A businessman drops his newspaper. Beneath him and closing fast, the outstretched flame of the Statue of Liberty looks close enough to scorch the paint off the airplane. Across the aisle, a passenger watches breathlessly as the twin towers of Manhattan's World Trade Center loom ahead. She can make out the figures of people on its rooftop observation deck. She is looking up, not down, at them.

A cut from a screenplay? Maybe, but those were the opening lines from a short article I wrote in 1996. What I described was a unique and unforgettable procedure that certain small airliners -- turboprops like the 15 and 19-seaters I once piloted -- used to follow when heading out of the triple-cluster airspace surrounding New York City. It was, probably, the single greatest flying experience of my life -- a ride along the VFR (Visual Flight Rules) "corridor" contouring the western edge of Manhattan along the Hudson River.

The corridor is a low-altitude trough of unrestricted airspace through which small aircraft can transit the metro area. Although thousands of private pilots have flown it in light planes, most commercial pilots aren't aware that we could do it too, albeit slightly higher and under the watch of ATC. Those aboard were treated to one of the most spectacular views in all of aviation, a rooftop-level panorama of the avenues, bridges, and skyscrapers of New York. As a line captain based in the Northeast in the early 1990s, the opportunity to fly this route was an enduring highlight of my job.

The patterns at La Guardia and Kennedy airports didn't normally accommodate a corridor run, but the runway alignment at Newark made it an easy shot, so long as the weather was good and volume not too heavy. The run could be made either when arriving or departing; landing aircraft were sequenced southbound down the Hudson, with takeoffs sent northbound just beneath them. The view was equally magnificent in either direction. Altitudes were assigned by ATC and staggered to avoid conflict. Technically you weren't in the corridor proper, but just above it, which allowed you to work with ATC while staying clear of the Pipers and Cessnas. Larger planes and jets couldn't join the fun, as regulatory constraints keep them on the more standard instrument flight paths.

For arrivals, preparation began at least 30 miles away. Boston to Newark was a common trip at our airline, and somewhere around Westchester was a good place to get ready. Step 1 was a polite query to New York approach control. "Is Newark taking traffic down the river today?" Usually the answer was yes.

Descending slowly, the idea was to intercept the Hudson near the Tappan Zee Bridge. Proceeding south, approach would next give you clearance into the city's restricted airspace, the Class B, which on a map looks like an enormous, three-ringed wedding cake layered over the tops of Newark, La Guardia and Kennedy. In the distance you caught your first glimpse of the jagged Manhattan skyline, sitting out there, to borrow a Vonnegut line again, like a giant quartz porcupine.

Rather than crossing the river way up near the Tappan Zee, now and then you'd get clearance near the "Northport stacks," nickname for a power plant on the north shore of Long Island about 40 miles from Newark. There was a standard, unwritten procedure for a river run from here. Regulars knew it by heart, as did ATC, who would rattle it off in staccato: "Cleared in New York Class B south stanchion Throgs Neck tower cab Central Park Hudson."

A first-time crew would stare dazed at its microphone if it hadn't encountered this onslaught before, but we understood it fully: From Northport we'd make a beeline for the south stanchion of the Throgs Neck Bridge, the first suspension bridge you come to as you near the city (second is the Whitestone). Then we'd head directly to La Guardia, passing exactly -- and ATC demanded exactly -- above the control tower at 2,000 feet. Next you crossed the north end of Central Park, then banked left to pick up the river. All around, LaGuardia and Kennedy traffic filled the sky. With TCAS (Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System) on board you could probably light the cockpit by the glow of its targets. One morning, an Air France Concorde whizzed past our left wing, a thousand feet above, inciting applause from the cabin.

Either over the park or across the GW, depending which of the above was flown, you'd now be dropped to 1,500 feet, and that's when it got sensational, the tops of the skyscrapers nearly at wingtip level. Skimming a forest of glass and concrete we'd race southward down the Hudson, passengers pointing frantically, faces to the windows, trying to identify Gotham's landmarks -- the blue bleachers of Yankee Stadium, the campus at Columbia, the Art Deco spires of the Chrysler and Empire State Buildings. Manhattan from the air is like nowhere else on earth, the cityscape split into hundreds of sheer vertical canyons, alive with rivers of cars and yellow taxis.

You'd stay at 1,500 until reaching the Statue of Liberty, which stands in the mouth of the river just beyond the tip of Manhattan. Then you begin a descending right turn for the runway at Newark. Early mornings were the prettiest, and a pilot or two was known to click a few pictures. Nighttime too was dramatic, and once during a rooftop light show at the World Trade Center we found ourselves illuminated in somebody's carefully aimed beam of neon green, like a bomber in the Blitz caught in a London spotlight.

Frequency changes and traffic calls came quickly. In addition to several approach controllers, you'd be chatting with both La Guardia and Newark control towers. Maximum speed in a Class B is 250 knots, but it was best to keep it slower. My usual target speed was 200 knots, with flaps set and checklists completed early. I'd throw all the lights on back at the Tappan Zee or Northport.

On the ground at Newark, the people thanked you for the thrill and deplaned. A new batch of faces came aboard, and then it was time to do the whole thing over again, this time in reverse.

We'd dial up clearance and ask for the "Governors Island Route" -- this one even more thrilling than the inbound. It's named for the island -- and U.S. Coast Guard base -- in the harbor near the Statue of Liberty. Something of a misnomer, it's the statue, not Governors Island, that became your target as you lifted off from 22R and made an immediate turn over the water.

What came next was breathtaking enough to warrant a preflight briefing, so passengers could enjoy the scenery without being frightened half to death: You'd pass overhead the statue at an assigned height of only 1,100 feet, then start a northbound twist up the Hudson. Things happened fast; it could take fewer than 15 seconds to reach 1,100 feet. Rolling out, the World Trade Center stood ahead, the north tower's antenna reaching 1,742 feet above sea level, about a mile away.

From there it was the opposite of what we'd done for landing, only now we're 400 feet lower. We could follow the river past the GW or do the Central Park, tower cab, Throgs Neck thing backwards. The controllers would offer step-climbs, and once clear of the Class B we'd sometimes go all the way to 18,000 or higher, where the high-altitude hush was sudden and stark.

Maybe that sounds like a lot of work and some risky kicks, but for a competent crew it was no more risky than most standard procedures in a busy area. The city's tallest hazards were the 1,522-foot Empire State Building, and the World Trade Center, both of which, however imposingly they loomed, were a legal distance away. All the federal regs were adhered to, though admittedly it was comforting to remember that rulebook caveat provisioning, "Except when necessary for takeoff and landing ..." There was an illusion of playing it loose when banked 30 degrees over the pointed crown of the Statue of Liberty or humming past a skyscraper.

A passenger came up front once on his way out the door. "I thought I'd seen it all," he told us, and his credentials were lofty. He'd flown the Grand Canyon, hang-glided off a Hawaiian volcano and once rode a helicopter through the Andes. His tour of New York, he told us, was at least as much fun. In the age of the generic, get-me-there-quick airline experience, it was a sensational treat.

Not until recently did I learn corridor flying remains active and legal. Having chalked it up as yet another casualty of Sept. 11, I'm pleasantly surprised -- astonished is more like it -- to find out otherwise. "After the attacks everything was closed off," says Mike Wagner, acting air traffic manager at Newark's control tower. "Today we're pretty much back to normal."

Alas, unrelated revisions to air carrier rules since the 1990s mean that most regional aircraft now adhere to more stringent IFR routings, limiting corridor traffic to all but the smallest commuter and private craft.

Two years ago today, when Mohammed Atta and Marwan al-Shehi steered their hijacked jets into the twin towers, they essentially pulled off corridor runs. Atta, at the controls of American Flight 11, intercepted the Hudson up near the Tappan Zee, just as we did, and followed it downstream until the target was in bull's eye view. Al-Shehi swung United's 175 to the southwest, coming in over the harbor with the statue and Newark to his left.

I think about those takeoffs I used to make from Newark -- the Governor's Island departures -- and how, just after Lady Liberty practically impaled the airplane with her pointed copper flame, those two monoliths would be sitting there in front of you, above you, quickly growing larger in the windshield. Exciting as it was, and with safety just a tug of the wheel away, there was always something unsettling about it, and I'd feel a twinge of relief, the slightest slowing of pulse and heartbeat, at the completion of the turn upriver, away from the buildings.

Atta and al-Shehi never made that turn. They kept going, fully aware that their 767s, along with themselves and untold others, were about to disappear in a molten, pulverizing concussion of infamy. It's something I can barely fathom, yet just the same I was practically there.

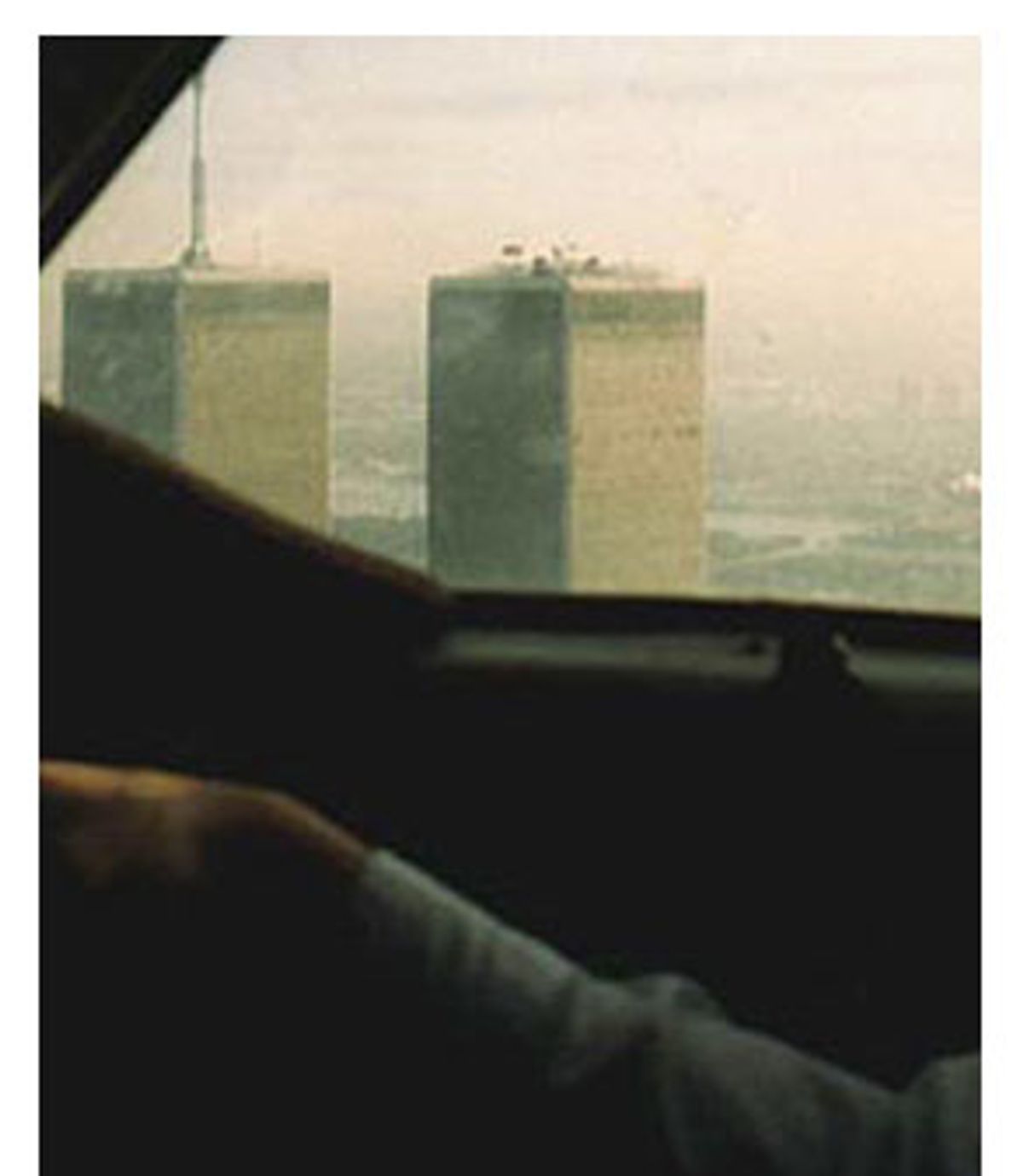

I snapped the attached, joltingly prescient photograph from the cockpit of a 19-seater in the early winter of 1994. Today, obviously, the vista from this point in space is a much different one, pilots rolling wings-level to a vacant breadth of firmament. The history of the World Trade Center was a star-crossed one -- the towers, a product of civic and architectural arrogance, were never a beloved landmark for most New Yorkers. But the skyline seems distressingly sad, ordinary and disoriented without them.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Do you have questions for Salon's aviation expert? Send them to AskThePilot and look for answers in a future column.

Shares