The '60s loomed and Fabian-soaked America needed a musical fix. Elvis, only two years into his career, had been drafted and shipped off to Germany, where he recorded not one note. And the void only deepened when three of the country's most promising young talents, Richie Valens, J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper) and Buddy Holly, died in a plane crash one wintry night in February 1959. On the jazz front, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker experimented with Caribbean and South American rhythms, and Miles Davis' revolutionary album "Kind of Blue" set the precedent for a decade of modal riffs and was considered quite groovy. Neither, though, caused any mass hysteria. Of course, there was Sinatra, who by then was more popular than ever, but he just ring-a-ding-dinged like always.

Then, out of nowhere, out of Africa, came Babatunde Olatunji, drummer, singer, sage. He of the primal chants and flowing robes and tribal beats, a strange stranger in a strange land. No one, not even his African-American brothers and sisters, really knew what to make of him at first. But if ever the country was primed for something new, something wild, it was now, and soon he turned gapes and murmurs into smiles and cheers, and hi-fi's everywhere pulsed with the strains of the aptly titled "Drums of Passion," Olatunji's breakthrough release on Columbia Records. Four decades later, the album has sold tens of millions of copies worldwide and has inspired beyond measure, musically and otherwise.

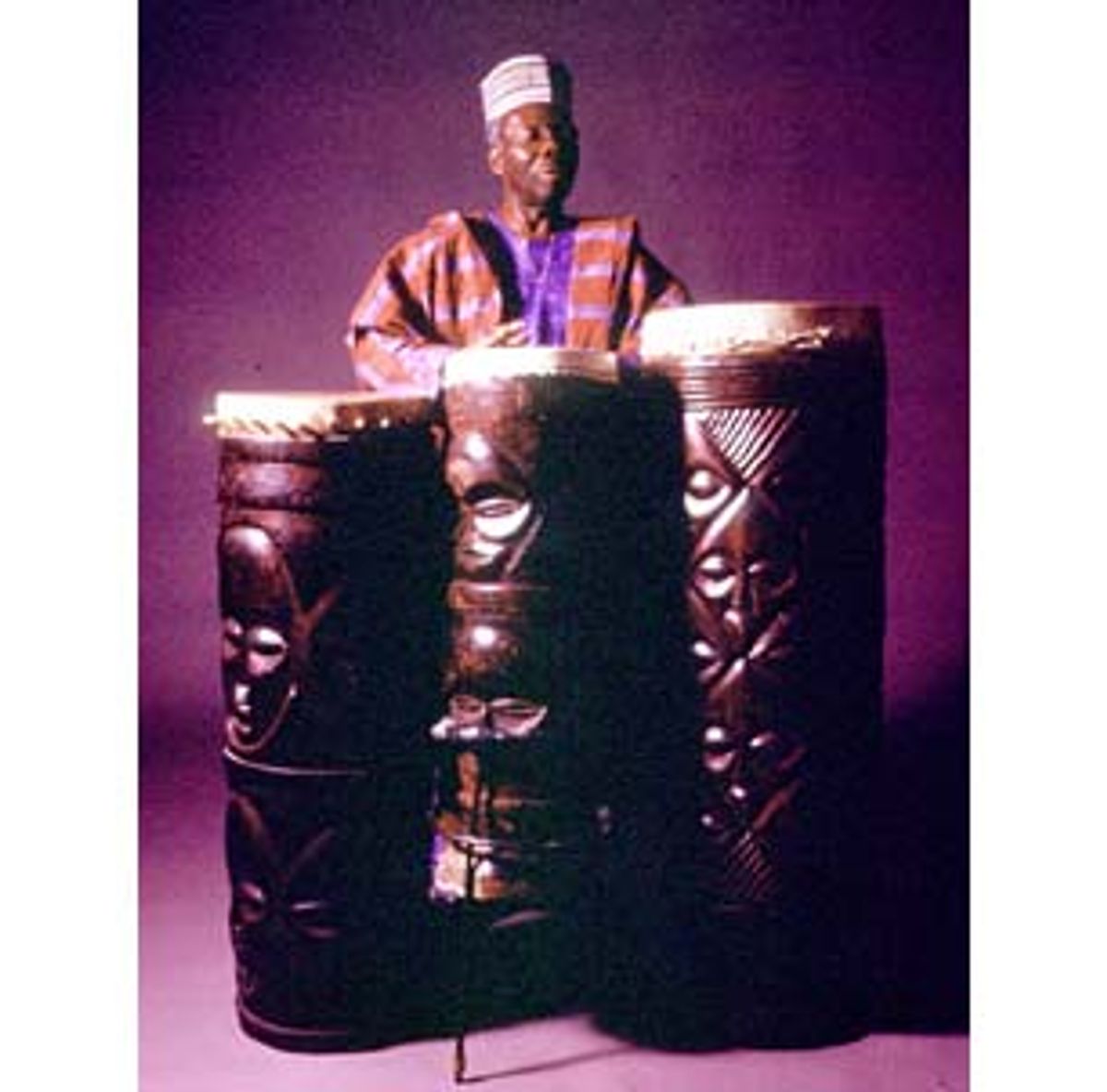

But then, it's always been Olatunji's nature to inspire, to teach, to enlighten. In fact, he has long looked the part of the proverbial sage on a mountaintop, the serene soul perched at the precipice, ready to illumine world-weary travelers. His visage, strikingly beatific, is the sort of preternatural mug that quells evil spirits and tames wild beasts. His voice, still thick with the timbre of his native Nigeria, is both soothing and fervid, equally suited for bedtime stories and suicide prevention. And his graceful comportment radiates an aura of supreme confidence, which no doubt helps stoke the illusion that he is vertically endowed, a veritable giant among men, when in fact he is only 5-foot-7. But these extraordinary attributes are mere complements to his most dazzling quality, that which has rendered Olatunji a near diety in the eyes of millions: his undisputed mastery of conga drums.

"Rhythm," he often says, "is the soul of life!" It is a credo to which he has subscribed since he was raised on rhythm in Ajido, a Nigerian village peopled by the millions-strong Yoruba tribe. There, he was schooled early in what he has termed the "evocative power" of drums, specifically, conga drums hand-fashioned from wood and goat hide. They gave voice to happenings profound and mundane, to births and deaths and everything in between. They were, in effect, the chief chroniclers of village life and thus were carefully hand-crafted so as to resonate with maximum effectiveness. Even today, Olatunji's instruments retain a certain proletarian quality owing much to workmanship that has changed little in centuries.

"There's a trinity about drums," he has noted. "There's got to be a spirit in the body of the drum. And the wood has to stay alive in order for it to produce sound. The skin on the drum is alive, too. But you've got to know how to tan it, because when it [encounters] the spirit of the person playing it, it then becomes an irresistible force."

In 1950, Olatunji applied for and received a Rotary scholarship to attend Moorehouse College in Atlanta. Bent on bettering the lives of his Nigerian compatriots, he strove to become a diplomat, spending his undergraduate years studying political science, sociology and psychology, disciplines in which he might find ways to quell the civil unrest that threatened the world, especially his motherland, Nigeria, and his adoptive land, America. It wasn't until he formed a small drum and dance ensemble during his postgraduate days at New York University, where he continued his diplomatic track with the study of public policy, that he rediscovered the captivating, transcendent effect of his native music on American audiences. Olatunji soon ceased his academic endeavors and dedicated himself to the drums.

It was 1958, and the boy who had dreamed of one day becoming an ambassador was now a man on the way to attaining his goal. Not officially, and certainly not in the traditional sense, but what did it matter? Music and rhythm spoke louder than words, anyway. And the time was ripe for social revolution: His sudden rise to fame came during an era that witnessed America's most epic (and tragic) struggle for civil equality.

In this same period, the year before he and his congas would pierce universal consciousness, he began his musical ministry in earnest. He even toured portions of the United States with Martin Luther King Jr., drumming at civil rights rallies and other such assemblies. He would do likewise later with Malcolm X. Consequently, Olatunji's name soon became linked as much with social issues as with music, though his ardent activism never overtook his affinity for the stage.

Among the countless performances he gave was a high-profile gig with the Radio City Symphony at New York's Radio City Music Hall, where there happened to be a Columbia Records executive in attendance. Impressed by Olatunji's raw, exotic riffs, he immediately signed his new find and introduced him to one of Columbia's top music producers, John Hammond. An A&R wiz who would go on to bring Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen into the Columbia fold, Hammond helped sculpt Olatunji's unique sound while maintaining its searing integrity. The resulting "Olatunji! Drums of Passion" set ears and souls afire.

Before the album was released, or even titled, however, Olatunji, a spirited proponent of musical education programs, told the Columbia suits of his notion to tour elementary schools, first in New York City and neighboring states, then nationally, to promote the album and showcase this revolutionary sound of his. Of course, it wasn't revolutionary to him, but to most everyone else it was cutting edge. Record company flacks also seemed to think it was a bit risqui, especially for children. Think of the children! "[Columbia] said, 'What are you going to take that to schools for? What are we going to call it? '" Olatunji recalled. "And I said, 'Drums of Passion!' They hesitated. Now, when you think of the language on television today, the fact that they hesitated is amazing!"

Consequently, the tour received no promotional support from the label. But Olatunji maintained his course and, in the spring of 1959, having secured sponsorship from the Organization for Childhood Education and the Rockefeller Foundation, he struck an agreement with the New York Board of Education whereby he would perform at weekly school assemblies in Queens, Long Island, Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx. He did likewise at schools in New Jersey and Connecticut, then convinced other school systems around the country to follow New York's example, and began a nationwide sweep. At a few hundred dollars per gig, the tour would by no means make him wealthy, but it would allow him to showcase his music before throngs of malleable young minds, the next wave of voters and politicos and power brokers.

Two youths in particular who witnessed Olatunji's awesome exhibition and, consequently, became lifelong disciples, were the late comic Andy Kaufman and Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, both of whom were elementary students on Long Island, where Yoruba tribesmen aren't exactly commonplace. Thus, Olatunji, with his otherworldly garb and rough-hewn instruments of beast hide and teak (this was the anti-Fabian if ever there was one) had their rapt attention even before skin met skin.

Kaufman, for one, was so impressed that he soon purchased his own congas and sought out lessons from the master himself at one of Olatunji's many outposts in Greenwich Village. Years later, he even went so far as to incorporate his own alien breed of conga drumming into many of his performances. Hart, similarly floored by Olatunji's impassioned exhibit, followed a more predictable and infinitely more renowned percussive path, eventually joining forces with psychedelic kingpin Jerry Garcia to form the Grateful Dead.

During his promotional tour for "Drums of Passion," and on tours for his subsequent Columbia albums in the early- to mid-1960s, Olatunji, whose fame was rising steadily, continued to champion education and social reform. His chant "Akiwowo," from "Drums of Passion," got frequent airplay on mainstream New York radio courtesy of WLWU DJ Murray the K, and on the television front, Olatunji made appearances on Ed Sullivan's variety program in 1961, and Johnny Carson's then New York-based "The Tonight Show" in 1963.

In late August 1963, upon completing an extended engagement at the Troubadour in Los Angeles, he sped (literally -- he got a ticket along the way) cross-country to attend the March on Washington in the nation's capital, the storied gathering at which King delivered his prescient "I have a dream" speech, which echoed Olatunji's beliefs and hopes. Inspired, he began to more fully realize how his growing celebrity could be an effective vehicle for his own cultural and political agendas.

The next year, following performances at the 1964 New York World's Fair, where he was hired as a featured performer on the African Pavilion, one of 36 such pavilions that spotlighted foreign artists, Olatunji used most of his modest paycheck to establish the Olatunji Center for African Culture at 43 E. 125th St. in Harlem. For the next quarter century, until it closed in 1988, he and his volunteer staff hosted workshops and offered music and dance lessons (only $2 apiece), all intended to promote African culture.

By 1966, Olatunji's contract with Columbia ended following his sixth album for the label, "More Drums of Passion," intended as a sequel to his triumphant debut effort. But it, as well as the four albums he'd recorded during the years in between ("Afro Percussion," "Zungo!" "Flaming Drums!" and "Highlife," the last being the most jazz-infused of the lot), failed to achieve the widespread popular and critical acclaim of their predecessor. And so, for the next two decades, Olatunji found himself spending much more time on the road than in the studio, tooling cross-country in a station wagon to various performances, largely at universities, where he happily, passionately preached his philosophy of peace, love and knowledge through rhythm.

He occasionally returned to the studio to make guest appearances on records of such celebrated jazzmen as Cannonball Adderly and Pee Wee Ellis. And while he never had a chance to do so with John Coltrane, he remained a prime influence on the lauded saxophonist who, impressed not only by Olatunji's percussive prowess, but by his efforts to revive African culture in America, even lent monthly financial support to the Olatunji Center in Harlem until his untimely death in 1967.

Cut to: Oakland, Calif., New Year's Eve, 1985: After toiling in relative obscurity for nearly 20 years, this was a second chance of which Olatunji had not even dreamed. His former pupil Mickey Hart, now a world-famous rock 'n' roll drummer, had reintroduced himself to his mentor at one of Olatunji's shows in San Francisco and invited Olatunji to open for the Grateful Dead at a New Year's bash at the Oakland Coliseum. Hart, from day one a fervent champion of Olatunji's, figured it was about time student and teacher combined forces to blow some minds, not to mention roofs.

And his instincts were right. It was a stunning night, one that saw Olatunji in top form, flailing and tapping and thumping and chanting, ushering in the new year the only way he knew how: with a bang (actually, many bangs), not a whimper. The tie-dye ocean swirled. The capacity crowd crowed, grooved to the beat, even sang along. In short, they dug it, and dug it big. Baba, as he'd become fondly known, rocked the house. Baba was back.

Proclaimed Olatunji, "When I think of that night, it gladdens my heart." Hart, too, saw the crowd's zeal and realized what potential there was in collaborating with his boyhood hero. Beginning in 1986, Olatunji and Hart created "Drums of Passion: The Invocation," a collection of Yoruba tribal devotions to various gods, with Hart producing and occasionally accompanying on hoop drum and concussion stick. The album, which also featured the guitar licks of longtime Olatunji fan Carlos Santana, hit the shelves in 1988. Hart also reintroduced Olatunji's 1986 album of love songs, "Dance to the Beat of My Drum," which was renamed "Drums of Passion: The Beat," and re-released as part of Hart's international series "The World" in 1989.

But it wasn't until 1991, when Olatunji and Hart formed the group Planet Drum, that their efforts received large-scale attention and praise. The ensemble's first album, "Planet Drum," earned a Grammy award and exposed Olatunji to yet another generation of listeners. Six years later, their 1997 effort "Love Drum Talk" garnered Grammy attention as well, though this time only a nomination. Nevertheless, it got some critical raves. The Jazz Times review called the album "a powerfully infectious meditation on the nature of indiscriminate love that grooves as it teaches ... [Olatunji] delivers the cure once again."

Olatunji, now 72, still resides in New York, his epicenter for more than four decades. While he is somewhat grayer and slower-moving than when he began, his social activism is stronger than ever (not long ago he attended his first star-studded Hollywood charity function at the home of Goldie Hawn), He continues to teach and perform around the city, the country and the world; it is a calling taken seriously, heeded joyously. Plainly put, Baba loves his work.

"The spirit of the drum is something that you feel but cannot put your hands on," he once mused, attempting to explain the allure of his craft. "It does something to you from the inside out . . . it hits people in so many different ways. But the feeling is one that is satisfying and joyful. It is a feeling that makes you say to yourself, 'I'm glad to be alive today! I'm glad to be part of this world!'"

Shares