CATALOGUE OF OBSOLETE ENTERTAINMENTS

GAME: Frogger

Format: Coin-Op Arcade Machine

Manufacturer: Konami

Year 1981

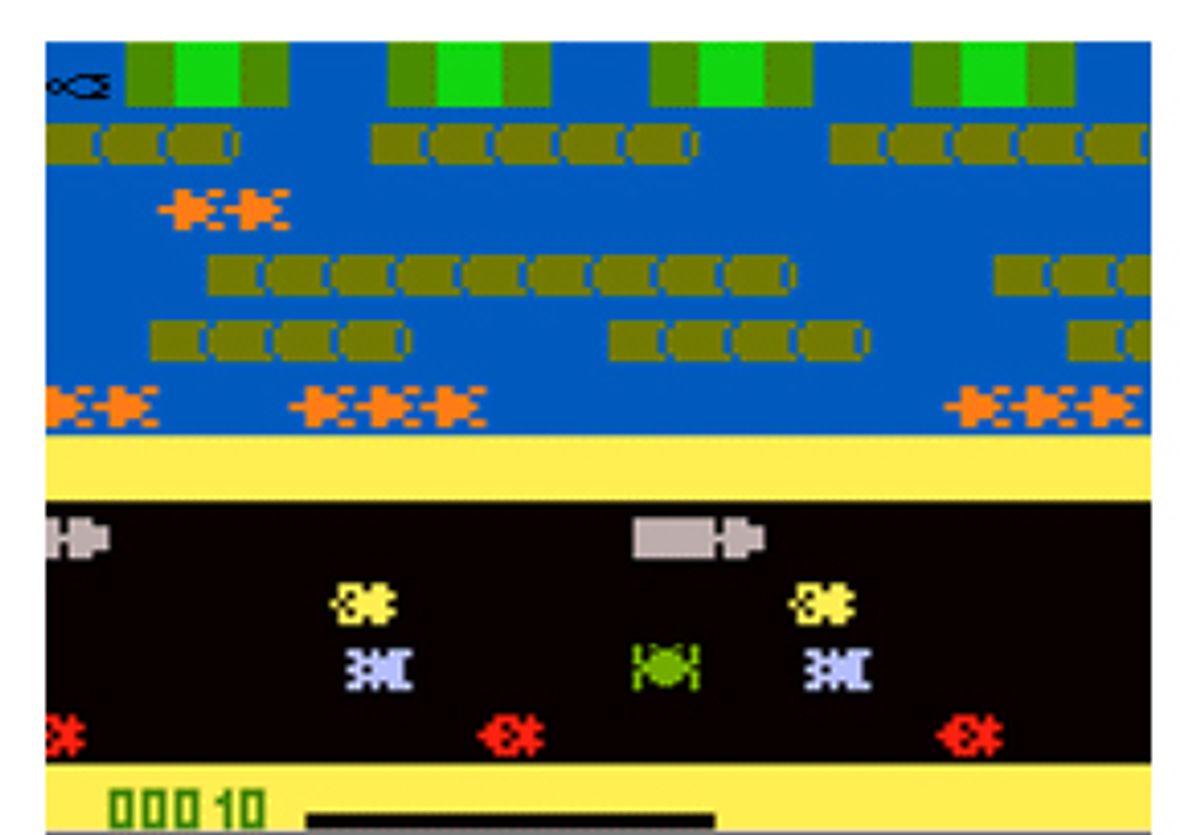

In "Frogger," you must try to get your frog safely across a road, median strip and river while dodging various dangers, into a frog haven on the top of the screen. When you fill up all five frog havens, they empty out, you start over, and the game gets markedly more difficult, with more dangers introduced. That is all.

Everyone loves "Frogger." Boys and girls, women and men, rich and poor, high and low. Who doesn't love "Frogger"? It draws its power from our shared memories of powerlessness. Wherever we are now, at one time or another we have all felt the poor frog's anxiety in the face of the world's intransigence, its blind and callous disregard for our happiness or well-being. We are not killing anything in "Frogger," except the occasional fly. It is all we can do to stay alive, avoid the fast cars, snakes, gators and weasels long enough to get a lady frog and make it to the top of the screen for our moment of rest. More than anything else, we'd love to stay in that Frog Haven forever, existing in a state of amphibian bliss -- but we are forcibly dislodged, and have to repeat the whole ordeal. Most of our antagonists do not even know we exist. They are not "after" us. We are not a target. We are just in the way.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

CATALOGUE OF OBSOLETE ENTERTAINMENTS

GAME: DOUBLE DRAGON

Format: Coin-Op Arcade Machine

Manufacturer: Taito

Year: 1987

Technically, "Double Dragon" lies outside the chronological confines of the "Catalogue" -- yet it was the author's personal point of departure from the world of video games, and showcases as well as any game the features and trends that mark the end of the Classical period.

With his blond high-piled hair, the avatar we are asked to play in "Double Dragon" resembles no one so much as William Zabka of "Karate Kid" and "Back to School" fame. Write it off to idiosyncrasy, but the notion that this ür-bully is supposed to be both the hero of the story and our on-screen representative strikes the author as preposterous, all past identification with "Donkey Kong" and "Pac-Man" ghosts aside.

More important -- and this speaks to the central problem with "Double Dragon" -- are the issues of surface versus structure, and inclusion versus exclusion. "Double Dragon" is the first major step down the road to a high-gloss realism that masks a shift from what Marshall McLuhan would call a "cool" medium to a "hot" one: "Any hot medium allows of less participation than a cool one ... the hot form excludes, and the cool one includes." Strip away this realism and the game boils down to beating the hell out of people, a fair-enough fantasy pastime...

But in cool games ("Tempest," "Raiders of the Lost Ark," "Lucky Wander Boy"), graphic minimalism goes hand-in-hand with the absorptive World Unto Itself quality that makes these games special, and indeed, a measure of this quality extends to all the Classic games, however basic in conception. When we play these games, the sketchy visual detail forces us to fill in the blanks, and in so doing we bind ourselves to the game world. Even more, we participate in its creation, we are a linchpin, a cocreator, crucial to the existence of the game world as it is meant to be experienced. Without our participation the Classic game is nothing, it devolves into exactly what the gloss-junky detractors see -- and they see it precisely because they refuse to put forth the mental effort required to round out the vision.

They prefer games like "Double Dragon," games that do all the work, premasticating the images, chopping them fine -- but in allowing this to be done for them, they go from being to watching, as the degree of detail starts to make identification with the character impossible. In his McLuhan-inspired book "Understanding Comics," comic artist and theorist Scott McCloud makes a deceptively simple observation: "The more cartoony a face is ... the more people it could be said to describe."

In "Double Dragon," I cannot be the ass-kicking Zabka; he has big biceps, and I do not; he wears a sleeveless blue track suit, and I will not. I am left out, and I feel left out enough as it is, thanks.

A Pac-Man, however, is just a mouth.

I have a mouth. You have a mouth. We all have a mouth.

And the world of "Double Dragon" is a world of car ads and wanted posters and brick buildings, not the iconic idea of a building we see in "Donkey Kong," but recognizable individuated buildings. The Classic games were Classic because, like classical music or architecture, they strove to give life and weight to ideals of order and proportion, to provide a vision of timelessness. In "Double Dragon," we can see the cracks in the brick, the mold growing on the drainage pipes, the unmistakable deterioration of the world we live in. We are thrust rudely back into time. When I put a quarter into an arcade machine or call up an emulated game on my computer, I do it to escape the world that is a slave to the time that makes things fall apart. I have never played these games to occupy my world.

Shares