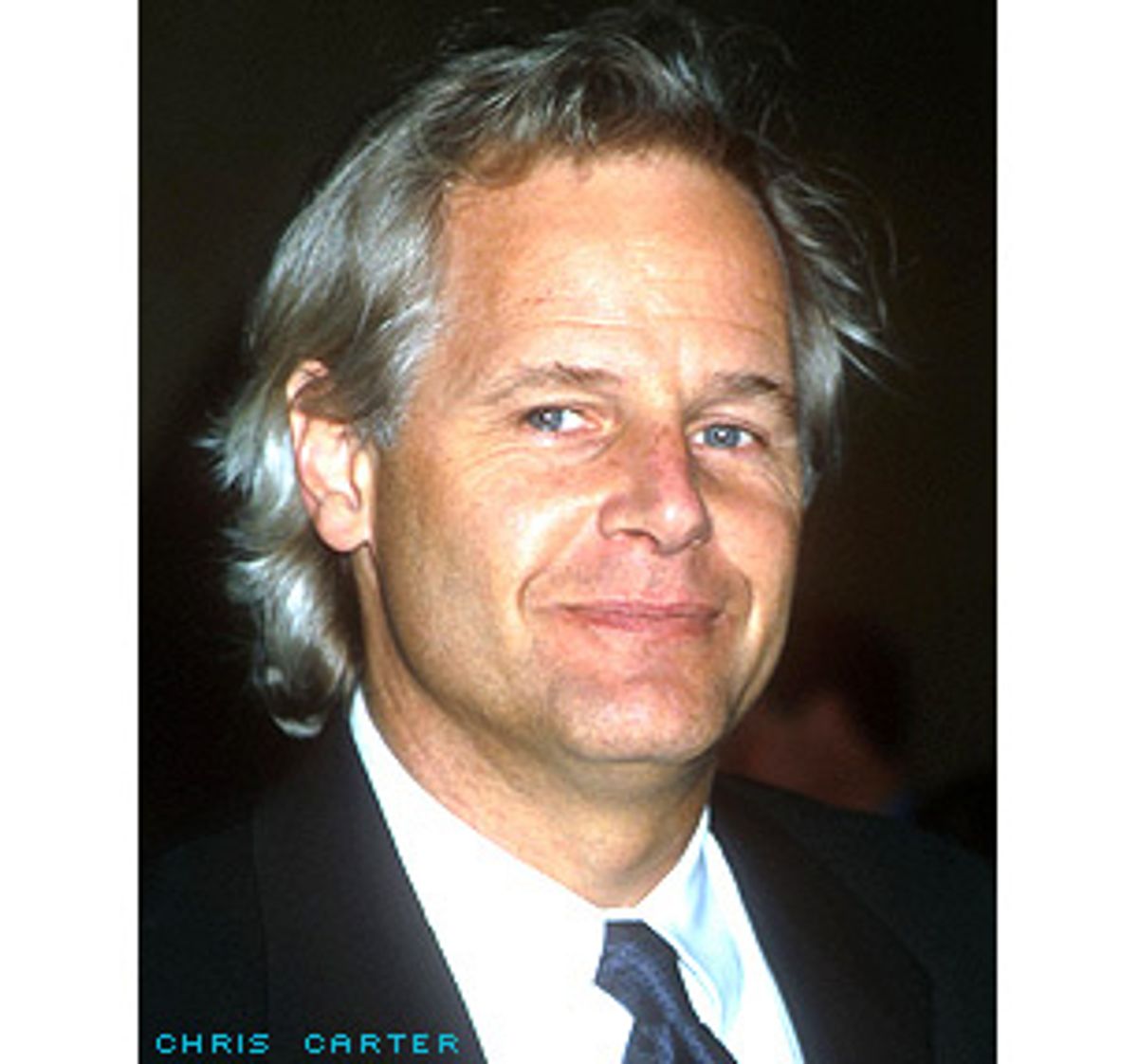

Chris Carter, the world leader of the sci-fi geeks, is also the definitive anti-geek. You

might expect the brain behind "The X-Files" to look like one of those guys you see at

the "Star Trek" conventions sporting a mullet haircut and glasses held together with

duct tape, but Carter doesn't even wear glasses. He's tall, tanned and handsome,

well-scrubbed and well put together.

He made a rare public appearance recently in Santa Barbara, Calif., which is where he

lives part-time. It's also the place he most likes to surf. That's what they say about

him in the online chat rooms, anyway. They also say his nickname is "Carver" from his

days as a writer for Surfing, and that he surfs goofy-foot, which means he keeps his

right foot forward. He chose the character name Mulder because it's his mom's maiden

name and named Scully after famed baseball announcer Vin Scully. But if you're an

"X-Files" fan worth your salt, you already knew that. There's little they don't know about

him, those fans. In the chat rooms, Carter is commonly referred to as "God."

After Carter was introduced to a packed auditorium of 800 at Santa

Barbara's gorgeous seaside University of California campus, the

audience erupted into sustained, possessive applause. Carter strode

onstage in tan pants and a blue, button-down oxford

shirt. God was in the house, and he was wearing Banana Republic.

Before Carter arrived, the middle-aged woman in front of me had been wringing her

hands in anticipation. When he was 10 minutes late, I feared a nervous breakdown.

Now that he was here, she breathed easier but looked like she might cry.

Carter carried himself as though he were meeting up with some dudes for a beer.

Despite being the '90s' most intense purveyor of paranoia, his entire demeanor in

person seemed to say, "What, me worry?" After the applause died down, he initiated a

penchant for deflective self-deprecation that would last all night -- "I have a lot of

family and friends who are probably wondering why you are clapping."

Carter was introduced by Constance Penley, a professor and chairwoman of the University of California at Santa Barbara Film Studies

Department, who has herself written extensively on science fiction. "The creation of

'The X-Files' was arguably the most important event of the decade, except for possibly

the discovery of the Mars rock, or the impeachment of the president," Penley said. "Of

course, in the 'X-Files' universe, the two would be connected."

Penley continued to gush: "The show was so sophisticated in its presentation of the

ethical and social dimensions of science that you would have thought that Chris Carter

had been trained as a philosopher, rather than a journalist."

A philosopher? A blue-collar guy from Bellflower, Calif., a crummy Los Angeles suburb?

His dad was a construction worker; his mom, a housewife. He earned a journalism

degree from cheap California State University in Long Beach in 1979, paying his way through

school as a potter. For a while, he did construction. He started working as a reporter for

Surfing magazine but, after seeing "Raiders of the Lost Ark" six times in six days,

began to entertain the idea of becoming a scriptwriter. He was encouraged by his

screenwriter girlfriend, Dori Pierson.

That's when things began to get weird.

In 1985, Jeffrey Katzenberg, while still head of Disney, saw a script Carter had written

and gave him a development gig for $40,000 a year -- chump change in Hollywood,

but twice as much as Carter had ever made in his life. He worked on such forgettable

product as "Meet the Munceys" and "B.R.A.T. Patrol." But his work impressed an

up-and-coming suit named Peter Roth, and when Roth became president of 20th

Century Fox in 1992, he stole Carter away to develop new shows. Carter's "X-Files"

pitch didn't fly at first. Too out there. But Carter did some research, showing in part

that 3 percent of all Americans believed they had been abducted by aliens, and Fox

took a chance.

Carter's story, obviously, is too whacked to have been scripted on any show besides,

perhaps, his own. "It only proves he's an alien," Penley said. "He has been placed

here by creatures who did not know how to construct a believable narrative about how

one becomes a television producer and creator of a mass cultural phenomenon."

Carter's appearance in Santa Barbara came just a day after he began work on the final

episode of the show's seventh season, which he revealed will be called "Requiem." It

could be the last "X-Files" show. Carter and Duchovny's contracts come up this season.

And even though Gillian Anderson is still under contract, she's said to be unsure about

returning. Meanwhile, Duchovny has filed a lawsuit against Fox protesting what he sees

as sweetheart rerun licensing deals.

"Elian Gonzalez' future is more certain," Carter remarked.

But even after 160 episodes, Carter said, he still has more stories to tell, and would

like to keep going: this, despite the incredible weirdness that the job has brought into

his life. As he told the crowd in Santa Barbara, the weirdness began before the series

even made it on the air.

From the start, Carter envisioned the dichotomy of an inquisitive, credulous male lead

working with a female lead who combined elements of rationalism and skepticism with

a deep spiritual yearning. The studio accepted Duchovny immediately for the role of

Fox Mulder, but didn't warm to Gillian Anderson as Dana Scully.

"Gillian was unknown and when she came in she was disheveled," Carter said. "She

wasn't a very good salesperson for herself. But she had an intensity and an

intelligence -- and she cleaned up well. I couldn't get the executives to see what I saw,

no matter how much I tried, and it really came down to the idea of how she would look

in a bathing suit. And I kept saying to them, she's not going to be in a bathing suit.

She wasn't the bombshell they envisioned. They thought it was going to be a show

much more like 'Hunter.'"

The only thing more difficult than dealing with the suits was dealing with the FBI. "Early

on, I was calling the FBI for some research. And they were very kind. They talked to

me about procedure and protocol, and then one day they just cut us off. They wouldn't

accept our calls and then about two weeks before the first show aired, a call came in

from the FBI and they said, 'Who are you and what are you doing?' And I swear to

God, it was like J. Edgar Hoover reaching up from the grave. I was that nervous about

it, as you can imagine."

The FBI's tune changed, though, when the show became a hit that glorified its work.

"All of a sudden we started getting calls from agents, individual agents, saying that

they loved the show," Carter said. "And by the end of the first year they took us on

what they call the 'Jodie Foster tour' of the FBI. They rolled out the red carpet as they

had done for her in 'The Silence of the Lambs.'"

Of course, the show hit just about the same time as the Internet started to take off, which added a whole new

dimension to fandom, and to Carter's job as producer of the first television show to

ever attract such a huge online following. "The Internet and 'The X-Files' grew up

together and it was great," Carter said. "The show originally aired at 9 o'clock on Friday

night and at 10 o'clock, I could get on the Internet and see what people thought of it.

It was great in the beginning."

But even that got weird. "It became overwhelming; it was too much," Carter said. "I

used to see every single piece of Internet mail. And now I see the reams of stuff after

every episode and I ask them not to put it on my desk. It's not because I don't care

anymore -- it's because I think there are lots of voices out there trying to be heard,

and a lot of it ends up being shouting. A lot of people do it just to get attention."

The intense fan passion for the show meant his personal appearances could also take

on an element of otherworldliness. "The autograph sessions at events like this are

always really odd," Carter said. "People try to slide you things, tapes of their

abduction. My wife and I have gone to bed at night listening to tapes of people's

abductions. It's better than counting sheep."

The obsessive-fan phenomenon played itself out in living color in Santa Barbara. The

event opened with Carter showing clips from the series. Then questions came from

Penley and another film studies professor, Lisa Parks. Then the night was turned over

to audience questions.

That's when things began to get weird.

Carter was asked if he had ever been dropped on his head as a child. He was asked

about his surfing. He was asked about specific episode elements too arcane for

anyone but the most hardcore fan to understand. He answered every question, no

matter how bizarre, with the same low key sense of humor, as if he knew better than

anyone how absurd it all was.

Had he ever been abducted?

"I have never had an experience with an alien, and I think they owe me a visit

because I've been their best P.R. man ever."

"What are you horrified by?"

"I would say an IRS audit."

"What about Mulder's fascination with pornography?"

"He's a lonely man."

"Explain the apparent homoeroticism between Mulder and Skinner."

"We're saving that for the cable series. The 'Triple X-Files.'"

In the end, Carter left the impression that he doesn't take the fandom and his own

place in it especially seriously, but that he does take his role as a popular storyteller

with the deepest sense of personal gravity and responsibility. "The X-Files" gets raves

in part because it addresses so many of the central themes of life in the United States

at the turn of the millennium -- a wariness about technology, a wondering about the

deeper questions of life and a distrust of big government.

It is his ability to bring these issues forth in story form that makes Carter want to

continue, despite the weirdness, and makes him so valuable to a culture that needs an

intelligent mirror of itself. And he revealed in Santa Barbara that what all the wondering

and yearning really come down to is not paranoia, but society's increased need for a

spiritual touchstone.

In his last statement of the night he talked about Scully's personality traits. "The most

difficult thing to reconcile is science and religion," he said. "And so we created a

dilemma for her character that plays right into Mulder's hands. So that cross she wears,

which was there from the pilot episode, is all-important for a character who is torn

between her rational character and her spiritual side. That is, I think, a very smart

thing to do. The show is basically a religious show. It's about the search for God. You

know, 'The truth is out there.' That's what it's about."

Then he sat down to sign autographs, and listen to people's abduction stories.

That's when things began to get weird.

Shares