Overcoming embarrassment is no small thing in England, a country that has always made avoiding it a national pastime. The West End's longest-running comedy, "No Sex Please, We're British," centers on the mortification of a bank clerk who finds himself mistakenly put on a pornographic mailing list. England has always been mocked by its continental neighbors for its prudery (America is considered so prudish, of course, that it merits only disdain), but perhaps for this reason the British also have a long and grand tradition of ribaldry. They are probably funnier about sex than anybody, precisely because they are so embarrassed.

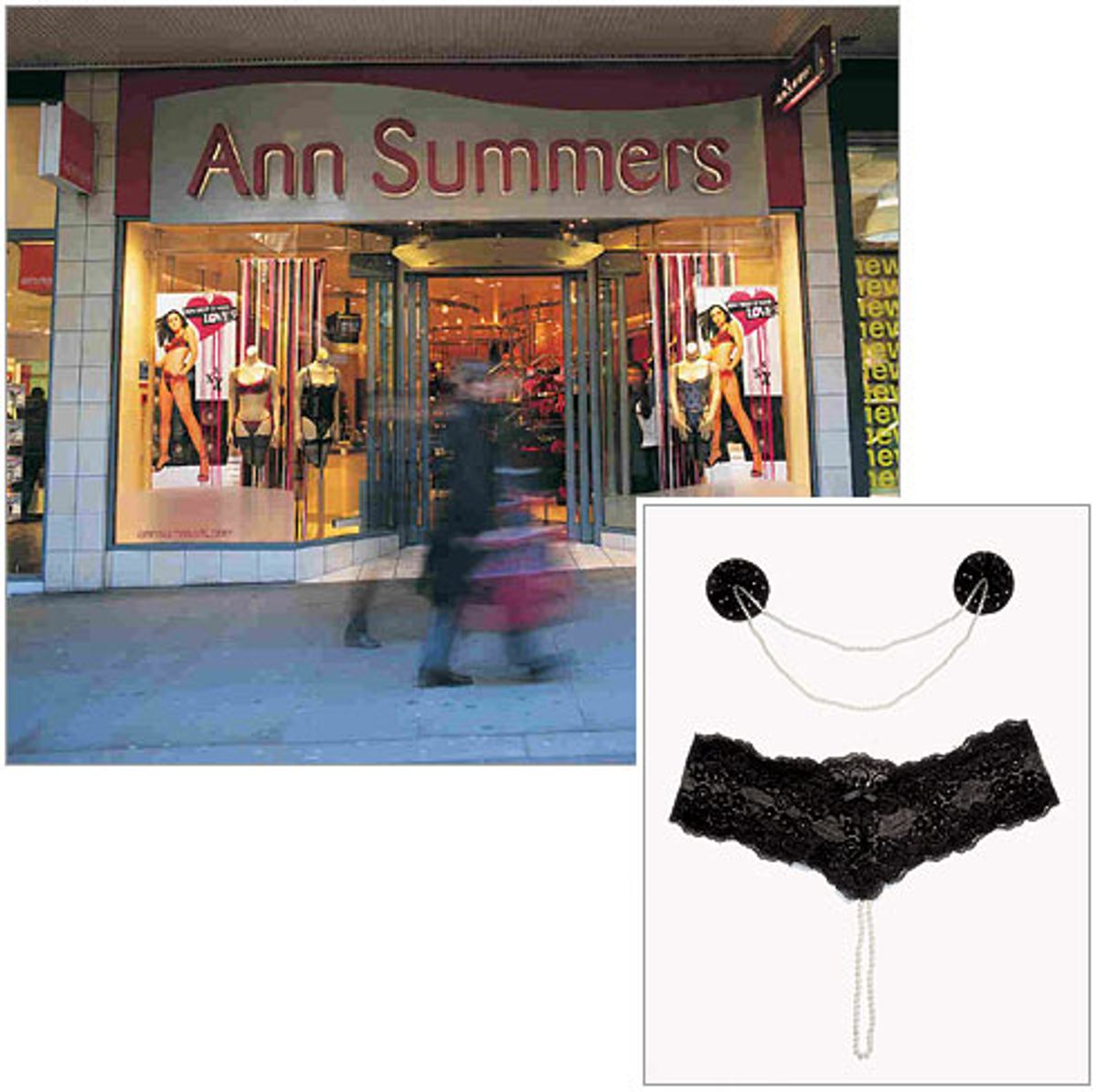

Which is why any Brit attempting to transform a business stocking vibrators, strap-ons and anal beads into a cheery retail staple as commonplace as the Gap would do well to present it as good cheeky fun. And that's exactly what Ann Summers, a massive chain with more than a 100 bright, bustling stores across the U.K., seems to have done. Ann Summers sells 1 million vibrators a year, and has launched a real trend; Selfridges, the hottest department store in London, featured luxury-sex-brand Myla's vibrating toy the Bone (which retails for 199 pounds, or about $360) in its Oxford Street holiday window display, and Sam Roddick, daughter of Body Shop founder Anita Roddick, recently opened Coco de Mer in Covent Garden to sell some more. And the U.K. edition of Good Housekeeping launched its science section last fall by subjecting vibrators to good old Good Housekeeping product testing.

"It was very much a zeitgeist thing," Lindsay Nicholson, Good Housekeeping's editor in chief, says. Nicholson pointed out that a sex survey early in 2002 revealed that 50 percent of the magazine's readers would happily use a vibrator. Ann Summers' cotton-candy-colored Rampant Rabbit -- so well loved by Charlotte on an infamous episode of "Sex and the City" -- was the most highly rated product. "Embarrassment," Nicholson said, "should not get in the way of good information."

That sort of thinking hasn't quite made the leap across the pond. I asked the editor of the American edition of Good Housekeeping, Ellen Levine, if she had ever considered doing product testing on vibrators for the magazine. "It would not be an appropriate topic for the U.S. Good Housekeeping audience, let's put it that way," she said diplomatically. She had not heard about the U.K.'s feature. She asked an assistant to get ahold of it for her. Is the readership for Good Housekeeping so different in the U.K. than in the U.S.? I asked. "A lot of things happen in the U.K.," she explained, "that could never happen here." So it would seem.

Ann Summers stores hum with fun as well as with battery-operated devices, and it's largely because CEO Jacqueline Gold, widely regarded as the founder of English women's current mechanical feast, removed men from overt participation in the equation. A sort of harmlessness bathes even the most graphic items Ann Summers offers, perhaps because women still aren't taken all that seriously as sexual subjects. (When I visited the Oxford Street Ann Summers store, for example, I actually found myself thinking that the Purple Penetrator -- a strap-on 6-inch dildo with a vibrating "bullet" to provide clitoral stimulation to the wearer -- was kind of cute.) Gold was also savvy enough to fill the front of every Ann Summers store with Victoria's Secret-type lingerie: naughty but nice. The message is clear: Seedy is men selling sex to other men, or women selling sex to men, but not women selling sex to other women. When that's the case -- even if Purple Penetrators are on the shelves -- sex is safe enough to sell right next to Nine West.

Walk into any Ann Summers store and it's obvious that it couldn't have happened here any other way. The difference between the ambience of an Ann Summers shop and the kind of sex shops you still find in London's SoHo (where sex shops of the pre-Disneyfied-Times-Square sort abound) is like the difference between Chippendale's, where beefy men in G-strings cavort around stage and pretend to eat-out velvet pillows while women hoot, giggle and clap, and strip clubs for men where, if there is hooting and clapping, there is no giggling, and horny concentration hangs thick in the air.

It is possible that Gold was especially prepared to grasp this stunningly profitable concept (Ann Summers did $250 million worth of business last year, and is projecting a 25 percent increase for 2003-'04, making Jacqueline Gold one of the U.K.'s highest-earning women), because not only did she grow up a multimillionaire's daughter, but her father became a multimillionaire by selling porn. In 1979 Gold chose to join the family business and soon Ann Summers, a two-store afterthought in her father's empire with a 90 percent male customer base, caught her eye. Gold knew, perhaps all too well, that the vast majority of British women would never be seen entering its doors, but she wanted them to. So she devised a brilliant strategy for paving their way: She recruited Ann Summers party planners and let women all over the country get to know the products and the brand in the privacy of their own homes.

Twenty years later the party-plan business is still going strong -- Ann Summers received a tremendous boost when it was made public that Zara Phillips, Queen Elizabeth's granddaughter, had hosted Ann Summers parties at her mother Princess Anne's home at Gatcombe Park. Gold estimates that 4,000 parties take place every week. But the mainstream success of the stores is even more striking, and that boom took longer to develop. In 1997, there were still only 12 franchises in the U.K.; since then 95 stores have been added, and expansion into Europe has begun. "There has been resistance from local government," Gold told me in an e-mail, "landlords, etc., but we have managed to overcome all of this, and now landlords are ringing us up desperate for us to open in their shopping centres, as we are a recognized brand!"

Clearly, despite all the credit Gold deserves for creating, as she puts it, "a safe and female-friendly environment on the high street where women can be adventurous and buy sexy lingerie and sex toys," larger cultural changes in the U.K. over the last five years have benefited her greatly by exponentially increasing women's comfort with what she's selling, and as a result their demand. What's different? The notion of vibrator as accessory, as opposed to vibrator as tool for orgasm (or is it orgasm as accessory?), came up in various forms in my investigation of vibrator zeitgeist. (Nicholson chose the adjective "glossy" to describe the image vibrators currently enjoy.) And none of the recent entrants to the vibrator market epitomizes this better than Myla, a newcomer in 2001.

"We are a luxury sex shop and we are targeting women," co-founder Charlotte Semler told me, "but we do it in a way that is about fashion as much as sex." Myla, whose founders gladly admit learning a lesson from Jacqueline Gold, also escapes seediness because it is women selling sex to women. It can resist bawdy cheekiness, however, by targeting women of a certain sort.

Semler is fond of saying that when she and her partner, Nina Hampson, began exploring the sex-shop business, it was the only market she'd ever looked at where the minority was better cared for than the majority. "If you're into freaky sex or kinky sex -- or you think sex is very humorous or very dirty -- you are extraordinarily well catered for," she said. According to Semler, Myla provides for the neglected majority. But when Myla launched in 2001, the majority was already well cared for by Ann Summers: Gold's stores brilliantly service the mainstream, offering silly, boldly hued vibrators, tarty maid's outfits, kits for hen nights (bachelorette parties), and lewd lubes with names like Banana Dick Lick. Semler and Hampson were never interested in competing for Ann Summers' customers, who are unlikely to consider spending more than the $60 the store charges for Rampant Rabbit Deluxe. Instead they were after every retailer's favorite minority: fashionable women with money to burn.

If Ann Summers has perfected the jabbering, mass-produced feel of a chain store, Myla's two London shops (located in the toniest neighborhoods) exude the hushed posh minimalism of an exclusive Madison Avenue boutique. The store I visited in Notting Hill was clean, contemporary and track-lit, with brushed-steel hangers for Myla's range of lingerie made only of silk, satin or lace. (My by Myla, sort of like Marc by Marc Jacobs, does use cotton.) Four white square pedestals along the right-hand wall displayed Myla's four vibrators: Mojo, Pebble, Steel and Bone. Only four sex toys, but, as Semler told me, commissioning them from well-known British artists and designers was "absolutely pivotal to the business. Sex toys were the most stunning failing of the sex industry in terms of catering to our upmarket, design-conscious customer. Billions are sold around the world but they are all of them, without exception, absolutely hideous."

And Myla's vibrating creations are lovely. Bone, made of black resin, is the most phallic, but it still manages to look like sculpture; Pebble, which comes in slate, ivory or sand, brings to mind a Zen rock garden. They are also stunningly expensive. Bone, the most costly, retails for $360; Mojo, the cheapest (and also the weirdest -- it looks like a vibrating silicone nipple), will set you back $125. But that seems to be the point. Semler and Hampson have made vibrators palatable to their customers by making them baubles only the elite can afford. It's been a very successful strategy: In just three years Myla has reached $5.5 million a year in sales, making it an instant rival to the much more well-established Agent Provocateur. Like Myla, Agent Provocateur sells tie-ups, crotchless panties, and nipple tassels; unlike Myla, Agent Provocateur has the more predictable feel of a bordello or boudoir, and it does not offer anything with batteries.

It is also unlikely that Myla would have enjoyed its current success without Selfridges' patronage. As Semler put it, "It's almost impossible to underestimate the credibility and acceptability we gained from working with Selfridges, who were incredibly brave to take us on. No one had ever sold sex toys at an upmarket department store before."

Selfridges, for its bravery, got the kind of publicity only sex can buy, and it even featured Bone in its holiday window display. Liberty's, "the most old-fashioned department store in London," according to Semler, soon followed suit. That Christmas Liberty sold more Bones than any other single product.

I visited Myla's concession in Selfridges, and there they were: Bone, Pebble, Steel and Mojo, posed and ready to rumble. Standing in a massive department store the size of a London city block, buffeted by Saturday afternoon foot traffic while fingering vibrators in the most public of public places, I knew I was finally seeing something almost unimaginable in the U.S. -- even in New York. It is one thing to go to Toys in Babeland in New York, or Good Vibrations in San Francisco; it would be another to pick up a $400 vibrator at Saks.

Gold, in our e-mail exchange, said she "could eventually imagine launching in the U.S.," adding, "though I do think that the U.S. is more conservative." Semler, at Myla, was more direct. Why couldn't Neiman Marcus, which now carries Myla's lingerie, even consider carrying the sex toys? "Because you've got a whole bunch of religious fundamentalists in the U.S.! That's basically why." Semler did feel that eventually someone would do what Myla has done, particularly if an American department store like Selfridges took the plunge and lent the brand respectability. But it is hard to imagine this happening without protests, controversy, Fox News outrage, and boycotts that would make any major department store dildo-shy.

Not-so-luxurious vibrators, of course, are available right now at WalMart. As the historian Rachel Maines pointed out when I spoke with her, "Even in Texas (where a PTA mom was recently arrested in a "sting" operation for selling phallic sex toys) you can sell a vibrator at Rite-Aid as long as you don't say what it's for! The most popular masturbatory device in this country is the Hitachi Magic Wand." Maines' book, "The Technology of Orgasm," is a history of the vibrator, and it describes a time when electro-mechanical "pelvic massagers" were used by doctors in their offices to treat hysteria of the womb. In the 1880s American doctors actually used laborious steam-powered devices to bring their orgasm-starved patients to climax, but as soon as the first electro-mechanical vibrator was invented (by a Brit, incidentally) it caught on like wildfire, and eventually you could order one for yourself from the Sears and Roebuck catalog. Much like the "massagers" available in every drugstore in the U.S. today, these devices were camouflaged by medical rectitude, and it wasn't until the 1920s, when erotic films began depicting women putting them to use without a doctor in sight, that they stopped being advertised in respectable magazines.

This legacy lingers. It is still OK to sell "massagers" but not vibrators; it is still OK to sell orgasm aids as long as they don't look like penises and can be passed off as something else. Cherisse Davidson, the spokeswoman for Slightest Touch, a device that uses TENS technology to send signals of a "very specific frequency" to a woman's "pelvic region," sounded very American, compared to Semler and Gold, as she earnestly expressed a desire to "help couples" and described Slightest Touch as "so important for women." God forbid she should say it just feels good. (Davidson, bravely based in Dallas, also mentioned the religious right as an impediment to sales there -- S.T. has sold only about 20 units in Texas to "friends" while it has already sold hundreds overseas -- but quickly called back, nervously clarifying that her company had "no problem" with the religious right and in fact "looks forward to working with them." I wish her luck.) As long as Americans speak of sex aids in terms of dysfunction and disease, it seems, and not in terms of orgasm for the fun of it, American's puritan moral minority is not offended and all is well.

Shares