When Academy Award nominations are announced in February, a familiar crop is expected to contend for the best actress prize: Judi Dench, Nicole Kidman, Sissy Spacek. Oscars rarely go to actors in foreign-language films (Roberto Benigni notwithstanding), but let's not forget Charlotte Rampling. Recently Entertainment Weekly made its case for her as a dark-horse Oscar candidate for the French film "Under the Sand," and deservedly so: Rampling's performance as a grieving widow who descends into madness is the culmination of a brilliant career spent mining the darker realms of the human psyche.

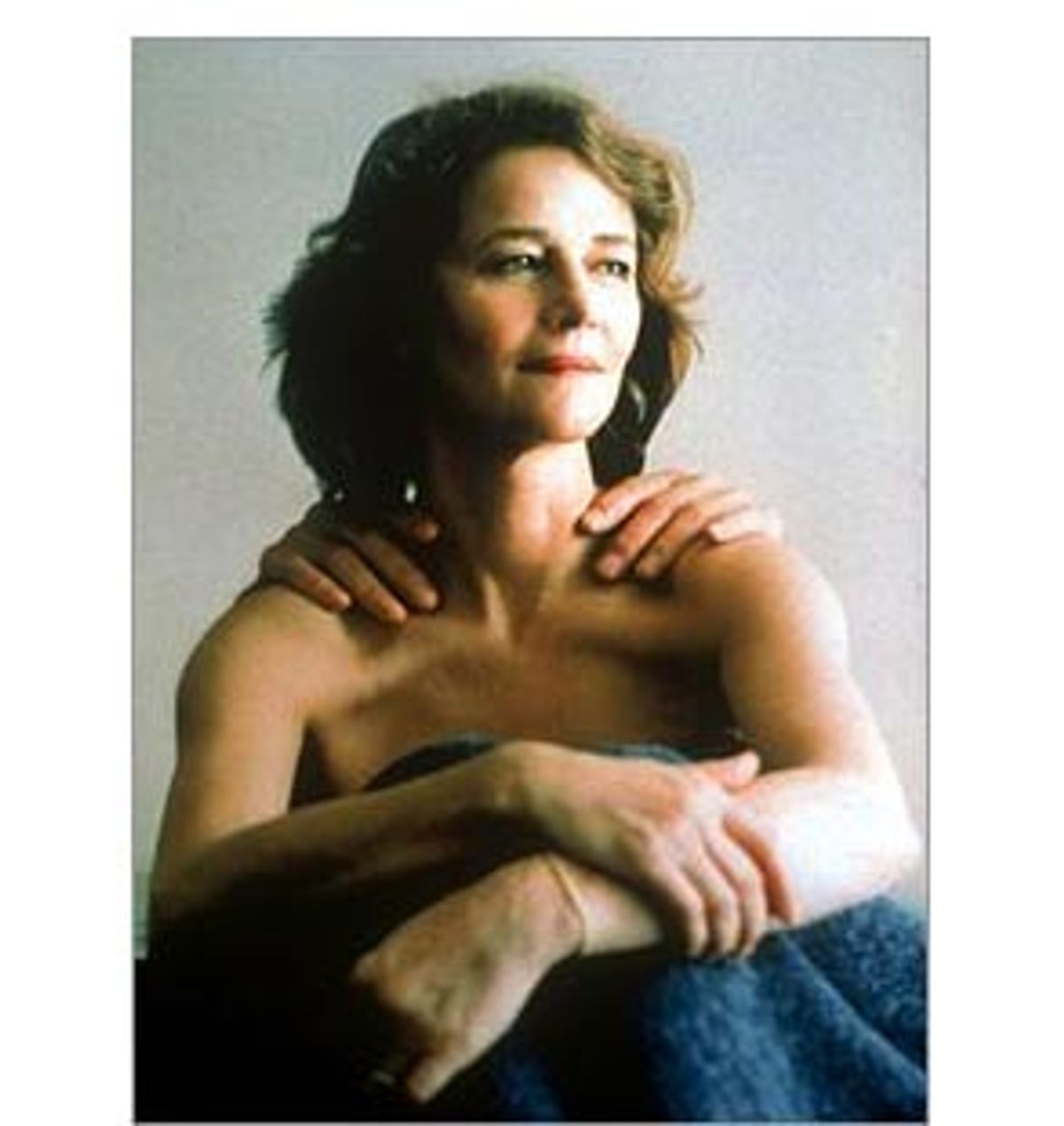

More beautiful than ever at 56, Rampling is also an exception to the standard fate of middle-aged actresses, who often go from headlining roles to the bottom of Hollywood's food chain before you can say "sexual double standard." For every Marlene Dietrich or Susan Sarandon who beats those odds, there are countless Norma Desmond types who fade away.

So why has Rampling endured? Her characters are bewitching and elusive, capable of great affection but always on their own terms. And no matter how icy they get, somehow they always leave you wanting more. "I always wanted to be your trampoline," the British rock band Kinky Machine sings in their song "Charlotte Rampling."

Legendary English actor Dirk Bogarde, Rampling's costar in Luchino Visconti's epic "The Damned" and Liliana Cavani's cult classic "The Night Porter," called it simply the Look. "I have seen the Look under many different circumstances," Bogarde once wrote; "the glowing emerald eyes turn to steel within a second, [and] fade gently to the softest, tenderest, most doe-eyed bracken-brown."

The daughter of a British colonel and a painter, Rampling married electronic music pioneer Jean-Michel Jarre in 1978 (they recently divorced) and has remained in Paris ever since. Largely eschewing Hollywood, she has instead chosen an eclectic variety of European and independent films (as well as some darker studio pictures) that push the borders of conventional morality. In "Georgy Girl," one of her first roles, Rampling's character gives up her baby to keep swinging in '60s London. Despite her love for Paul Newman in "The Verdict," Rampling betrays the desperate little-guy lawyer to his Goliath opponents. The enduring image from "The Night Porter" is Rampling dressed in Nazi-style S/M. And then there's Nagisa Oshima's "Max, Mon Amour," in which her character cheats on her husband with a chimpanzee. Yet the string of humiliated men in Rampling's wake always come back: They want to be her trampoline.

As someone who's bucked Hollywood for a life and career in Europe, do you care about the Oscar buzz you've received for "Under the Sand"?

I've never aspired to winning an Oscar, but it's exciting when people start thinking about it for you. I don't think I'll actually be nominated, but the recognition I've already got is just as good.

Your career has largely been devoted to darker characters. Has that happened naturally, or has it been by design?

When I first started to choose rather strange films, people would wonder why I would go toward these rather risky, daring, sad, decadent pieces, which weren't necessarily indicative of how people saw me in my everyday life. People still say to me, "You seem so different in movies," and I say "No, it's my shadow side." This is where the undiscovered parts of ourselves emerge.

Of all the legendary actors you've worked with -- Robert Mitchum, Paul Newman, Robert De Niro -- Mitchum seems the one you personally resemble the most: talented and professional, but at the end of the day part of you just doesn't give a damn. How did you two get along?

I really only understood the extent of how we were similar many years later. He had a mysterious appeal to me. Mitchum doesn't show his real self very easily, unless you're somebody who he thinks will enjoy it. That started to happen with me at the end of the shoot, which is common. You often start to get a feel for the people you're working with as it's time to leave. But I think there's something about that generation: Those guys like Newman and Mitchum had more of a hold on bringing out something on-screen from inside. Their interior world was much less exposed. Now everything's talked about, everything's out there, which I think is a pity.

Then how did you fare on "Stardust Memories" with Woody Allen, whose persona is just the opposite?

I don't think Woody Allen and I are similar in any way, but that there's something in him that brought out the fun side of me, which I hadn't seen in a long time. It's not necessarily related to the role I played, but he has a very comedic, ironic look on life and how people are, and I loved to see how he recognized the clown in me.

People say Allen likes to improvise on set. Was that the case with you?

Yes and no. Woody would rather improvise himself and let the actors bounce off him in a way that he can sort of pre-understand. You don't really have that much more freedom [with Allen], but you don't need it. Cinema is not like the theater: We have very little time together. We may have a lot of downtime on the set, but the actual filming of movies is short and quick.

Two of your most talked-about roles, "The Night Porter" and "Max, Mon Amour," deal with sexual taboos. Do you enjoy pushing boundaries?

Provocative subjects provoke me, and I need that. Otherwise, I'll get bored. I've always searched out that type of work, and it's not just coincidence that I chose these particular films. They are related to me, because I see myself in them.

People have responded to "Under the Sand" in part because on-screen portrayal of sexuality in older women is so rare. Why do you think that is?

The cinema is more interested in youth, and I can understand it. Young people are more attractive and beautiful. But what a woman of my age has to offer is extraordinary [laughing], and you'll only know it if you allow them to come into your life.

Do you see a double standard in movies between women and men of this age?

Yeah, I do. But honestly I do think older men are sexy, and for women that's not always quite so. There's a natural cycle that, when you're in your 50s, it's not all about that anymore. You don't necessarily have to seduce people anymore, whereas men still like doing that. I like it here in Europe, where the older woman is the venerated one: not necessarily looked up to as a sex symbol, but she's a wise woman, someone who is very beautiful but not just there to be jumped on.

Are you more of a method actor, where you have to submerge yourself in the character's identity, or can you just show up and deliver your lines?

I think about the role a lot before I play it, but when I actually come onto the set, I don't want to have to think about it at all. It's all in there somewhere, and I just call it up. All actors have a great palette available to them, and I don't think you ever need to be afraid that you're not going to call the right emotions up.

So how did you find working with a classic method actor like Paul Newman?

With Newman, I just felt a great mystery around this man. He was shy, he was timid. But you could also feel he was someone who'd had many knocks in his life and had got through them and found ways to come to terms with them, whether it was his race-car driving or whatever. Things seemed to make sense to him, which made him calm as an actor, and therefore great to work with.

We've talked about the similarities between the characters you've played. Is there a connection with some of the great directors you've worked with, like Luchino Visconti, Sidney Lumet and John Boorman?

The connection is that I trust them, and that allows me to lose control, to let myself be taken away. If I'm prepared to let go, I can disappear into the director's world, and become a manifestation of their fantasy. I like that seduction that goes on. And I'm completely unresisting, which I've noticed is quite rare. A lot of actors resist terribly, that's just how they work.

Which is ironic, because it's the opposite of your on-screen persona.

Yes, I probably look as if I'm going to resist like mad whatever the director wants, because I look quite fierce a lot of the time. But I don't want to resist. That sense of daring is what allows me to give of myself.

How are you different from your characters?

I have a playful, childlike side that only my close friends and family sees. I think to stay closest to your source of creativity is to stay closest to where you were when you were very young. You didn't worry about the pressures of society so much. You just were. I think that part of me has always been very protected.

What are your memories of that young age?

I remember imagining everything: playing all kinds of games in my mind and all the time saying, "Let's pretend. I'm this, you're that, and here we go." My sister and I used to make these toy horses and pretend that we were these supreme riders, and we'd ride all over to places where we could never really go. It was extraordinary. And I still have some of those horses we made.

Before this interview, I found a Charlotte Rampling chat room, where people talk endlessly about you and your career. Considering your stated desire for privacy and reticence about fame, do you find that sort of fandom flattering or unsettling?

That's what has always happened, with fan clubs and that sort of thing. I think it's fine. If they want to get together and talk about my screen persona, they're imagining this whole other character that's probably much more interesting than plain old me.

So you're somewhat sympathetic?

Yes. For example, I've never worked with Robert Redford but I did this brief cameo appearance in "Spy Game," and I did it because I wanted to have the chance to meet him, and to give him a kiss [laughing], which the script called for. He was a really great guy. So I can understand.

Are there any types of roles you haven't played that you'd like to?

Not really. I'm not really very inventive in that way. Instead I like to feel that somebody else has really thought about me and come to me. It goes back to that notion of letting myself go without a net. You can't plan out that sort of thing.

It's sort of a romantic way of running your career.

Yes, but otherwise I'm merely another member of the rat race. It's like Marie in "Under the Sand": Her sensuality is something that she subconsciously needs to keep alive. I feel the same way about acting. I have to let it breathe by not forcing it. And it's funny: Today doing what you want is a romantic notion, but 25 years ago it wasn't. That's just what we did. It sounds clichéd to talk about the importance of holding on to your beliefs and intensity. But the clichés are true. I've never sold out, ever.

Do you think a lot of actors sell out?

I see people sell out all the time. They do it once and they try to turn it around, but then it happens twice, three times. How many times do they have to beat themselves over the head before they understand? I may have made some odd films, but I've never made crap, and I've never done it for the money. It's about honor. Honor is a warm thing, a caressing thing. I'd rather go to bed with honor than a bank balance. I'll feel much better in the morning.

Shares