Next to vampires, no one hates the light as much as gamers. There's nothing worse than a big, bad glare blinding down on a computer screen. So when Ion Storm's crew moved into the penthouse of the Texas Commerce Building in 1998, they took one look through the wall-to-wall windows that afforded a panoramic view of Dallas and let out a gruesome, unanimous sigh.

The architects immediately set to work, installing stylish spoilers on top of the cubicles. But that proved hardly dark enough to suit the gamers' finicky tastes. Instead, the builders of anticipated first-person shooter Daikatana whipped out staple guns and nailed thick sheets of black felt over every cube in the office.

Now Ion Storm's 31 game developers don't just work in the shade, they work in the black. To get into their cubes, they part felt drapes like photographers entering miniature darkrooms. It was a fairly awesome and ironic sight as I wandered through the glass-domed gamers' haven last October. All I saw were rows of caves. And of these caves, Weasl's was the darkest.

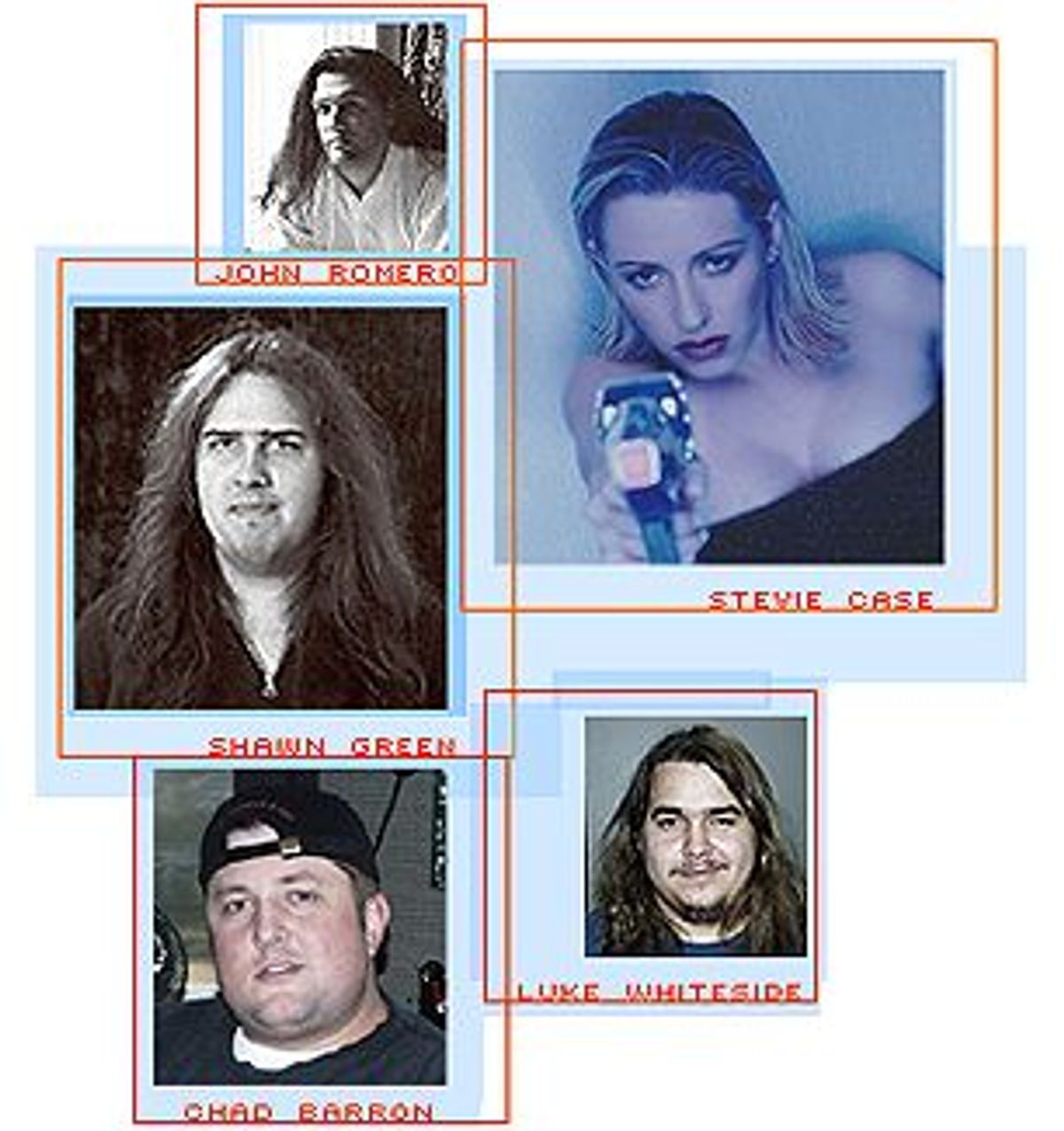

"I call myself a mushroom," Weasl told me as I crouched inside, "because I'm always working in the dark." With a couple extra layers of felt draping his cube, there's not even the slightest trace of light, let alone fresh air. But Weasl, a stocky, long-haired 20-year-old who resembles Meatloaf in the '70s, doesn't seem to mind. "Darkness is really helpful when you're trying to shut out outside influences," he explains, tweaking an animated pool of lava on his screen. "After you spend enough time in here, your personality adapts."

Luke "Weasl" Whiteside is the newest level designer to join the Daikatana team and, in a way, the most enigmatic. Since he came to the company just a few months before my visit, Weasl managed to miss out on Ion Storm's tempestuous back story. He's still so awed to be working here that sometimes he doesn't leave. Underneath his desk there's a pillow. On some nights, he hunkers down below his computer, munches some M&M's and goes to sleep. For Romero, who dreamed of populating a company with gamers as intense as himself, Weasl is as hardcore as it gets.

The only child of a single mother, Weasl got his nickname while growing up in a small town north of Seattle. "I always used to weasel out of things," he says. To get out of mowing the lawn, he would find the mower and siphon out all the gas. "I'd do anything for a little freedom," he says. Like Romero, Weasl never really fit in at school beyond computer class -- the one place he excelled. Weasl says he suffered from attention deficit disorder and bouts of depression and found it difficult to deal with the social and scholastic pressures. Instead, he drifted to the more imaginative world of role-playing games such as Dungeons and Dragons or Magic: The Gathering. "They let you be the person you aren't," he says.

When his favorite computer teacher left his high school, Weasl, then a freshman, dropped out. Just when he needed to, he discovered Quake. Weasl, never a big athlete, suddenly found a competitive, visceral arena where he could truly rule. He began spending all his time in online death matches and the burgeoning community of Quake message boards, newsgroups and chat. There, he met a group of friends and they started their own clan, 311, which would meet online to practice and compete. "It was fascinating to find all these people who thought the same way as me," Weasl explains.

Living with a friend who was becoming increasingly suicidal, he says he started itching for a way out. One night, Weasl, who had started designing his own levels of Quake, met another amateur mapper (gamespeak for a level designer) in an online chat room. The mapper lived in Dallas which, as Weasl well knew, was like Devil's Tower in "Close Encounters" -- the Mecca, home to Quake's designer, John Romero, and his new company, Ion Storm, plus a lot of other gaming companies. When Weasl gushed over the Dallas scene, the mapper told him he could come down and crash at his place. So last summer Weasl withdrew the $200 savings he had earned working at Taco Bell, packed up his computer, and got on a Greyhound bus headed south.

Once situated, he got down to work: mapping out his own level for a popular new shooter called Half-Life. He finished two weeks later at 5 a.m. Weary and with nothing to lose, Weasl e-mailed the level blindly to his hero, John Romero. As he crawled into bed, he hardly expected a response; after all, it was like sending a student film to Quentin Tarantino and hoping for a call. But when he woke up at about 6 p.m., not only had Romero replied, he wanted to take Weasl out to dinner. That night.

Hours later, Weasl was cruising shotgun in Romero's yellow Hummer. The two hit it off, talking endlessly about their favorite games and levels. A few days later, Weasl called his best friend back in Washington.

"I was like, 'Guess where I am, dude, Dallas!'" Weasl enthusiastically recalls. "My friend was like, 'Oh that's cool. What are you doing down there?' I said, 'Working at Ion Storm.' Then I could hear this silence at the other end," Weasl continues, cracking a smile, "and a couple seconds later my friend's like, 'What?'" Weasl shakes his head disbelievingly, apparently still struck by his awesome twist of fate -- the fact that he's actually here working with Romero. That he's no longer alone.

When I returned to Ion Storm in November, Daikatana crunch mode had turned vicious. Though the monsters, levels, sound and art were nearing completion, there was a formidable task ahead: burning through the remaining 500 bugs in time for a Christmas 1999 release. To attempt this (unsuccessfully as it turns out), Romero had upped the team's core hours to include weekends; the staff was elbowing for bed space in the lounge.

The death schedule was claiming victims. Mike Breslin, the company's affable vice president, had been stricken with the flu after a whirlwind marketing tour of the country. The virus had been making its way around the office, taking down a few other team members along the way. Most noticeably absent is Stevie "Killcreek" Case, Daikatana's accomplished level designer and only femme fatale. When Case had last come into the office, I'm told, her lips were blue from a kidney infection. A couple of guys down by the pool table suspected it had something to do with her crash diet. "Yeah," one added with an irrepressible grin, "she had to get ready for Playboy."

Case, 23, had been selected to appear in a six-page spread for an upcoming issue of the magazine. She caught Playboy's attention after its staff heard rumors about a bleached blond bombshell who had not only beaten the notorious Romero in an online death match, but got a job working on his hotly anticipated new game.

The legions of young men who populate the online gaming scene, of course, were intimately familiar with Case's story. As young men are wont, they eagerly drew their own conclusions about how this woman -- this chick -- landed herself in gamer's paradise.

"There's an assumption that the only way a woman could get on this team was because of her looks," Case told me during my last visit. "As long as I've been gamer, I felt I had something to prove."

Case grew up in Olathe, Kan., the daughter of a social worker and school teacher. As a competitive tomboy, she took to sports early on, earning the award for freshman athlete of the year at her high school. At the University of Kansas, she became a tomboy of a different sort, battling her guy friends in the online arena of Quake.

Though an A student, Case was already bored with her plans for law school. The more fun she had playing Quake, the quicker her plan faded away. During a trip to Dallas, Case managed to score a death match with Romero (who was known to challenge gamers who visited the office). Case lost, but just barely, and challenged him to a rematch. The next time around, Romero got clocked. As penance, he uploaded a Web shrine in Case's honor. Her last semester, Case played so much Quake, she failed to graduate.

Liberated from the law school path, Case returned to Dallas where she eventually found work as a beta tester at Ion Storm. Gradually, she felt herself shedding the Midwestern girl in denim pants and dirty-blond bob. "This was such a creative environment that I finally felt the freedom to be whomever I wanted to be," she says, "so I decided to reinvent myself." She stopped eating meat, went to the gym, lost 50 pounds, bleached her hair. By the time she had been promoted to a mapper on Daikatana, the new Case -- complete with breast implants, midriffs, leopard pants and a boyfriend, Romero -- was in the house.

Posing in Playboy, she says, is not only another step into self-confidence, it's her way to encourage more women to pursue their dreams, even if those dreams are told in computer games. "When people hear that I'm a gamer, they expect me to be unattractive and overweight," she says, "I'm trying to defy expectations."

It just goes to show, as corny as it sounds, sometimes when you play a game, you don't only win. You find yourself.

Brandishing my silver claw, I hear footsteps

It's a snowy, gray night in Plague Village, an ominous town in the heart of Daikatana's Norwegian episode. As Hiro Miyamoto, I have just jumped effortlessly off a cliff into the outskirts of a seemingly abandoned medieval town. When I look back up, soft layers of winter clouds sift quietly overhead. After the height of this cliff, I feel like I should be dead or, at the very least, limping.

Deep within the ominous strain of minor chords, I hear the icy crunch of footsteps approaching. Taking no chances, I brandish my silver claw in case the ones coming are werewolves. I jog cautiously around a nearby wooden shack that, upon closer inspection, is riddled with arrows. Crouching down, I do my best to hide but it's not working. The footsteps are getting louder. The forces against me are closing in.

For a moment, I'm reminded of the Ion Storm troops who have so adeptly instilled this fear in me -- and how, throughout their lives and careers, so many forces instilled the fear in them. As Daikatana finally nears release this spring (there are hints that the shooter really will hit shelves within weeks), they're more than ready for a little R&R. But, shortly enough, they'll be on to the next title. Crunch mode, after all, is a chance to live inside the game. But before they move on, they'll get the payback for their endless hours -- a chance to experience what mapper Larry Herring describes as "the ultimate rush:" knowing that others will soon inhabit the world they helped create.

It's no wonder my heart is pounding so convincingly. Leaping out from behind the shadows, I stand armed for battle. But, to my surprise, these aren't werewolves poised to end my dream. They're my faithful sidekicks, Superfly and Mikiko. How sublime it seems as the wind howls around us. In this most brutal of worlds, the gamers have given themselves friends.

Shares