We seldom pause to ask ourselves the question "What is a film still?" So if I answer that it is a gesture of erotic possibility, bear with me a moment, and please trust that I am not just pushing a square object into a round hole. Nor finding one more way of asserting that everything comes down to sexuality. It does, but I recognize how unwholesome that idea can sound in America. So let me say, instead, that I am describing an incident of censorship. Or self-denial. I am addressing a dire act of closure that took place a few days ago in New York when the leadership of the Museum of Modern Art effectively closed its film stills collection.

What has that got to do with you, or us? New York must surely expect hard times (with the rest of us), and the Museum of Modern Art is torn between rebuilding, moving some departments and putting others on hold. All true. But the museum's latest decision does not really fit within a pattern of temporary adjustments. MOMA had once reckoned that it would have to move the stills to rural Pennsylvania for a while. Now, it seems prepared to suppress its own collection (and its own history in gathering, restoring and guarding the precious stills).

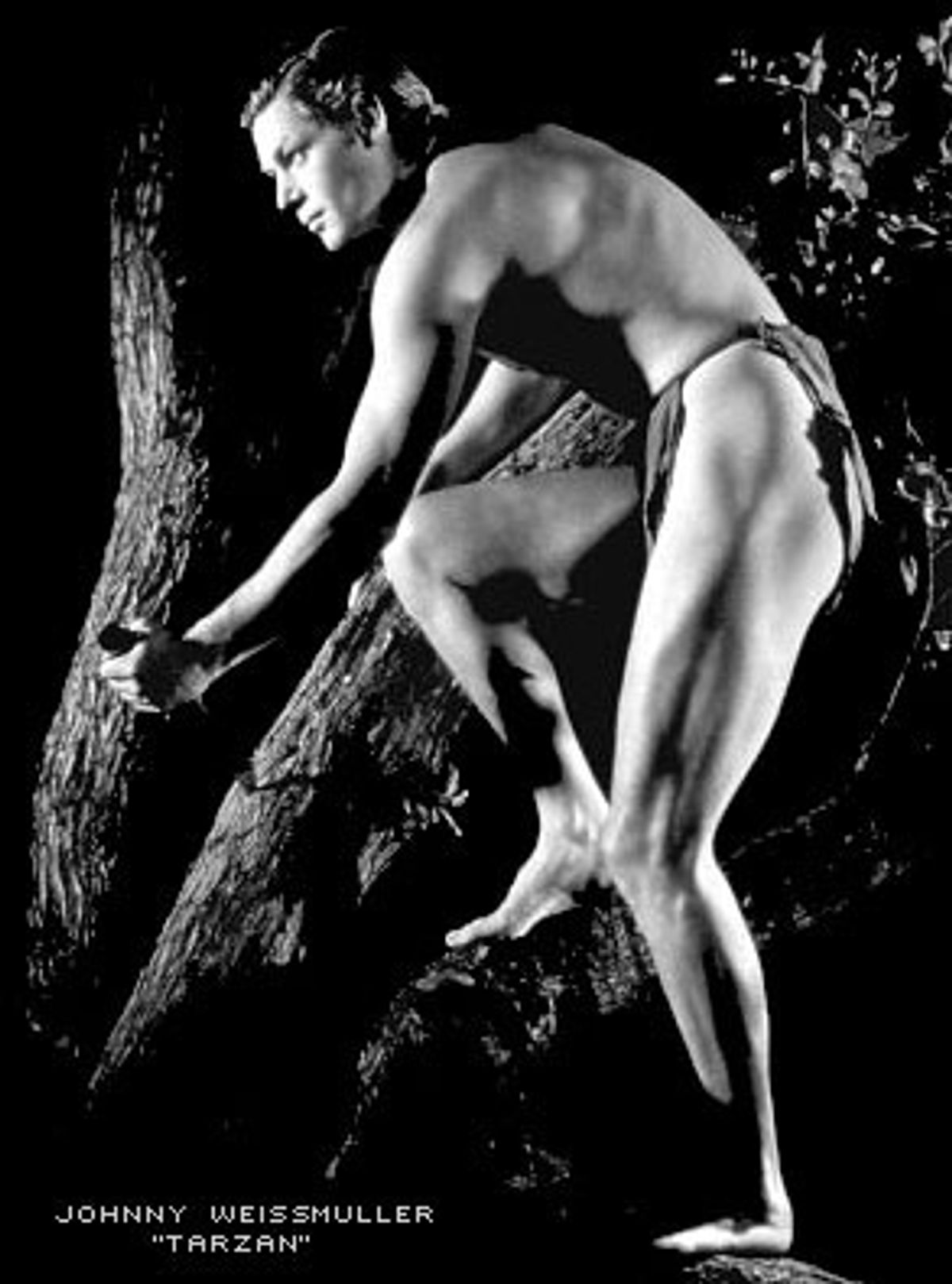

For while we like to imagine all the ways in which we have surpassed 1895 (the most available year for locating the start of moving pictures), it is remarkable how important that archaic thing, the still, remains. Yes, in theory, this is an age in which a film clip (a brief spurt of movie itself) can represent and market the motion picture. But in practice, as much as in 1900, 1930 or 1970, the film still is our invitation to the movie. Stills are the backbone of the ads and posters we see. They remain the essential means of illustration that newspapers and magazines employ. And in books about the movies, the still has never lost its role at filling a page with beauty, allure or glamour, or lost its power to suggest the visual quality of this or that movie.

But here's the intriguing unlikelihood in stills. Any young, smart person today is going to reach the obvious conclusion: that stills are nothing more or less than frames copied from the film strip itself. Don't we know that moving film is actually 24 still frames per second? So where else would the stills come from?

Well, sometimes in specialty magazines and learned publications, you do see that very thing -- what are called frame enlargements -- instants of the movie itself, the same image as seen in the dark. Yet, oddly, those frames do not often make effective stills. So many frames are actually blurred, or grainy, or not too easy to read. In theory, in an age of digital films those problems ought to be manageable: the image could be "shopped" clean; it could be dialed up so easily and quickly.

But film stills have not begun to do that yet. In fact, historically, the stills that have always been the basis for marketing movies were taken by still photographers, on set or on location, watching the actual cinematography and doing their best to imitate the tone and framing of the movie camera's composition. This may sound far-fetched as a process (and it still operates today). But note two things that spring from it: the way in which the stills were, initially, a kind of support for the film, a warm critical appreciation; and then consider the possible emergence of envy, or competition, an urge to make the stills more ravishing than the movie itself.

There was an age -- in the '30s and '40s -- when the taking of stills on movie sets was reckoned an art, and given to artists. Thus, there are photographers who did great work in the area who have honored places in the pantheon of photography: George Hurrell, John Engstead, Laszlo Willinger and many others. It's even the case that sometimes the fascinating art studies done in the studio affected the style of later pictures, and helped indicate the best ways to "see" a great star. Look through any album book of Hollywood in its golden age and you can quickly sense that creative interplay between the stills and the movies.

It bespeaks an intense interest in the look and feel of movies, and sadly that passion is past. Nearly anyone involved in the film business is now bewildered and dismayed by the indifference, the shabbiness, the absence of magic in those stills that major studios are using to market their product. It isn't just that geniuses are no longer employed. It's more that the job has lost prestige, and so the poor still photographer gets far less opportunity than was once the case.

In a way, that is the gravest admission in MOMA's decision to box up and store its fabulous collection of well over 4 million prints, preserved and cataloged, one of the treasuries of film scholarship and a resource used regularly by newspapers, television programs, magazines and books. No, it is not the only collection in existence, but it is truly one of the best.

As I said above, MOMA's decision is part of some very complex problems faced by that institution. But I think there is a profound problem that underlies all the practicalities: Movies are fading because they are not as visually urgent, alive and sexy as they were. We are not turned on by looking as we once were. And so stills that once felt like eroticized paper to some of us -- a sheen like shining skin -- are beginning to be relics. That is the larger tragedy, and the graver issue. But surely somewhere on earth -- or in Manhattan -- there is a home for these astonishing imprints of a great American moment.

Shares