To be perfectly honest, I'm tired of writing about the Air France crash -- be it in spite of, or because of, the fact there's so very little to go on. And you're probably tired of reading about it. Plenty more has been going on in the world of air travel, no? We have captains passing away in mid-flight; the 48th Paris Air Show -- commercial aviation's big biennial bash -- wrapping up at Le Bourget; important testimony in Congress over crew fatigue and the hiring practices of regional airlines.

But, if you'll allow me, I've some loose ends to tie up with respect to Air France. Before moving on to a few reader-submitted questions, one or two comments on how the media has handled things.

Coverage of Flight 447 has been more or less as expected, if a tad better and more restrained than usual. With a few glaring exceptions, naturally. Take, for example, the New York Post's June 4 massacre of a story on the doomed airplane's "horrifying final 14 minutes."

The plane, we are told, was "flying through terrifying black clouds." Shortly thereafter commenced "14 minutes of death," culminating in a "dive of death." Look, the Post is a tabloid, I know, but still. Stories like this get the basic facts right, but couch them in a context of hysterical language and caricature. If I were a fearful flier, this is the kind of writing that would keep me grounded forever.

And this "black clouds" business is something that other, more august outlets ran with as well. Yes, cumulonimbus storm clouds can be menacingly opaque. But black? I suppose this is accurate in a sense, seeing how the crash took place at night, but how could anybody, with the possible exception of the occupants of the airplane, have any idea what the sky looked like at the time of the incident? I mean, really.

Next we have a Reuters piece from Miguel Lo Bianco. He writes, "Pilots often slow down when entering stormy zones to avoid damaging the aircraft, but reducing speed too much can cause an aircraft's engines to stall."

The danger of flying too slowly is not an engine stall, but an aerodynamic stall -- that is, a loss of lift over the wings. This is a common media mistake. They hear "stall" and automatically think engines.

More curiously, the BBC also botched a story. Gary Duffy, from BBC News in São Paulo, Brazil, gave us the following:

"The plane disappeared at what would have been the most vulnerable stage of the flight. When flights leave Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paolo, they normally make their way overland, I presume for safety reasons, for the early stages of the flight, for as long as possible. They then turn over the north-eastern coast of Brazil out into the vast crossing over the Atlantic. So it was at that vulnerable stage that unfortunately the plane disappeared."

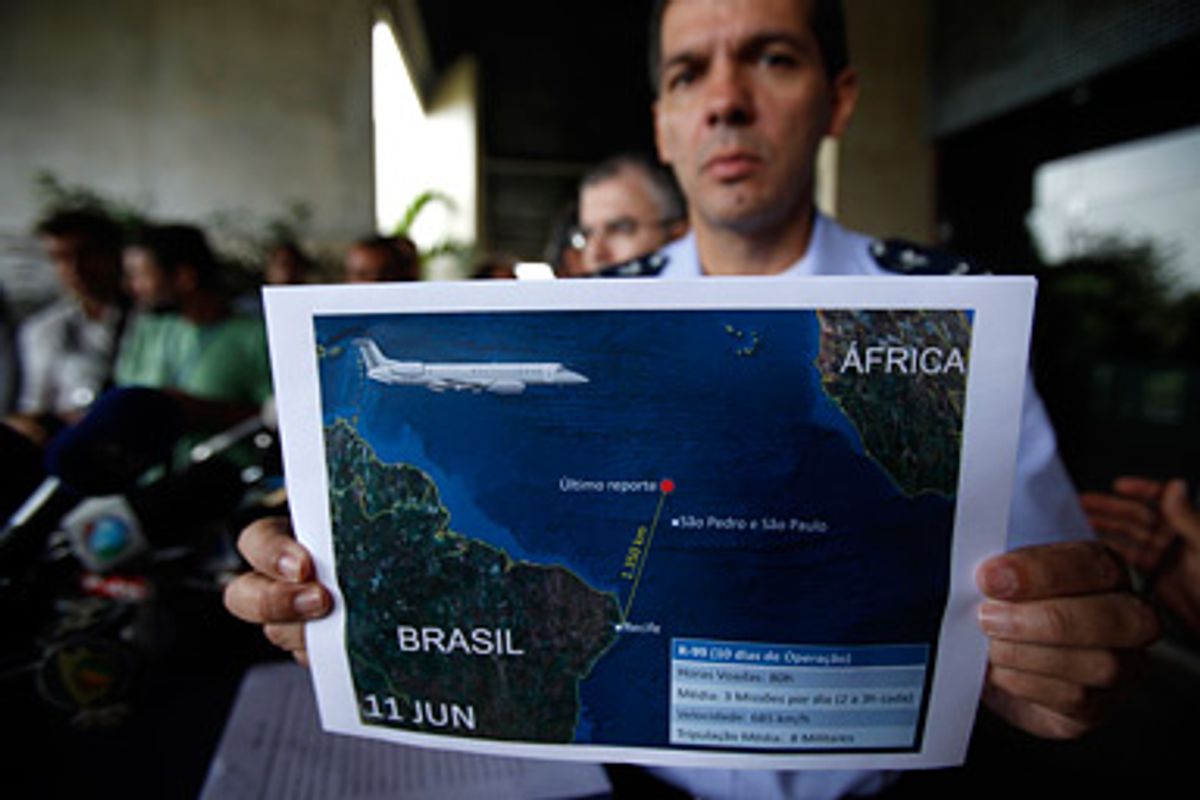

Well, not to nitpick, but that "vast crossing over the Atlantic" is actually one of the quicker oceanic crossings. From the corner of northeast Brazil to the next landing spot (either Dakar or Cape Verde), it is about 1,700 nautical miles. From there, the flight would have been very close to land for the duration of its journey. Seventeen hundred miles is a lot of water, but it pales in comparison to many Pacific crossings.

Neither is turning out over the ocean the "most vulnerable stage of the flight." Actually, it was one of the least vulnerable stages of the flight. Taking off and landing are statistically the most vulnerable stages of any flight.

But the big gaffe is the reporter's reasoning for why a Europe-bound plane would stay "overland" along the Brazilian coastline for so long. This has nothing to do with safety reasons. It's merely the shortest distance. Check the globe: A straight line from Rio de Janeiro to Paris takes you right along the eastern edge of Brazil, all the way up to the city of Recife. Without getting into a tedious discussion of ETOPS parameters, as they're called, an A330 is allowed to be as far as three hours' flying time from the nearest airport.

There is a similar, widespread misunderstanding about planes flying from the United States to Europe. These flights hug the American and Canadian coastlines, as far north as Newfoundland or Labrador, for hundreds of miles before crossing the open ocean. People often assume this is because they wish to remain close to land for as long as possible. It's not. Again, it's merely the shortest distance. Remember, the world is round, and planes fly "great-circle" routes -- the shortest distance between two points on a sphere -- which on a flat map often appear as great curving arcs. This is discussed in more detail here. Or create your own great circle routes, using one of my favorite online sites, the Great Circle Mapper.

The BBC also came up with this ridiculous hatchet job in response to last week's Continental Airlines incident in which the captain of a Brussels-to-Newark flight passed away during cruise.

There are those moments when you find yourself staring at the computer screen, taking in something so woefully wrong and distorted that you cannot get your arms around how to begin responding. This was one of those moments.

First and foremost, the comment by David Learmount, safety editor of Flight International magazine, is nothing if not outrageous. "That's what co-pilots are for," he says. "To stand in for the pilot in case of emergency."

It's possible this was taken out of context, but I have never in my life read a more absurd characterization of a first officer's job and responsibilities. As a first officer myself, my jaw nearly hit the floor when I read this.

Similarly we have this statement: "The main reason for having two pilots is that something like this occasionally happens."

That simply is not true. It is not even remotely true. The person who put this piece together clearly has no understanding of what airline pilots do, and didn't work particularly hard to find out. Could the BBC not have spoken to somebody with some expertise in the operational aspects of flying commercial airplanes?

Elsewhere, coverage of the Continental landing ran the gamut from acceptable to hysterical. Most commendable, of course, were those reporters who bothered to track down yours truly looking for a quote or two -- though I'm a tad confused as to why the New York Times chose to cite my name and my age, yet left out my writing credentials altogether. Go figure.

Both your column and news reports have spoken frequently of various "system status messages" that were automatically sent from the Air France A330 before its disappearance. Can you further explain this?

Messages regarding the health of on-board systems (engines, electronics, etc.) are periodically relayed via an on-board communications unit called ACARS, for "Aircraft Communications Addressing And Reporting System." This is mostly for data collection and trend monitoring, but it also allows ground personnel to be aware of any important faults, failures or developing problems.

Pilots also use ACARS for routine communications with dispatchers and mechanics, and occasionally with air traffic control. Info is typed in using a keypad and screen. The pilot hits a send button, and the message is transmitted over a VHF radio frequency, or via satellite when over the ocean.

Oh, and those times when the pilots announce baseball or football scores, those have been beamed up via ACARS as well.

If an aircraft is out of radar range, how regularly would the pilots keep in contact with air traffic control? It seems that 50 minutes, as was reportedly the case with Air France 447, is an awfully long period.

Fifty minutes between ATC reports isn't unusual. Crossing the oceans, flights make scheduled position reports to remote ATC facilities at designated points of longitude and latitude. These points can be very far apart -- 400 miles or more, at times. The reports are sent via ACARS or FMC, or manually by microphone (voice) over VHF, satellite or high-frequency radio channels.

Even far out over the ocean or other remote area, a flight must always be contactable. If an airplane is equipped with a satellite communications system, it remains more or less in instant and constant touch and can relay messages via ACARS or, if need be, by voice. Aircraft without a satellite system need to remain in VHF radio range in order to stay in unrestricted contact. Flying beyond VHF range, sans satellite, means the cumbersome and annoying use of high-frequency radio.

Why do airplanes rely on easily lost black boxes, as with the Air France plane or the 9/11 planes? Why not a continuous transmission of voice and data that is recorded remotely? That shouldn't be difficult in the age of GPS, satellite phones, Wi-Fi and so on.

I have been asked about this repeatedly in recent days. I posed the question to Christine Negroni, an aviation journalist and air safety specialist whose forthcoming book, "The Crash Detectives," examines air crash forensic techniques. Here is her response:

Mostly because it would require tremendous bandwidth in order to download so much information. Two hundred and fifty-six individual data streams are recorded by the flight data recorder [black box] of a modern jet, plus the recording of the conversations and other sounds in the cockpit.

Given how quickly communication and digital technology are evolving, it's feasible that soon it would be manageable to transmit this information using VHF radio frequencies when an airplane is in radio receiving range, but what about flights over remote areas or over water? Communicating this data would require data streaming via satellite, and that would be hugely expensive.

And where would all this information be stored? There are tens of thousands of commercial flights daily (all of which are uneventful, day after day). And even for that one crash in 2 million flights (the 2008 global hull loss rate), there's rarely a need for external recording. 'Easily lost boxes' is not an [accurate] characterization. It is a very rare occurrence when the boxes are not found.

Having said that, some stripped-down, essential parameters are already streamed from flights via ACARS when the situation warrants, as we've all been reading about with respect to the Air France crash.

How hard would it be to install a self-inflating lift balloon in one of these data recorders? Or why not make them buoyant, so they can float?

The recorders are not necessarily flung free from the rest of the wreckage. Chances are, they are tangled up in debris. And you'd need to concoct a way for the units to automatically disconnect from their various electronic inputs. But it certainly could be done. As could other things, many of them very simple, such as designing a black box able to emit a long-range GPS signal so they can find the damn thing, instead of relying solely on a sonar pinger.

Few in the press are saying anything about the possibility of a bomb. Certainly Flight 447 going down in the area of large thunderstorms suggests a proximate cause, but the question of a security-related incident cannot help raising itself in this day and age.

I agree, but the evidence doesn't suggest a bomb. The automated ACARS-generated messages are pretty explicit about a sequential series of instrument and flight-control faults, followed minutes later by a loss of cabin pressure. This, in or near apparently violent weather. On-board explosions blow holes in a plane, resulting in violent decompressions and/or structural failure, pretty much right away.

Also, just as important, nobody is taking credit for a bomb. Granted, when Libya blew up Pan Am 103, it did so anonymously, as did the Sikh extremists who blew up Air India 181 three years earlier. But today, most potential culprits have greatly different motives and would be seeking instant worldwide attention.

The Internet, of course, is crawling with conspiro-babble about this accident. This is the case with virtually all plane crashes nowadays.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Do you have questions for Salon's aviation expert? Contact Patrick Smith through his Web site and look for answers in a future column.

Shares