Almost three months after Sept. 11, there are still no stupid ideas in the fight against terrorism. We can celebrate the apparent fall of the Taliban, but it won't be long until we remember that it wasn't the Taliban who attacked America. It's hard to imagine what a broader, enduring strategy might be, and the government has stopped just short of coming 'round the house looking for ideas. In this spirit, we owe it to ourselves to consider some less conventional approaches. The government's already hired Hollywood for its creative vision; why not enlist the rest of us for our tireless -- and suddenly valuable -- rumor mongering?

We saw Sept. 11 shut down almost everything; one of the few institutions to thrive immediately afterwards was the urban legend. CNN couldn't report them fast enough, and we took it upon ourselves to pass along stories: the child who predicted the attacks, the FBI agents who had advance warning, the man who miraculously "rode" the falling World Trade Center safely to the street. We're still spreading stories, albeit less frantically, and it doesn't take a business degree to recognize this energy as an untapped resource.

My father recently told me about the friend of a friend in line at a 7-Eleven in Rappahannock County, outside Washington. This friend found herself behind another customer, a man of Middle Eastern descent, who was short one dollar.

The woman handed him a dollar from her purse. The Middle Eastern man reluctantly accepted the money and thanked the woman profusely. She said he was welcome. He paid and left. Minutes later, in the parking lot, the woman discovered that the man had waited for her.

"You have been incredibly kind," he said, "and I would like to send you the money as soon as I return home."

"Don't be silly. No need to send me anything," she said.

"In that case, please allow me to tell you something." He lowered his voice. "Stay out of Washington tomorrow."

I told my father that the story was an urban legend, and that it had not only circulated the country with various geographical permutations -- Rappahannock County; New York; Boise, Idaho; Orlando, Fla. -- but had made the rounds in other terror-plagued countries long before Sept. 11. In England, a version of the encounter replaced the Middle Easterner with a grim Irishman, and so forth.

As memes go, the myth of the benevolent Arab transmits exuberantly. The idea of an almost-remorseful terrorist sounding a warning to one lucky American resonates so deeply that we willingly overlook its inconceivability. As Barbara Mikkelson points out on the Snopes Urban Legends Web site,

In real life, terrorists do not share their plans with those who might or might not end up caught in them because the potential cost of a warning -- the disruption of their schemes -- is deemed far too high. Terrorists view those who die as collateral damage, and although they may regret a particular death more than another, the potential for that regret does not sway them, not even to the point of issuing a small caution to an especially favored innocent.

Other variations on the benevolent Arab tale are equally implausible, like the one where a young Middle Eastern man warns his ex-girlfriend not to fly on Sept. 11, or to enter any American malls on Halloween. The throng of legends that followed the attacks have been well-documented, and well-dissected: We divide our time between picturing the next attack and imagining its prevention; the intersection we've devised is a lone, human terrorist. At the local 7-Eleven we find a way out of what otherwise appears hopeless. Give an Arab a dollar and we might just live a long, happy life.

"We will not give in to exaggerated fears or passing rumors," George Bush said Nov. 9 in his speech in Atlanta. This is the wrong tack; what Bush fails to understand here is that the benevolent Arab and other passing rumors could help us win the war.

How many Muslims worldwide will follow bin Laden into jihad? How many nations will continue to harbor terrorists within their borders? How many 13-year-olds in Saudi Arabia will take up bomb-making? The so-called war on terrorism will be won or lost on these questions, and with an intelligent, creative campaign of information management, we can retain some control of them.

Enter the urban legend. Observers of folklore, fables and other varieties of cultural myth know just how significant this kind of information can be in times of unease. These stories reflect anxiety, model behavior and often empower the teller all at once -- that's a lot of function for any yarn. In the case of the benevolent Arab, the last-minute warning suggests a way out of the terror, if only fantastic. As Mikkelson writes, "society has a strong need for rumors of this nature because they tend to reduce the sword of Damocles hanging over all of our heads to a mere butter knife."

America is a nation of sophisticated narrative devices. The stories generated by our various commercial voices are designed to make money, after all, and consequently know how to stick in our brains. Our movies, even the dumbest ones, are startlingly compelling, and so are our advertisements. Our pop songs are catchy and our TV dramas affecting, if not memorable. We know how to plant ideas in heads, because that's where every future financial interaction germinates.

Our military leadership also appreciates the value of seeding certain thoughts -- over the years we've dropped enough leaflets to smother bin Laden many times over. But like even the most compelling movie, TV show or advertisement, the impact of any propaganda message is limited by the legibility of its source; propaganda looks like propaganda. We sniffle at the schmaltzy ad for long-distance phone service, but we don't sob, and this is partly because we know who's behind it. Same with a cautionary TV drama about, say, drug abuse: Even at our most porous moments, we have pride enough to keep the manipulative TV people out of our inner selves.

But when there are no TV people or ad execs, when the message we're getting comes instead from our own friends, co-workers and family, we don't put up the same guard. A story received not top-down but laterally finds us powerless to limit its resonance. There's no narrative tyranny, as it were -- just folks keeping other folks apprised. What better vehicle for spreading information in hard-to-reach places?

It's not just because they're good stories that urban legends spread like wildfire; if plot were the only requirement, we'd spread just as many e-mails recounting those dopey but compelling "General Hospital" story lines. No, much of the allure seems to come from the telling itself. As folklorists point out, it can be downright empowering to help spread one of these tales, particularly when the tale bears a warning: The teller just might be saving a life. In times of war, data and heroics are both in high demand -- possibly more so than accuracy. Not only is the medium the message with urban legends, but the medium is readymade for war.

We've seen the technology work. Decades ago, a story began circulating about a young couple parked out in the woods -- those woods right over there, in fact. According to the story, things were starting to get steamy when the girl thought she heard the crunching of pine needles outside the car. The guy dismissed it, and they got back to necking. Then she heard it again, this time closer. The guy dismissed it, and they got back to necking. Finally, she heard it again and insisted that they drive away. They did, and when they got home, they found a bloody hook hanging from the door handle.

The primary function of the hook story, like all urban legends, is to entertain. The tacit function, however, is to nip necking in the bud: We tell the hook story at campfires and chances are, we don't pause over its cautionary implications. But the work of the message has been done, and it's not hard to imagine at least one pair of young lovers thinking twice before easing the Chevy into the evergreens.

It's no coincidence that the girl's chastity saved her life -- these tales almost always conflate morality with horror, or in other cases, good fortune. An ordinary decision is made (let's drive away, I should lend the Arab a dollar, etc.), and the consequences inevitably prove extraordinary. Real life rarely entails such immediate reciprocity, but in the fantastic universe of simple moral fables, instant karma will actually get you.

Just as appealing as a clear and knowable moral world are the bones beneath it. Successful urban legends, like all memorable allegories, rely on a few dependable narrative devices. In the bloody hook story, we remember the pine needles. At the 7-11, we remember the terrorist's eerily insistent gratitude, his waiting in the parking lot. In every legend, there's something we're left chewing on, long after the telling. Having gained entrance with an initial bit of intimacy -- all begin by establishing the reassuringly brief chain of origin -- the story proceeds to put its hook in us, so to speak.

As with smallpox, dissemination of our strategic urban myths would be carried out by the targets themselves, oblivious to what they're spreading. What starts with an e-mail in Brussels, or a whisper in Peshawar, will move over borders and into caves faster than we can load peanut butter into cargo holds.

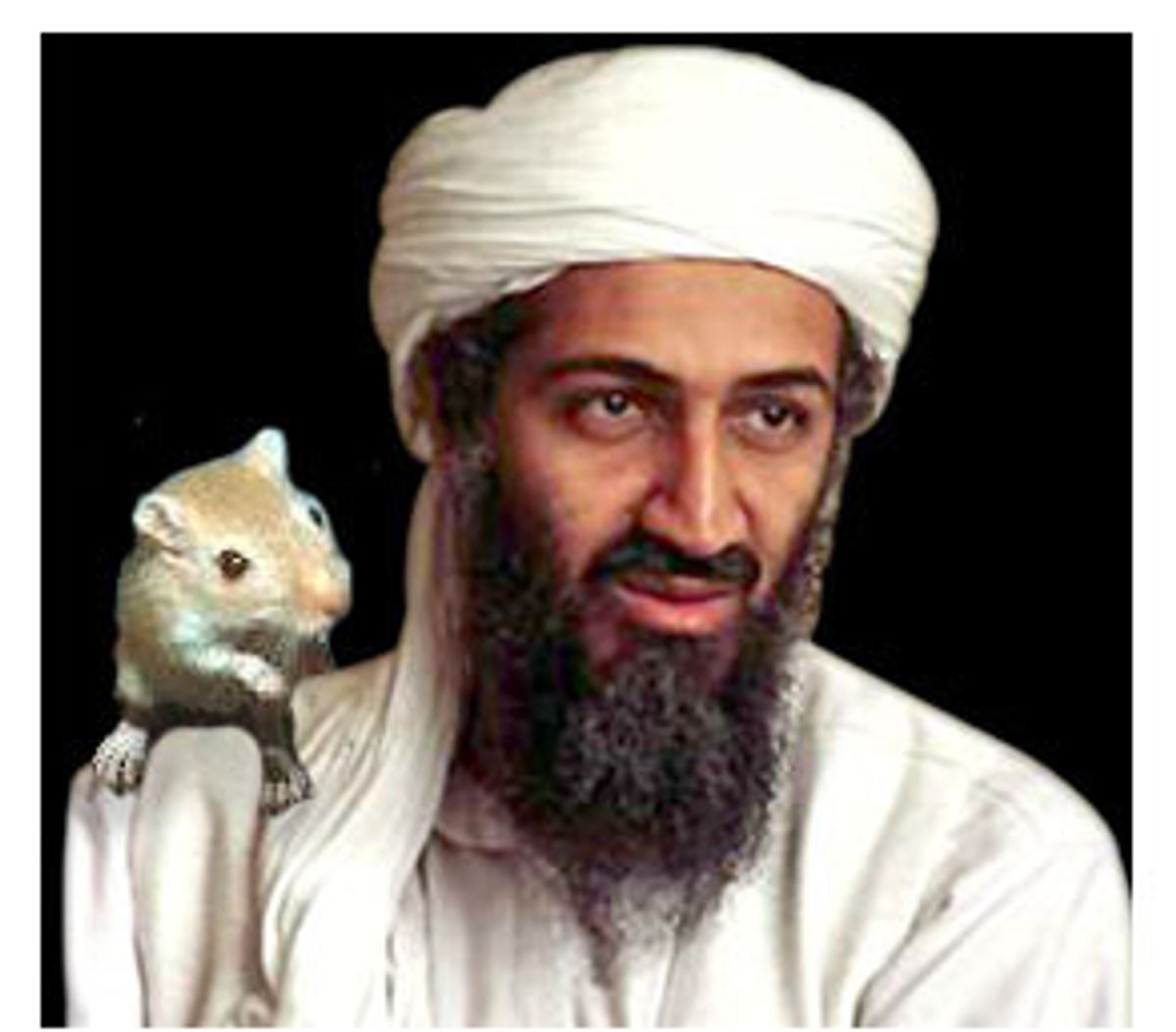

It's time for Washington's idea people to study the conventions of the urban legend and crank out a few of their own: stories about misfiring Stinger missiles, creepy noises outside caves, perhaps even bin Laden and a gerbil. These fables can exaggerate our intelligence capabilities, expand on a few frightening prison myths and reward the virtues of a gentle, terror-free life. Indeed, they can be positive, too: The West isn't evil after all. We have our own black-eyed virgins, e-mail chain letters can solve cancer and in American convenience stores, strangers lend you money. In fact it happened just the other day.

Shares