Al Reichwaldt thanks his lucky stars that he was able to attend the seventh annual Cracker Jack Collectors Association Convention in Milwaukee June 21-23.

Just over a year earlier, Reichwaldt, then 61 and a 40-year factory worker, was driving north from Milwaukee to his mobile home, two hours away in the village of St. Nazianz. Suddenly the muggy day turned strangely chilly. He'd heard from the postmaster that a bad storm was coming, and when he got home, he went to watch the Weather Channel with a neighbor who lives 50 feet west of him. It was then that the sky went pitch black and baseball-size hail started to pelt the trailer. Reichwaldt was standing 7 feet away from a window when the pane crashed inward. The bathroom sink from his mobile home nearby had slammed through the glass. "Tank Gods I had on my glasses," says Reichwaldt, who grew up on a Wisconsin farm speaking German until first grade. An ambulance rushed him and other park residents to a hospital, where he received 113 stitches.

The thunderstorm, which Reichwaldt calls a tornado, struck with winds of 110 miles per hour. It flattened his furniture, sent his refrigerator through a wall and blew away his electric stove, never to be found. Reichwaldt also owns about 10,000 Cracker Jack toys, which he kept primarily in metal cans in his mobile home. Miraculously, he lost only three tin dog bookmarks.

At the Cracker Jack convention, Reichwaldt -- without a single scar on his baby face -- handed out a special card to other convention-goers. It pictured him as Sailor Jack with his faithful dog Bingo clutching his leg as a funnel cloud looms behind them. The bottom of the card read: "Tornado Al: Cracker Jack Collector."

Everyone in the Cracker Jack Collectors Association knows the words to the 1908 song "Take Me Out to the Ball Game," but not for any love of baseball. It was the line "Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack" that made their beloved confection famous. All serious collectors have items numbering in the thousands. "The more you collect the more you want," they'll quip, a takeoff on the early C.J. slogan "The more you eat the more you want." Often surprisingly vague about how many pieces they have, members can list exactly what they're missing.

Collectibles range in cost from less than a dollar for plastic toys or current paper prizes to more than $1,200 for a Joe Jackson baseball card from 1915. This huge price spread attracts a membership of diverse means. Alex Jaramillo Jr., one of the organization's unofficial historians, wonders, "Why were these paper prizes saved?" He compares them to pressed flowers, tucked away to preserve a memory.

Each year, a representative from Cracker Jack, a division of Frito-Lay since 1997, has given a presentation at the convention. Don Helms, fairly fresh out of graduate school with a couple of years' experience with Doritos under his belt, showed a chart of C.J.'s flat sales. One member complained, "There aren't enough peanuts in the package." Helms confessed that when he took over as associate product manager of the brand four months ago, his predecessor warned him, "You're going to hear this every day of your life," despite Frito-Lay's having increased the percentage of peanuts. And even though Frito-Lay reintroduced three-dimensional plastic prizes, which hadn't appeared for years, people still kvetch that "the prizes are lame."

The collectors also heard from Becky Smith, sales manager of W/S Packaging Group in Algoma, Wis. The company produces paper prizes, typically in lots of 10 million, for Cracker Jack. Smith understood her audience. She held up samples she'd brought along of uncut sheets to give out during a trivia game.

A number of members instinctively oohed, and a low murmur of want started to hum through the room. The walls seemed to close in and the room got warm with all the heavy breathing. Smith even warned the audience that it wasn't worth driving to Algoma for some Dumpster diving because all the paper waste is burned or shredded. At "shredded," someone cried out, "What a nasty word!"

The 170 CJCA members all have their own stories of how they got started collecting, but the trajectory often follows a familiar path. Ann Brogley, the founder and first president of the association, who now owns about 10,000 items, began collecting the inexpensive but visually exciting plastic toys that were primarily inserted in boxes the '50s and '60s. Then she started amassing series of paper prizes. Once you're looking for specific toys, you're hooked. Soon you pick up a few of the metal surprises from the early 1900s. Finally, you see one of the early, fragile paper prizes or premiums and bite the bullet, laying out more than $100 for a single item.

Some people you'd expect to have spectacular collections tend to be Johnny-come-latelies. Cecelia Downs' grandmother worked on the toy line at the Chicago Cracker Jack plant for 30 years. As a child, Grandma Anna always gave Downs C.J. toys, but she didn't save any. When her grandmother died, she left Downs about 100 prizes. At first Downs let kids in the neighborhood play with them and handed out others. Later, she went around the block to try to get them back. She first attended the CJCA convention two years ago to read to the group from her novel in progress about her grandmother's close ties to the other women she worked with on the second shift. Downs came to this year's convention to add a few items to her slowly growing collection. She's up to 200 prizes now and focuses on the items she casually gave away in her youth.

If any one person is responsible for enticing people to collect C.J. memorabilia, it's historian Jaramillo. Rick Magnus from New York blames Jaramillo for what has become "a passion, not a collection." In 1989, Magnus bought Jaramillo's book "Cracker Jack Prizes." Jaramillo, hired as the official Cracker Jack spokesman during the '80s and '90s when Borden owned the brand, wrote the book as a social history. He describes how each decade of prizes from 1900 to 1980 represents "particular people in that particular time." The luscious close-up photographs of the prizes made readers itchy to own them. Larry White, with a collection of about 80,000 items, says people would think, "I'm going to try and get every prize on Page 27."

Convention regular Harriet Joyce was called the "Queen of Cracker Jack" in a 1979 South Bend Tribune article. She's too humble to let anyone in the CJCA call her that, but with more than 100,000 items in top condition, she is the queen. And she's visited more Cracker Jack shrines than anyone.

The C.J. universe is full of unpredictable twists and turns, which might be part of its appeal. Through an ad Joyce placed in a magazine in the '70s, she met John Craig, who designed prizes for Cracker Jack. In 1980, he invited Joyce to join him on one of his visits to the Chicago plant, and she obtained permission to enter the second-floor vault. It was drab inside, with cement block walls and fluorescent lights, but Joyce spent the day on a collector's high going through drawer after drawer of prizes. "I never knew what was going to be in the next drawer," recalls Joyce. Later that year, she met the king of C.J. collectors, Wes Johnson from Kentucky. He, in turn, brought her along when he visited the studio of C. Carey Cloud.

Cloud, born on an Indiana farm in 1899, designed 102 different sets of prizes over 28 years. Hired in 1937, he played a key role when the company stopped importing prizes from Japan during World War II. He had to be inventive, since rationing limited his access to anything but paper for materials. He also designed the first plastic figurines when the company began using injection molds.

Only once did the company have a complaint about his prizes. In the late '40s, some adults thought his plastic sea captain looked like Joseph Stalin. According to Jaramillo, "Rabid anti-Communists ... believed Cracker Jack was being used to propagandize the youth of America." The company withdrew the figure from circulation. Of course Joyce owns a sea captain, worth about $20.

Joyce is a charter member of the CJCA and helped Brogley find other collectors to join. Until the association got going in 1994, people tended to fiercely guard lists of people with whom they traded. This all changed at the first convention. An article in Ohio's Columbus Dispatch explained, "The association has transformed once-hostile hobbyists into a group of friendly competitors scrounging through attics, toy boxes, floorboards, antique shops and flea markets." Brogley remembers witnessing "people scream and hug each other" after they matched up collectors they'd known only by their handwriting or voice.

Each convention has had its defining story. Larry White, a Massachusetts antiques dealer, often plays a key role. Since the publication of his Schiffer price guide, "Cracker Jack Toys: The Complete, Unofficial Guide for Collectors," in 1997, and then 1999's "Cracker Jack: The Unauthorized Guide to Cracker Jack Advertising Collectibles," he has been a familiar name to any C.J. collector. And yet his nickname in the CJCA is "Larry the Loser."

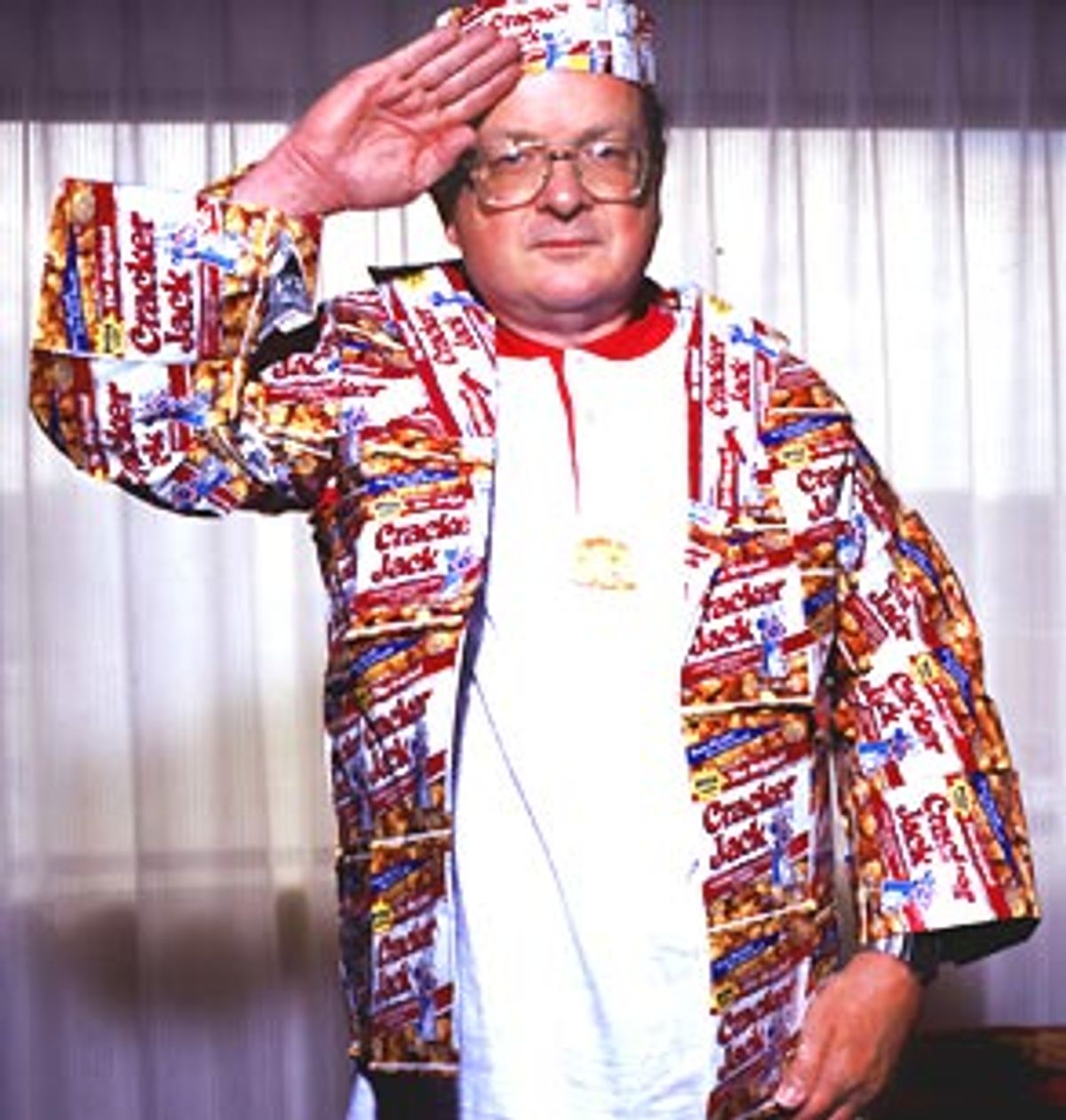

At the first convention, White and a number of other members arrived late to the banquet. They decided to sit together at a table in the back. During the raffle, the table mates realized they were jinxed and had won nothing but a little bottle of bubbles, which wasn't even a C.J. item. With nothing else to do, they started blowing bubbles and pounding on the table in frustration. They had such a good time they decided to sit together at the second convention banquet too. White was supposed to give a slide presentation, but couldn't get the projector to work. He was instantly dubbed "Larry the Loser" and the table, now an annual fixture, the "Losers Club." Last year in Dallas, White outdid himself. He came to the banquet wearing a red ten-gallon hat, a sports jacket he'd made out of Mylar C.J. bags and a tie with caramel-coated popcorn glued to it. The popcorn slid down the tie throughout the humid evening.

For 2001, everyone will remember the grand finale of the magic show. That morning, Mary Rowe returned to her room after breakfast to find that someone (perhaps a suspicious-looking person some had seen lingering in the hall with a vacuum cleaner) had taken $800 from a bag. That afternoon, at the end of a Cracker Jack-themed magic show, the young magician looked around the room for a volunteer. He selected Rowe, who came to the front of the room.

The magician asked her for a dollar; she shook her head in embarrassment. Someone in the front row handed him a dollar for her. He folded it up into a tiny cube and blew on it, and when he opened it up, it was a $100 bill. He handed it to Rowe, along with four more he pulled out of the air. Rowe cried, along with everyone else in the room. In six hours, the membership had accumulated $500 for her. Some people didn't know about the fundraising effort, but rolled bills continued to pass from hand to hand. By the time Rowe left, she had $770.

But Magnus sits with shoulders slouched after the magic show. "This is a hard day. We'll all be leaving soon and won't see each other for another year. This is not the real world here. Here, if you get hurt, people ask, 'What can we do to help you?'"

Shares