After my bad experiences in the sleazy hostess clubs of Roppongi and Shinjuku, I was ready to give up. English teaching was starting to look alarmingly good, but my South American boyfriend disagreed. "You should try it one more time. You were born to do it -- at least for a little while," he said, stating what I knew, deep down, to be true. It wasn't a compliment but a fact: I was born to hawk fictional devotion, transforming my insecurities into fatal charms. (For his part, he had spent enough years in Japan to know that bizarre employment like this was part of the territory, and to appreciate that the "true" love of a hostess shouldn't waste his time being jealous of her customers.)

So I answered an ad in Tokyo Classifieds, an English-language weekly, that took me to the Akasaka district. Apparently I was extremely lucky: Verdor, an exclusive members-only hostess club famous for being staffed strictly by foreign girls, hardly ever advertised. For recruits it relied on the pickings of talent scouts and the attractive friends of employees. Midori, the club's owner and "mama-san," took one look at me and immediately began explaining the club's complicated system of salary and bonuses.

"Excuse me, but does that mean I have the job?" I asked, somewhat confused at how easy it had been. "Oh, sure," Midori smiled. For a while I thought it was my Japanese skills and my offbeat style of dress -- akin to Midori's own -- that won me the job.

Soon, however, I realized that Midori, a clever businesswoman, often took a chance on girls who seemed reasonably attractive and intelligent, even if they didn't have their own customers. (In the hostessing business, having your own customers is like having a Harvard MBA.) If the new girls didn't work out -- that is, if they didn't bewitch enough men during the first week or two -- she was just as ruthless about firing them.

Verdor has been around for 20 years and continues to flourish as countless other hostess clubs close their doors, victims of the struggling Japanese economy and the slashing of corporate expense accounts. One reason for Verdor's success is its mama-san, Midori. Traditionally, all hostess bars had a mama-san -- often, but not always, the club's owner, a woman who was part nurturer, part impresario -- to keep things running smoothly between the women and the customers. Women come and go, customers too, but the mama-san, often a former hostess herself, understands the business and the hearts of men as few people do.

At Verdor, Midori was the much beloved star. Customers from 15 years back came to marvel at her Cirque du Soleil-style outfits and her husky voice before turning to the hostesses. Her voice was so low and her style so wild that a common rumor among her less loyal customers was that she'd undergone a sex change.

Despite this, there was something about Midori that was as comfortable as the rest of her was unconventional. Mama-sans have to have a nurturing personality. Although they are expected to be stylish and classy, they are almost as desexualized as wives in Japanese society. Men come to the mama-san for coziness and a touch of panache, and to her hostesses for titillation.

With me, as with the other girls, Midori was kind but somewhat distant; she left me alone to do my job as long as I was making her money. And I was. But it's tricky: Of course the mama-san wants her hostesses to be successful, since her own income depends on it, but she doesn't want them to be too successful.

The relationship between my friend Anna and her mama-san, Toni (at another high-class club), is a good case in point. Toni was an exotic-looking former hostess from Spain who had recently been named the mama-san -- but not the owner -- at Anna's club. This tenuous position of power made Toni nervous, even though she had been incredibly successful during her 10-year career as a hostess. Because of her anxieties about success as a mama-san, and as an aging woman in the business, she latched onto Anna, who was kind and loyal -- a rarity among hostesses. "You're the only person I can trust," Toni repeatedly told her.

The problem was that Anna couldn't really trust Toni. While it is typically a mama-san's job to introduce her long-established customers to new women -- her younger, prettier hostesses -- Toni was reluctant to let Anna go out to dinner with them alone. She'd arrange to chaperone, and this left the customers disgruntled and Anna frustrated, because her mama-san was keeping her from making money rather than helping her. The customers interested in Anna wanted to see her alone, and when they couldn't, some of them stopped coming to the club.

This, of course, only made Toni panic more, and she grew even more possessive of her remaining customers. Finally Anna decided to move to another club. "Please don't take my customers with you," Toni begged, somewhat unreasonably, because of course Anna had to build up a clientele at her new club to impress the owner.

Her new place did not have a mama-san. "Thank God," she told me. "They're more trouble than they're worth."

In the end, Toni lost about three steady customers who switched from her club to Anna's. Toni was bitter and resentful, and became even more so when her club went bankrupt. She's back to being a mere hostess again -- and Anna's having a ball.

This is a worst-case scenario of the mama-san/hostess tension, but it's always difficult when a lot of women are competing for men, love and money in a space about the size of an American living room.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Until recently Ginza was the undisputed center for high-level entertainment in Japan's capital, but these days Akasaka is beginning to outstrip it, becoming the preferred playground for the political movers and shakers in Tokyo. Home to some of the city's best hotels and one of its four major entertainment districts, Akasaka masks behind its modern façade a world of tradition in the form of manicured Japanese gardens, tiny temples and meandering side streets jammed with restaurants. It is also one of the few neighborhoods in Tokyo that still boasts geisha clubs. Until two years ago it was the site of an annual public dance performance by geisha and maiko (apprentice geisha).

At a place like Verdor, the hostessing system is more complicated than it is at clubs in Roppongi or Shinjuku. At the most basic level, customers pay to drink with young women at a club that's open from 8 or 9 in the evening until 2 or 3 in the morning. They come most often in groups, particularly with co-workers, but if a man is really smitten with one of the hostesses he will probably come alone or with her.

The more smitten he is, the more often he will come, and therein lies the game -- a rather expensive one. At Verdor the men had to pay $150 per person for the first hour ($200 if they arrived with a hostess whom they had just taken to dinner -- and we're not talking McDonald's -- on a system known as "douh an") and $100 per person for each subsequent hour.

The drinks are extra (though most regulars purchase a bottle, usually of whiskey, to last them for several visits), as are "requests" for a particular woman to sit at your table ($20-$30 per request). Clubs in less prestigious neighborhoods are generally cheaper, but most Ginza and Akasaka establishments average about $100 to $200 an hour. Prices are somewhat reduced from 10 years ago, before Japan's economic bubble burst.

But the prices can be higher. At some hostess clubs in the Gion district of Kyoto, Japan's ancient capital, men might ask the mama-san to order geisha or maiko to supplement the hostesses' company, but it costs them dearly: $1,000 per hour to drink with one maiko or $500 per hour for one geisha, in addition to the club's normal fees.

The environment at Verdor was hypercontrolled: Midori decided which hostess would sit with which customer, and the women had to pay attention to how they greeted and took leave of the men, poured drinks (the only serving they do, since waiters bring any food ordered) and bowed. Amid this charm school rigor, I spent my first month in constant terror of doing or saying the wrong thing. Cultural differences are no excuse for crossing taboos in the most exclusive hostess clubs, where things like habitual leg crossing (considered vulgar) can get you fired.

And karaoke singing is de rigueur at this kind of place. Aside from drinking, talking and flirting, the main entertainment is singing, by both the customer and the hostesses. Karaoke is taken seriously in Japan: Some men take private lessons to improve their skills, and one of Verdor's regulars -- a CEO and a cocaine addict -- supplemented the club's already sophisticated sound system by bringing his own specialized microphone and echo box. Other clubs have more lively forms of entertainment, including live bands, dancers and strip shows. But the traditional hostess club is far more bare-bones in its approach.

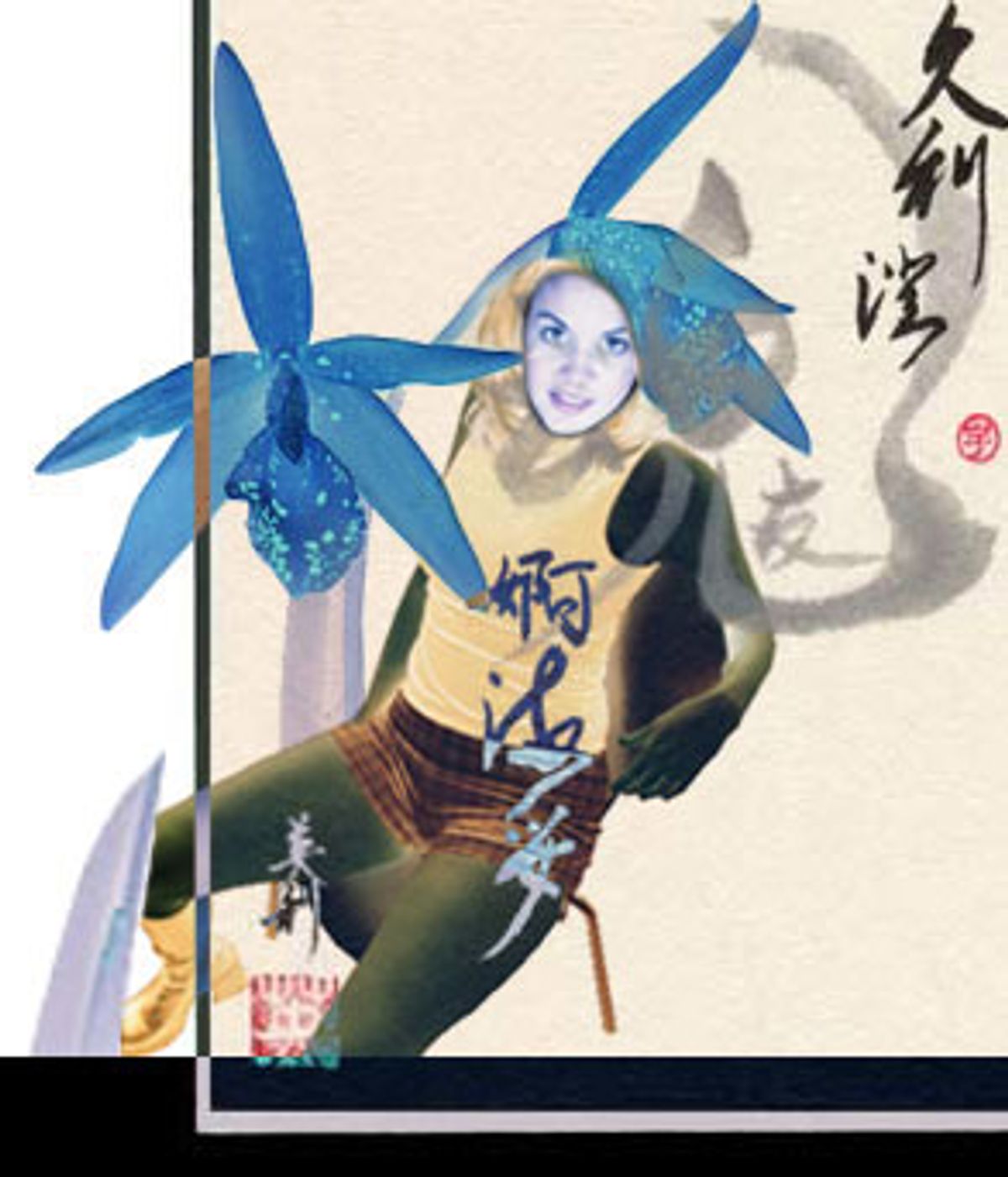

Which makes it even more inexplicable to a Westerner why a man would pay so much (the average is $500 to $600) for seemingly so little. The toniest places (the ones that charge the most) don't offer perks like strip shows or live bands. Instead, they are simply tasteful, quiet oases in the chaos of Tokyo, full of velvet couches, expensive orchids and impeccable service.

In joining Akasaka's "flower and willow world," I thought that my luck had finally changed. I had at last found a club whose customers, for the most part, liked intelligent girls. My most effective weapon was neither my blond hair nor my long legs but, rather, my ability to whisper classical Japanese poetry into my customers' ears and concoct silly haiku with them on paper napkins.

At Verdor, the girls were handpicked by Midori to create an eclectic group of young women. At any given time, the club featured a dozen girls from around the world. While I was there we had a Brazilian samba dancer, a Lithuanian jazz singer, two British students, some part-time models from Canada and the U.S., an Australian artist preparing for her first international exhibition, a Romanian ex-engineer and a New Zealander who was opening a bar in Roppongi with one of her customers. Most could speak at least a little Japanese, a few were fluent, but a couple of girls spoke none at all.

Fortunately for them, many of the customers spoke English -- enthusiastically if not correctly. In any case, not understanding Japanese can be a blessing, at times, particularly when the men begin to talk among themselves about matters better left to the imagination.

"What are they saying?" Sherry, a British hostess who understood little of the language, would ask me.

Our charming customer might be in the middle of commenting on the hardness of his penis, the size of another hostess' breasts or how many times he'd had sex the week before.

"You don't really want to know," I'd assure her. Most of the girls were in their mid- to late 20s -- a little older than average for top clubs. But this was because the majority had worked in other specialized fields, and while they were not trained in the traditional Japanese arts, they all had at least one talent or special feature that, much as with geisha, helped them to quickly garner their own customers in a cutthroat business. And this was essential, because if they couldn't attract any patrons, they'd be fired within the first few weeks, banished to the suburbs for less well-paid work as English teachers.

Once we had customers, however, our problems really began. At some moments I found myself wishing that we all were prostitutes. Faking an orgasm has got to be easier than faking love. And, I think, far more honorable.

Part 4: The art of being in love, when you're not.

Shares