head with Tom Waits, Brian Eno, Smokey Robinson and Jerry Garcia.

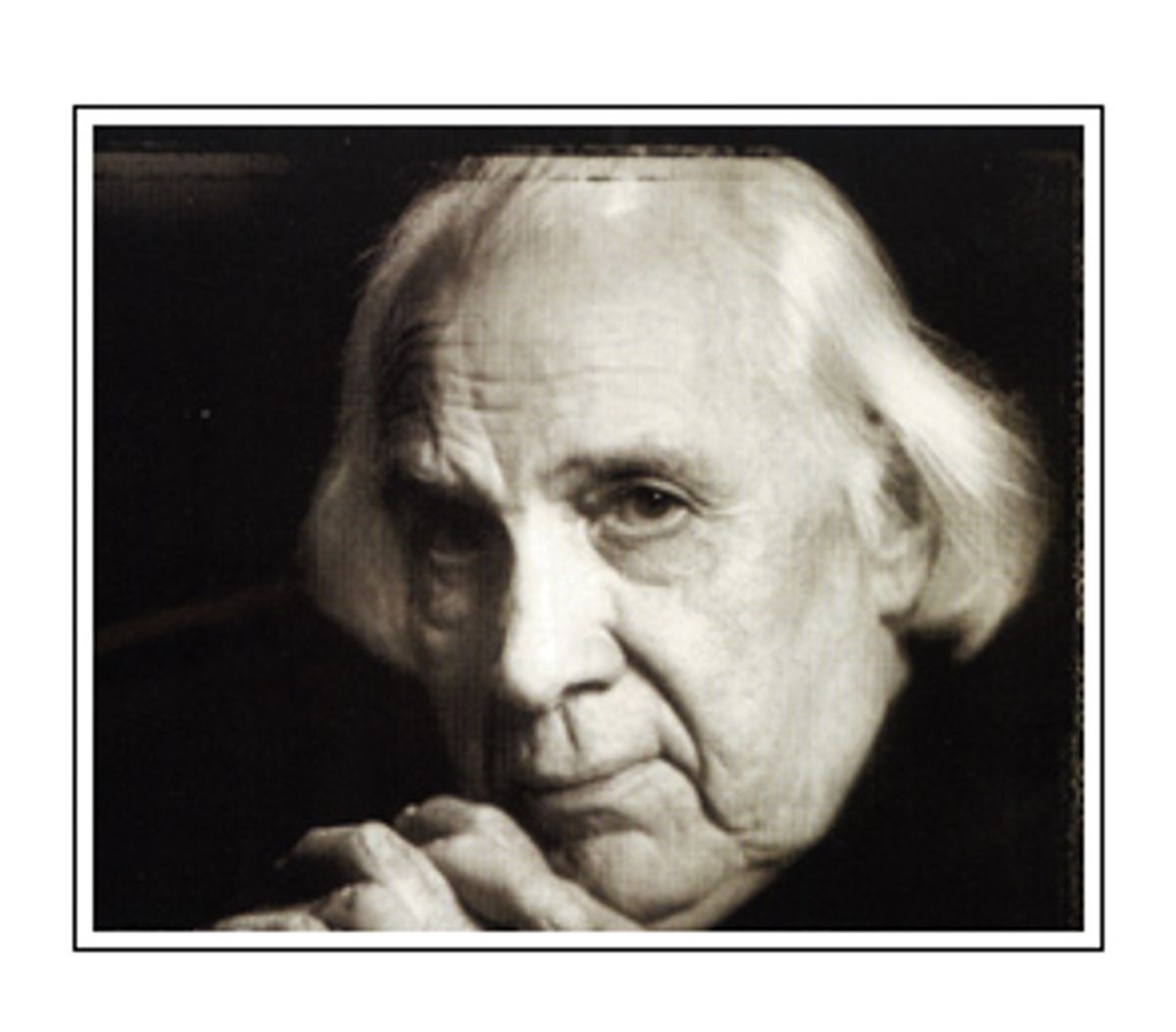

Nordine's latest CD, "A Transparent Mask," was recently released by Asphodel Records. Attempting to describe it is a delightful and impossible task. Start with the voice. Not just a voice but The Voice. Nordine, now 81 years old (and still vocally blessed), claims his voice is a gift from God -- which one he does not say, but it is a voice that any god would envy. Single adjectives like deep, dark and rich are anemic, shallow and inadequate means of description. The voice is a one-off secret blending whose ingredients we can only guess at. A crude attempt at reverse engineering might reveal the hypnagogic tones of Franz Mesmer and the cathedral crypt timbres of Orson Welles, Barry White or Lord Buckley. We would also find a handful of charcoal, a dollop of urban 3 a.m., the subsonics of Poe's "Tell Tale Heart," Tom Waits' bass growl buff shined with diamond dust and a pinch of Nordinium (the rarest of all the hip and heavy elements).

Nordine's voice and mind are employed to dazzling effect on the 20 tracks of "A Transparent Mask." Some cuts approach linear story telling, some are tethered so tenuously that just the thought of a pair of scissors would set them free, while others unapologetically shoot straight for Mars with not even a casual nod towards Houston.

Nordine's topics range far and wide. The opening track, "As of Now," is based on the writings of the second century Roman philosopher and emperor Marcus Aurelius. In "The Akond of Swat," he blasts away at the world of a Middle Eastern despot by utilizing the text of the pioneering 19th-century nonsense writer Edward Lear. And in "You Were So Crazy," Nordine comes as close as anyone ever will to anthropomorphizing a cello.

I spoke with him on June 11 at about 11 a.m. Pacific Daylight time. Timothy McVeigh was only hours dead, and the execution was the first thing on Nordine's mind.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I had a spooky morning, you know, with the McVeigh execution. It was a very strange feeling I had about it because almost 50 years ago I actually filmed the poem "Invictus" [the poem that McVeigh submitted in writing as his final statement] but I did it as sort of a satire in a barbershop at the Ambassador West Hotel. I rented the barbershop for the whole day. And there was a manicurist and a black guy who, you know, did the shoe shining, way back then. And there I was sitting with the sheet over me with a scotch in the right hand. It was a voice-over kind of thing, so (while you hear the line) "out of the night that covers me," you see the barber put the sheet over me so the hair clippings wouldn't fall on my clothes. And with the line in the poem "I have not winced not cried aloud," you see the barber stropping the old-fashioned straight edge razor. And then with the line "My head is bloody but unbowed," I was over the sink with the barber washing out the shampoo. Then with the closing line "I am the master of my fate, the captain of my soul," Happy Herman, the black guy, was sweeping up my hair clippings on the floor, a good closing shot to go with putting my glasses back on; all scenes of vanity.

But it lacked one thing, so I got Jack Brickhouse, who has gone to the great baseball bleachers in the sky, to give me a piece of his play-by-play for a baseball game, which the Cubs lost. And I put that behind the thing in the final film. It had one showing in a theater, the Esquire Theater in Chicago, and I was sitting there proudly watching people wonder what the hell was going on. It lasted about two and a half minutes, something like that, and this old guy in front of me said, "There's a radio on, there's a ball game on." He didn't understand that it was part of the track. I must say the poem itself just cried for a satire. The idea that we are masters of anything is belittled by fate and time.

There was a woman who was actually involved in the Oklahoma City bombing; she lost a child in the horror of it all. But, her position was that she had gotten over it. She thought McVeigh should not be put to death but given life in prison. Because she felt that it was like being bitten by a snake in the forest, and if you don't stop to take care of the wound itself, but chase after the snake to kill it, you just compound the evil.

There's nothing that's more transparently a lie than the line, "I feel your pain." Thank God we can't. What if you could take a pain and pleasure meter and say, "I wonder how much pain there is in the world at this moment? And I wonder how much pleasure?" Which is the greater of the two?

What would you think?

I would say pleasure. You know they talk about "It's terrible to hurt someone -- any human being," but then they forget that life is possessed by many other things too.

Are you familiar with the term "hypnogogic"? It's the state right between being awake and asleep.

I've been there many times.

For me, in responding to your work, there is a sense of "Oh, this guy could be almost asleep or he could be waking up right now." You know, the voice that you use often has that kind of hypnogogic quality to it.

Some of the writing I do, in what I call the space between awake and asleep, is a sort of device, not only to write, but to slip off. I've written hundreds of things. They're always the same form. They're eight lines long and they always begin, "Maybe the moment ... " And then I'll think of the next line and after I've got eight lines, two quatrains, I'll scribble it down on a piece of paper. And I nod off immediately. For example, here's one I did the other night:

Maybe the moment

has something to do

with what's going on

in Kalamazoo.

everyone's leaving

the town is in shock

where are they going?

To Manitowoc.

The reason I write about "the moment" is because that's one thing that boggles me. How many centers of the universe there are when you consider the number of people in each. Each of those centers has a point of view and each moment is different for each of us, so, in a way it's sort of a monstrous conceit that I could really add up all the moments there are. The truth will be untold because whatever you leave out conditions what you leave in. For example I wrote one the other day:

Maybe the moment

whatever it means

is under a pile

of old magazines

that I can reread

some day when I choose

to find myself lost

in used to be news.

Do you trance yourself out doing this stuff? I know it trances other people out.

Oh, no, I'm pretty aware. I use some silly truth as a diving board to get into something else. Many winters ago, when we had a coal furnace, I'd go down and shovel and put in some coal, bank the fire. I went down there one night and there was a rat down there. And I thought, "Oh, my God!" So, I bravely went upstairs and closed the door quickly, and worried about the house freezing. Finally I said, "Well, I have to go down and fix the fire." And the rat wasn't there. Well, now that isn't enough of a story. So, I picture myself down there trying to get the coal with the long shovel and I don't go near the rat. And I put it in and then I go up upstairs again and I call my friend with the hardware store and, even though it's Sunday, I get him to open up and I buy $10 worth of rat poison, which I bravely throw in from a distance to the rat, and it kills him.

And I discover that I have nearly $9.75 of leftover rat poison, which I don't want around the house. So, I get in the car and I drive to a neighborhood that I never go to normally and I just throw it out the window. And then I hear later that the dog who used to howl at the moon, a poet dog, died from the poison and all the neighbors in that neighborhood have a theory as to which lousy neighbor poisoned the dog. Of course, I'm quite a few neighborhoods away.

That's the extension. It starts with the rat.

Yeah, it starts with the rat and my fear. And now they do shows like that "Fear Factor." They get white mice and dye them gray and scare girls.

You take a kernel of something that has happened to you and use that as the seed?

No, it's what I would like to have happen. For example, the tattoo. I've never been tattooed or had my ears pierced. What I picture is having a tattoo, maybe an eagle, but it would be just sitting there on my forearm. And that's one thing that bothers me: that it wouldn't change. So the idea that a tattoo would just sit there and never change has me thinking, "Well, wait a minute, what if I had a special ink that would cause the tattoo to slowly move, very, very slowly along my forearm across my shoulder and to the nearest opening?" And it would disappear, maybe you'd see the eagle half on my cheek and half inside my mouth disappearing. And it would creep along and wander around and get stuck maybe under my kneecap and I'd rub it loose and it would be changed while it was inside of me and it would move on and come out, not looking like an eagle at all, through one of the other orifices. And so I'd think about getting a scientist to develop this super tattoo ink that can do this amazing thing. But give it to a tattoo artist and it might cause a problem. What if people don't want their tattoo changed?

I have a doctor friend who is in research in narcolepsy at the University of Chicago. He has about 40 dedicated drones working with him measuring sugar consumption as they move from axin to dendrite across synapses. What I always say to him is ... "Hey, when you find out where 'whimsy' is, or 'notion,' give me a ring." Well, by God, he came by a couple of months ago with two guys from Frankfurt who were selling the University of Chicago a device that you could use with a computer to do an XYZ of the brain for tumors. And he wanted me to see it. It was a beautiful program and I asked them, "Do you think you can find whimsy?" "Oh, yeah, we could do that." And I said, "Well, set it up." And then I'd say, "OK, I'm being whimsical now." But what if I was fooling myself and I wasn't really being whimsical, I just thought I was? When we define something are we really it? And can we find it?

I think satori is where you reach that state of enlightenment yet you don't realize you're in it.

Yeah, that's where the truth is right in front of you when your back is turned. There was a short film once, a fellow was scribbling a message and you think, "What's he writing?" You don't know what it is. He folds it up carefully and puts it in his pocket and he goes to the top of the Eiffel Tower. He takes this note out and you think "Uh oh, this is his last statement, he's gonna jump," but, no, he makes a little airplane out of it and he throws the note off the top of the Eiffel Tower and an accordion starts to play light-hearted French music. And you follow this little paper airplane flying willy-nilly wherever. And it goes down, swooping gracefully over the rooftops of Paris and it goes through a window and lands on a woman's lap. She opens the thing up and reads it, closes it. Walks out of her place and goes to the Eiffel Tower, goes up to the top and slaps the man in the face.

Did you ever want to be famous?

I love applause, and I love an audience, and I love to do what I do, but I become so caught up in what I'm doing that all the marketing and focus of getting there and staying there, schmoozing, making the right moves, becomes something else really. I guess I have that kind of Swedish melancholy that the Brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Andersen had, that -- after it's over it's over. No, I think being in the right place at the right time sometimes can ruin you. It's easy -- so much of what happens is luck. I've been doing albums now since 1956, and I've met wonderful people and I've got a lot of people that e-mail me now and it's very gratifying. But, the nice thing about where I am, hidden away here, is that I can do almost anything I want to do and I have nobody to blame but myself.

Shares