To an outsider, Regent, N.D., seems a place one would visit only under extreme circumstances, perhaps to bury a relative or repossess a vehicle. Drivers approaching the town from Interstate 94 encounter few fellow motorists, only a vast expanse of brown prairie grass, rusted farming equipment and abandoned houses. The sudden appearance of a 40-foot grasshopper is as menacing as it is delightful -- Tim Burton meets John Mellencamp. The grasshopper is surrounded by 20-foot-tall blades of metal wheat that sway in the fierce prairie winds.

Gary Greff is transforming his hometown of Regent into the "metal art capital of the world." His vehicle for the journey is the inchoate "Enchanted Highway": a series of four (out of a planned 10) colossal metal sculptures on the two-lane county road connecting Regent to the interstate 30 miles north. Greff's aim is for the Enchanted Highway to eclipse the "western" town of Medora, complete with its "pitchfork fondues" -- every summer evening, folks gather on a bluff and fork slabs of steak into kettles of boiling cooking oil -- as the premier tourist attraction in the state.

If you want to make Greff cringe, call him an artist. Though he receives grants from both the National Endowment for the Arts and the state arts council, Greff considers himself an entrepreneur. So long as the temperature stays above zero, he can be found on the side of a prairie road, welding abandoned oil wells into sculpture -- what his funders classify as "folk art." Though his lifestyle is as austere as any bohemian's, Greff hardly fits the starving artist stereotype.

At 51, this retired school teacher lives in a trailer, does seeding work for a farmer each spring and makes it through the winter with the help of state fuel assistance, groceries brought to him by his parents and the bones his brothers throw him, quite literally, in the form of meat from their nearby ranch. "My ends don't meet very often," Greff laughs.

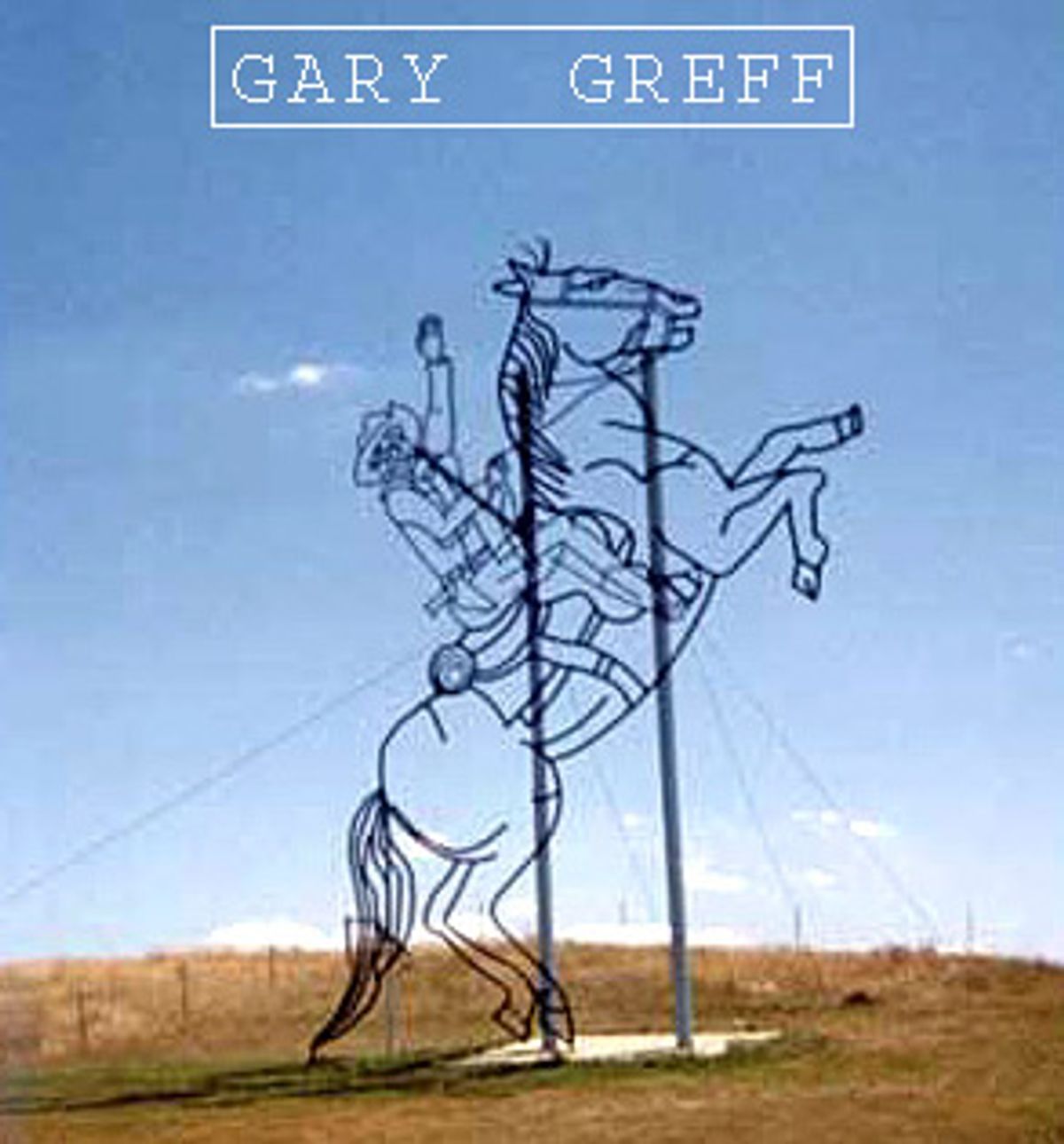

In addition to the grasshopper, Greff's Enchanted Highway offers a flock of four-story pheasants in various pecking poses, a family of tin people (soon to talk) and everyone's favorite rough-riding imperialist (and former state resident), Teddy Roosevelt, on horseback. Each sculpture site includes a small parking lot and a picnic table. Greff wants to make the highway family friendly and is paving the way for what he hopes will be a metal-art theme park complete with rides and a metal golf course.

Decorated at three-mile intervals, the highway capitalizes on one of North Dakota's greatest resources: space. The view from any of the four sculptures is not of strip malls or convenience stores; the view is not much of anything. Such spaciousness abets the illusion, however brief, that maybe towering pheasants do frolic in Regent, their very own home on the range.

Greff was a visionary even before he created the sculptures. The manufacture of "tearless" onions was his first entrepreneurial venture. According to Greff, the pre-sliced onions could be jarred and stored for up to three months, similar to pre-minced garlic. The product was tested and approved in Canada, received attention from CNN and "Good Morning America" and spent several months on grocery shelves in Minneapolis. Unfortunately, Greff did not have the capital necessary to market the product, and he abandoned the venture in favor of the demands of the highway (though he still holds the patent).

North Dakota was one of three states to decline in population during the otherwise booming '90s. Regent once had two grocery stores and three bars, and it was common for farming families to have 10 children. "This state has always relied solely on agriculture, and we failed to respond quick enough when we saw that it wasn't working anymore," Greff says. "It became clear that my small town was going to be dead if I didn't do something."

Despite rumors to the contrary, the Enchanted Highway was not the result of Alan Greenspan's taking hallucinatory stimulants. The idea came to Greff when a farmer placed a makeshift sculpture of a farmer hoisting a giant bale of hay and people began stopping by the side of the road to check it out. North Dakota has its share of similar attractions. Salem Sue, the world's largest Holstein cow, towers above I-94 in homage to the region's dairy farmers. Dunseith houses a turtle made from 2,000 wheel rims and the world's largest buffalo resides in Jamestown. "People are not going to stop for normal," says Greff.

Most roadside attractions celebrate the cultural life of a region or leech onto an existing tourist infrastructure. Greff's Enchanted Highway is a metallic rain dance for an economy to come. Even before the decline in Midwestern family farms in the '70s and '80s, Regent was a town of just 500. In the past three decades, the population has been cut in half as young people moved to larger towns like Dickinson, 40 miles west, or cities like Bismarck and Fargo. Seniors make up the bulk of the citizenry. Regent has not had a police officer in 12 years and its children travel 45 minutes each way to school.

The Enchanted Highway is a community effort. Each of the sculptures sits on private land that Greff leases from local property owners at $1 dollar for 20 years. The funds for the first two sculptures were raised through a series of "family fun" days, bingo nights, card tournaments and raffles. The Lions Club donated nearly $3,000, with other civic organizations and individuals contributing in kind. The highway wouldn't have gotten off the ground without the support of the town, says Brenda Wiseman, manager of Regent's Consumers Co-op. Wiseman has helped Greff raise funds since the project's inception. The first two sculptures priced out at nearly $20,000, which, she notes, "is a lot of money for a town of 265 people."

Roger Warbis of Farmer's Union Oil, Regent's gas station, says people are divided on whether the highway will help revitalize the local economy. "Once you see the sculptures, there's nothing else to do in Regent," notes Warbis, who has seen an additional two or three visitors a day since the highway began attracting attention. "They don't usually buy gas; mostly they come in to use the bathroom," he observes. Nevertheless, his station includes a small gift store that peddles, like most of Regent's other businesses, Enchanted Highway key chains, cups and T-shirts. He has even drawn up plans to adorn the station with metal art. Warbis describes himself as "cautiously optimistic" about the highway's potential.

"When I first started," says Greff, "sure there were people who thought I was nuts. A lot of people still think I am. But once they saw the sculptures getting completed and realized that I wasn't a fly-by-night, then attitudes began to change. No one has ever built a statue to a critic." Jan Webb, executive director of the North Dakota Arts Council, concurs. "Initially I thought he was a bit strange, but after working with him I realized he's just enthusiastic." Webb and others credit Greff for generating publicity for the town in People magazine, the Wall Street Journal, Minnesota Public Radio and the occasional Web site.

But if Greff builds it and they come, then what? Greff speaks of a metal theme park, but he is too busy welding, fund-raising and promoting to strategize. While two new sculptures will go up this year, Greff doesn't think the project will be completed before 2006. For now, hawking Enchanted Highway tchotchkes will have to do for the few local businesses. The Regent Café may get a few more lunchtime visitors and Warbis may sell a few more gallons of gas, but the highway seems unlikely to stem the tide of migration by Regent's youth. Although few question Greff's motives, this town of dogged, "cautiously optimistic" admirers may have produced a visionary sculptor without a visionary strategist to match.

"I've definitely bled the turnip dry here in town," says Greff, whose two most recent sculptures cost a total of $58,000. Greff tapped out his own savings nearly a decade ago, spending the bulk of the money left over from his tearless-onion venture on metal and paint. Currently, state Sen. Byron Dorgan is courting larger individual and corporate donors whose names have yet to be made public. Last year, the highway received $3,000 from the city of Regent as well as grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the North Dakota Arts Council and the Hettinger County job development authority.

With the exception of a one-time gift of $10,000 from Cellular One in 1999, funds have come primarily from grass-roots sources. Civic organizations like the Knights of Columbus, the Lions and booster and commercial clubs have pitched in, as have the city councils of nearby towns. The raffles, carnivals and auctions Greff runs with the support of local business owners usually net him about $1,500 each. "I know there's a person out there who has the money, that can share the dream and see that this will, someday, make money," laments Greff. Until he finds his benefactor, Greff diligently cranks out grant proposals on his typewriter.

At about 50 tons, 90 feet tall and 150 feet wide, "Geese in Flight," Greff's latest work, is set to take off in July. The sculpture features 10 geese silhouetted in flock formation behind a bursting sun. Ever the optimist, Greff hopes the geese will go down in the Guinness Book of Records as the world's largest metal sculpture -- which might save Regent from becoming the world's smallest town.

Shares