Generally, I'm happy to leave it to Jonathan Bernstein, whose blogging is often cross-posted here, to point out the inanity of Matt Bai's political analysis. But after reading Bai's latest effort in the New York Times, I can't resist.

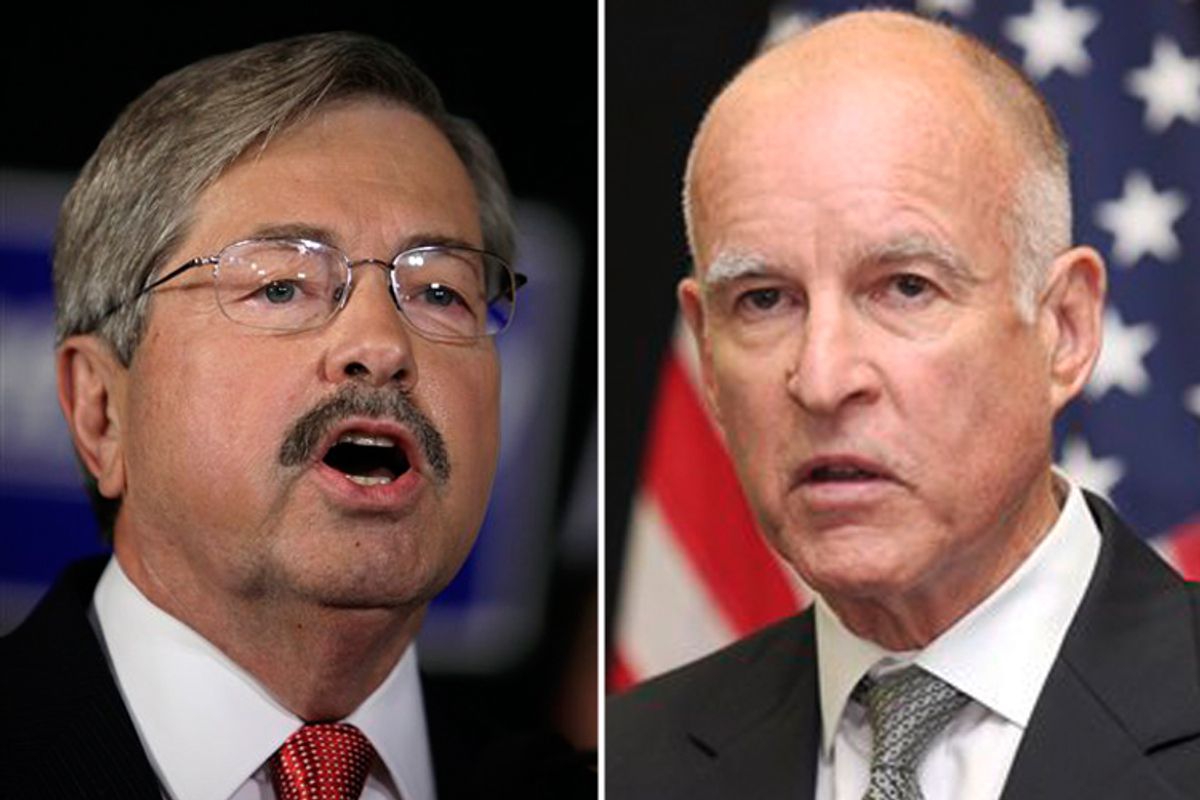

He focuses on a mildly interesting aspect to this year's elections -- a high number of former officials, some of them long-departed from the political stage, are back and running for their old jobs: Jerry Brown in California, John Kitzhaber in Oregon, Dan Coats in Indiana, Roy Barnes in Georgia, and Terry Branstad in Iowa. I guess you could also include Maryland's Bob Ehrlich, a former governor who is running against Martin O'Malley, the man who ousted him in 2006.

Anyway, as I said, it's an interesting footnote, and sort of a fun one, too: I love the idea of Jerry Brown being back in the political big-time. But Bai takes it and turns it into a national psychological crisis -- proof that voters, frightened by the rocky economy and their novice, "post-Simpsons" president are seeking comfort in the arms of political father figures:

So why the sudden success of political nostalgia? The most obvious explanation has to do with the economic morass. When a moment is as bad as this one, there is probably a tendency among voters to conflate past moments in the life of the country, on one hand, and the politicians who personified them, on the other. If by comparison the 1980s seemed so much easier and more promising to Iowa voters, then why not just go hire the guy who ran the state then? Surely he’ll know what to do.

This probably explains the recent burst of Clinton envy, too, with both Democrats and Republicans expressing affection for the 42nd president and his administration...

Seriously? Let's dispense with the second part of that excerpt first. The "sudden burst of Clinton envy" is actually very easy to explain, and it mainly has to do with the fact that Republicans no longer see him and his wife as their chief enemies -- a role that the Clintons played from 1992 through the spring of 2008, when Hillary lost out to Barack Obama for the Democratic nomination. Without the GOP challenging his motives and his character every five minutes, and with the media now treating him as a former president (rather than the scheming spouse of a would-be president), voters are now free to judge Bill on his personality -- which they've always liked.

Bai's bigger claim, about the supposed significance of ex-office-holders running in this climate, is just as absurd.

There's no great mystery, for instance, why Brown is now leading (slightly) in California's gubernatorial race. The explanation starts in 1998, when he began his (latest) comeback by winning election as Oakland's mayor, a position he used as a springboard to the Democratic nomination for state attorney general in 2006. And since the political climate of 2006 was exceptionally strong for Democrats, Brown had no trouble winning the job in the general election. And once he was A.G., he was perfectly positioned to seek the governorship, which -- thanks to term limits -- would be open in 2010. He received another break when, Antonio Villaraigosa, the Los Angeles mayor who might have given him a tough run for the Democratic nomination, decided in the face of some unflattering news stories about his personal life and ethics, not to run. Dianne Feinstein, who might have intimidated Brown out of the race, also opted not to jump in. That left Brown to face Gavin Newsom, the San Francisco mayor -- who quickly realized, for a variety of reasons, that it would be wiser to drop out and run as Brown's lieutenant governor candidate.

Having secured the Democratic nod, Brown was thrown into a race with Meg Whitman, a free-spending Republican who -- initially -- benefited from 2010's strongly-anti-Democratic tide. But Whitman has not held up well under the spotlight, particularly in the wake of revelations that she'd employed an undocumented woman as her family's nanny, and has now fallen several points behind Brown. Thus, Brown is now likely to reclaim the governorship. This doesn't tell us that Californians are clinging to him for comfort; it tells us that he spent the last 12 years positioning himself well for this moment -- and then caught a few breaks. This could happen to any politician.

We could tell similar stories about the others Bai cites. Their previous service only helped them in that it provided them with a key advantage in name recognition, forcing other would-be candidates -- especially in primaries -- to back down.

Consider the case of Coats. Hardly a beloved pol in Indiana, he opted not to run for a second full Senate term in 1998, figuring he'd lose to Evan Bayh. But with Bayh retiring this year, Coats jumped in the race -- and generated remarkably little enthusiasm. In the primary, he snared less than 40 percent of the vote, but was helped by the presence of two conservatives -- Marlin Stutzman and John Hostettler -- who vied with each other for the right's loyalty. In other words, Coats caught a big break. And that's all he needed, because in 2010 in Indiana, a Democrat is just not going to win an open Senate seat. So Coats is on his way to returning to the Senate. This doesn't mean he's comfort food for Hoosier voters, though. It just makes him an average politician who is running for office under favorable circumstances.

To reinforce his case, Bai also offers this:

Such candidacies would seem to contradict one of the more sound truisms in politics, which is that campaigns are always more about the future than they are about the past. Think back to 2002, when Democrats, mourning the loss of Senator Paul Wellstone in a plane crash, tried to install Walter Mondale as a sentimental choice in his place. Minnesota’s voters felt badly about the tragedy — but not quite badly enough, it turned out, to revisit 1984.

So the idea is that it takes a special kind of year -- like this one! -- for retreads to win at the polls. But it's funny that Bai should mention 2002, because that's the same year that -- while Mondale was losing in Minnesota -- another former senator, one four years older than Fritz, was winning in New Jersey. That would be Frank Lautenberg, who'd previously served three terms and who was recruited out of retirement to replace the scandalized Robert Torricelli on the ballot. Lautenberg beat Republican Doug Forrester by 10 points.

Bai also tries to connect it to 2012:

For Republicans, that impulse to relive the past could have serious implications for 2012, as they seek a compelling contrast to Mr. Obama. Consider what happened after the election of Mr. Clinton, the first boomer president. Similarly energized then as they are now, and eager to exploit the same kind of cultural friction, Republicans in 1996 nominated the former senator Bob Dole, who, at 73, was an icon of the World War II generation.

“Let me be a bridge to a time of tranquillity, faith and confidence in action,” Mr. Dole implored in his acceptance speech in San Diego that year. Voters preferred Mr. Clinton’s “bridge to the 21st century,” instead — and by a wide margin. Americans may stutter-step at the doorway to generational change, but in the end, we almost always barrel ahead.

Funny he should mention 1996! Under Bai's theory, the country recovered from the psychological trauma it had felt in 1994 and was not in the mood to elect fogies by '96 -- hence, Dole's failure. But while Dole was losing to Clinton, West Virginians elected as their governor a man named Cecil Underwood -- a 74-year-old who had previously served as governor....from 1957 to 1961. Clinton, by the way, won West Virginia over Dole by 15 points. So, to Bai's point, it seems that West Virginians were psychologically traumatized and in need of a daddy figure when they thought about Charleston. But when they turned their attention to Washington, they wanted to "barrel ahead."

Shares