"Get dating tips from the 'Sex and the City' divas!" "Believe in God's Diet!" "What women should know about erectile dysfunction."

Finding fluff on popular women's Web sites is like shooting fish in a barrel; it's so obvious that it's almost embarrassing to point it out. On these pillars of all things womanly, you'll find love compatibility calculators, diet plans, humiliating-moment confessionals, "secrets for sizzling summer sex!" and of course horoscopes, horoscopes, horoscopes. Other than a certain emphasis on resourcefulness, do-it-yourself-ism and pro-female positivity, there isn't much difference between the front page of iVillage and the cover of Family Circle, that of Women.com and Cosmopolitan (whoops, Cosmopolitan is now part of Women.com).

In the early days of the Web, fledgling sites like Women.com (then called Women's Wire), iVillage and Cybergrrl.com promised to provide alternatives to the shallow women's glossies on newsstands. In a medium then heavily dominated by geek testosterone, these women's sites shone as tiny post-feminist havens, modeling themselves after general interest magazines but with a heavy emphasis on community and more politicized content.

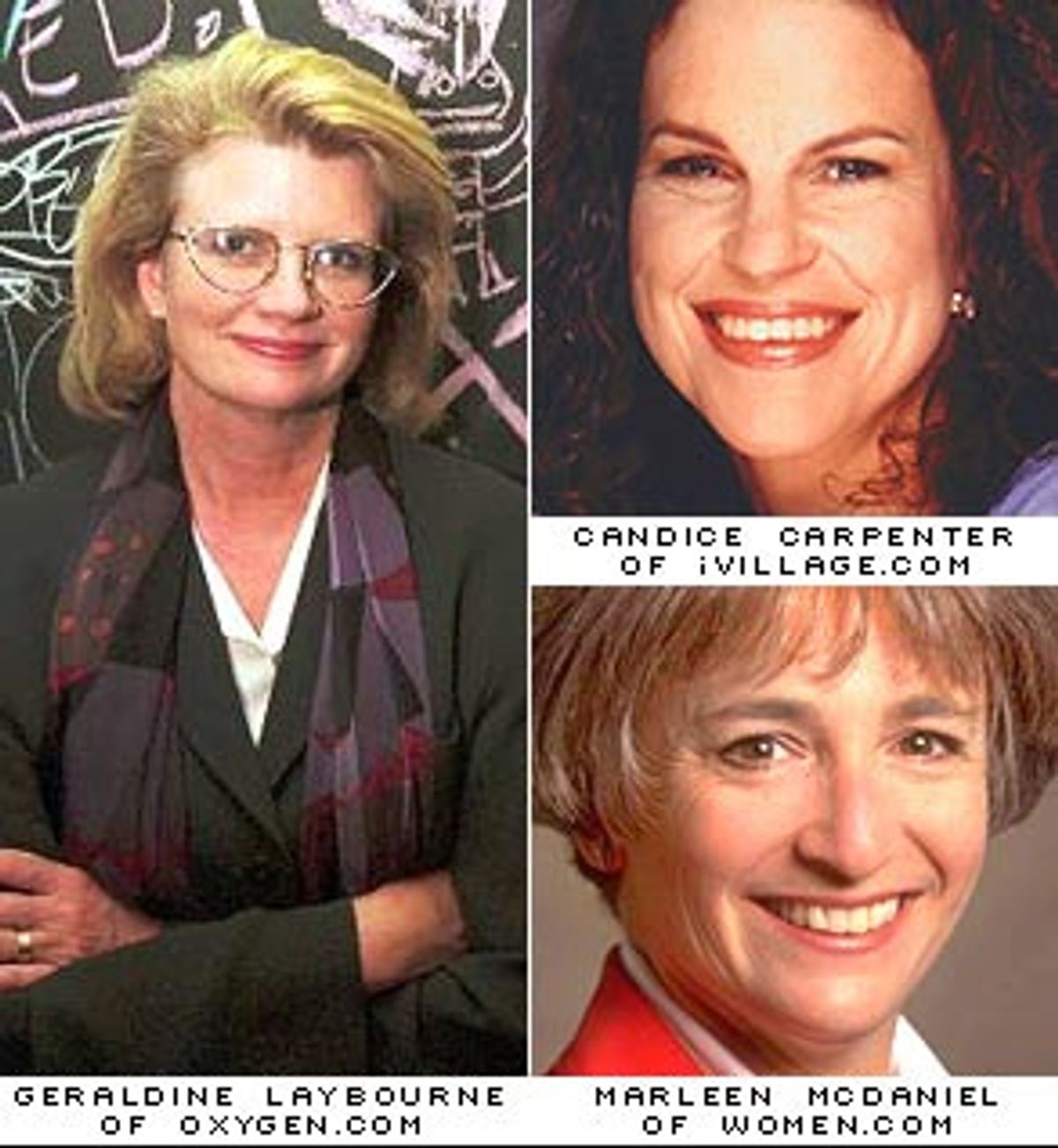

Now women make up 50.4 percent of the Web's population, according to a joint report released earlier this month by Jupiter Communications and Media Metrix. Great news for women -- no, Barbie, math isn't hard and computers aren't just for boys. But the news was anticlimactic for some: Five years into the evolution of the "Woman's Web," most of these original sites are suffering. Candice Carpenter, the most visible face of women's online publishing, has departed her seat as CEO of iVillage; Women.com has lost much of its original editorial team and is being kept aloft primarily because of a savvy merger with the Hearst women's magazine empire. A significant number of editors and Web producers of the much-trumpeted Oxygen.com have left, Cybergrrl is mostly forgotten and the young founders of the indie-zine network ChickClick.com have quietly left their own company. In the face of these departures and an increasing emphasis on the bottom line, the content on the sites is consequently becoming more and more mainstream.

Did you expect a feminist revolution online, empowering women to toss aside those astrology readings and turn off "Ally McBeal," in order to run for president on a platform of halting genital mutilation in Africa? Those who thought the Web would be more like Ms. than Mademoiselle -- believing that all women were itching for more intellectualism -- were probably deluded. (As the former editor of a now-defunct woman's zine, I include myself in that number.) As Francine Prose scathingly put it in the New York Times in February, "Only the most starry-eyed difference feminist could seriously have imagined that 'women's culture' would be any more noble, intelligent, high-minded or less blatantly meretricious than the 'male culture' peddled by Maxim magazine and Comedy Central's 'Man Show.'"

Half the Web may now consist of women, but what we are finding at the sites that are built with us in mind is often much of the same pabulum we'd get in People or Seventeen magazines. In fact, according to the most recent studies, women are going online in order to get People and Seventeen and that brand of 'women's culture' that so many feminists abhor. C'est la vie, c'est la rivolution. It makes one wonder: Now that women make up the majority online, do we even need "women's" sites?

When Geraldine Laybourne, formerly president of Nickelodeon and Disney/ABC Cable, launched Oxygen.com in 1998 amid a flurry of hype, she declared that she would be at the forefront of "a media revolution led by women and kids." She promised a full convergence network of Web sites and a cable channel focusing on the many aspects of women's lives, from shopping to news to health. As she told the New York Times, "The traditional media have missed the boat with modern women ... There is nothing that serves women the way ESPN serves men or Nickelodeon serves kids. We want to create a brand on both television and the Internet that brings humor and playfulness and a voice that makes a woman say, 'You really understand me.'"

One of Oxygen's first acts was to acquire a staff of veteran grrrl zinesters with lots of Web savvy. Besides hiring cred-heavy editors and writers from Bust magazine (founders of the "New Girl Order"), Laybourne also purchased indie webzines like Girls On Film and BreakUp Girl. Younger women were optimistic that the cable channel and Web sites would start developing content with an edgier, hipper sensibility than Women.com or iVillage. But two years later, Oxygen.com has let its acquisitions languish; and rather than developing any unique properties for its Web site, Oxygen.com now consists of a haphazard group of sites (including two dedicated to Oprah, one to "keeping it simple," another to "thinking like a girl"). Most of the sites appear to be half-empty or else mere place holders for Oxygen's cable TV shows. As for the cable channel: You're lucky if you've seen it, as it's only available in a handful of markets.

The exodus of a number of key Oxygen staffers was swift, including several show hosts and Web site producers. Last month, Oxygen.com's editor in chief, Sarah Bartlett, resigned; according to the Industry Standard, she was swiftly followed by Ellyn Spragins, V.P. of editorial; Deborah Stead, editor of Oxygen's literary site the Read; and three executive Web producers.

Why did Bartlett leave? Well, I can't know for sure, since I was unable to interview her, but I can take a guess. When she started the job, she told the Industry Standard she had come to Oxygen wanting to produce, as she put it, "really serious, hard-charging journalism ... and act as an advocate for women." But it's difficult to glean any hard-charging journalism from the sea of Oprah homages, fitness tips and relationship columns that you'll find on Oxygen.com.

Instead, staffers found a schizophrenic view of what content for women should be. As one former Oxygen staffer who requested anonymity explains it, the mix of zinesters and TV producers could never decide what the company was or who it was targeting. "Are you a women's property or a feminist women's property?" she posits as the main question facing new women's media companies. "Oxygen never knew whether it was a women's -- bring on the fashion and baby massage! -- or feminist -- bring on the Beijing plus five!"

Oxygen declined to comment on any of these issues. In fact, it is significant that no one wanted to speak to me for this story; no one from iVillage or Oxygen was willing to be interviewed about this subject. Heidi Swanson, founder of ChickClick, said she wanted to put her departure behind her; others who have left the various women's sites were unwilling to chat or difficult to locate. Those I did speak to requested anonymity -- because, most said, they still support the women's online publishing movement, respect their former co-workers and don't want to burn their bridges (even if they left disappointed). Some left for management reasons, others for ideological reasons; but clearly, it's an issue that many still feel strong about.

iVillage never had that problem. Of all the women's Web sites, it was the only one that was launched by a woman who wouldn't call herself a feminist. Instead, she was a hardened businesswoman who spoke of the women's communities on her sites as a commodity that needed to be "monetized." And, in turn, it was her ever-growing empire of baby clothing and pregnancy calendars, fad diets and personal shoppers that has proved to be the most popular (by a slim margin) women's Web site.

But with content sites no longer in investors' favor and losses growing exponentially higher, iVillage stock that once commanded $95.88 has plummeted down to around $7. Several executives left during the course of this year, culminating in late July when Carpenter was ejected from the company. Officially, she stepped down as CEO but remains as chairman of the board, although anonymous sources in unforgiving Silicon Alley stories say she was pushed out. Her position, ironically enough, is now being filled by a man. (iVillage didn't return repeated phone calls asking for comment.)

Women.com, which was always more edgy than iVillage, has been suffering from the market vagaries, too. What began in 1993 as a frank online discussion forum for savvy early-adopter women has become the place where you go to read Redbook, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping and a handful of other Hearst magazine Web sites. Although Women.com still has an editorial staff producing more woman-positive features (from on-the-floor coverage of the elections to advice for small-business owners), the company is being kept afloat by its more lightweight magazine partners. Even the smarter content has been diluted.

But the blame, perhaps, shouldn't be placed on Women.com's editors. There's a reason why Women.com these days seems to be so heavy on astrology and sex tips: It's because these are far and away the most popular features, despite Women.com's more thoughtful political and business coverage. "The reality is that the bread and butter of page views comes from sex and horoscopes -- it's the dirty little secret of any woman's site that that's where the traffic is," says a former Women.com editor. And to make matters worse, she says, "page views are put aside for beauty because that's where the advertisers were."

Although founders Ellen Pack and Marleen McDaniel are still holding strong at the top of Women.com, the site's original editorial team is mostly gone. Editor in chief Laurie Kretchmar departed this year; she's been replaced by Judy Coyne, who came from Glamour and New Woman and shrugs off concerns about the site's increasingly mainstream direction. "Magazines very often have to make a lot more choices about what they are going to offer; I've made some myself," Coyne says. "It's a great pleasure and a luxury to have an ability to do a larger variety of things. I don't think necessarily that there's been some big change of feminist philosophy of how to put [Women.com] together; but as it grows it encompasses a lot more things."

It was, say some former Women.com editors, an inevitable direction for the site to grow. "We might be the intellectual elite looking for a more broad mix, but you have to look at a bigger population," says one early Women.com editor who watched Women's Wire evolve over the years into a very different beast. "In the beginning the mission was to deliver smart intellectual stuff that makes women richer. And they still do it, but there's a lot more fluff around it."

But the problem, of course, is that it takes a lot of resources to produce content that spans everything from diet tips to election coverage; in short, such broad editorial goals are impossibly expensive. And women's sites are getting socked in the same places as other content sites struggling to get out of the red; they have to make hard choices about editorial direction, about business models, about staffing choices and marketing ploys. What's going to make the most money, draw the most traffic?

Most disappointing for the feminists who envisioned a generation of women choosing enlightenment over entertainment is the fact that women seem to prefer online horoscopes, sex tips, celebrities and parenting advice. Take the case of ChickClick, which began as a small umbrella network of independently produced grrrlish zines and now boasts 58 affiliates (a fact that in itself bespeaks some kind of revolution, if nothing other than a revolution of affluence on the part of young women). Among the alternative sites ChickClick publishes are ones like Scarleteen, a no-holds-barred sex advice site for teenage girls; Technodyke for young lesbians; and Women Count, a feminist political site that encourages women to vote.

Although the network boasts enough brash voices and alternative ideas to nourish a roomful of third-wavers, the two most popular sites on the network are, unsurprisingly, its most mainstream. There's eCrush, which lets girls send anonymous notes to their dream boys, and Mighty Big TV, an unapologetic daily synopsis of the trashiest TV on the planet. (Promisingly, a site called Disgruntled Housewife about grrrl homemaking is also very popular.)

That female readers are interested in celebrity sex and fluff was documented in the Jupiter/Media Metrix report earlier this month, which closely examined which sites women of all ages visited. The results? iBaby and Pampers.com, eStyle, Avon.com and OilOfOlay.com. There were no surprises among the most-visited women's community sites: iVillage topped out with 4 million monthly visitors, followed closely by the Women.com and Hearst sites OnHealth and ClubMom, with Oxygen.com coming in a few million behind.

And, painfully for these expensively constructed women's portals, some of the sites most popular with women are merely online versions of the old magazine rack standbys. Women.com staffers admit that it's the Hearst titles like Good Housekeeping and Redbook that have boosted traffic to respectable heights. And, even more disappointingly considering the plethora of smart teen zines online, the most popular sites for girls are CosmoGirl, TeenPeople and Seventeen.com.

Still, none of these sites is drawing that many women online. The most popular sites among women are the same ones most popular with men: Yahoo, AOL, Microsoft, Amazon.com and Excite. "Women seek ease of use and rely on the Web to make their lives more efficient and productive," crowed the report. In other words, they're using the Web for the same things men use it for: research, e-mail, shopping, searching. The fact that none of the women's sites -- which, with their offer-it-all approach, hoped to become the home page for all women online -- has managed to become the first-stop portal of the majority of the Web's women indicates that maybe women aren't heading online looking for women's content in the first place.

So, do we even need women's sites on the Web? Why Women.com, iVillage or Oxygen? There seems to be no real need for a catchall site for women: If women want fashion advice, they can go Fashion.net; if they want financial advice, there's CBSMarketwatch; for news, CNN.com; and for parenting wisdom, Babycenter.com. There's even Astrology.com for horoscopes. And if you really want women's fluff, why not just go to Cosmopolitan.com? There's a plethora of specialized sites for every need; the one-stop-shop model of the woman's general-interest print magazine seems irrelevant online. What were meccas for women in 1996 now seem somewhat like ghettos.

"The reason it never occurred to me to go to Women.com to read their news coverage is because I get my news every morning at the New York Times or CNN," says one former women's site producer who prefers anonymity. "I don't think that I ever felt like we were a part of a major women's revolution, specifically -- but more of a general revolution."

So what have these sites accomplished, then? In a word, community, and that is nothing to be sniffed at. Women have driven the strongest communities of the Web, from discussion boards at ChickClick to iVillage parenting support groups to "Are you a 10?" discussions on Women.com. The ladies like to chat; in fact, former iVillage CEO Carpenter recognized early that community was the strongest part of her site and threw her energies there, which is probably why the caliber of iVillage's editorial content suffered. "We don't view our mission as [providing] content in the traditional sense of offering information through articles," she told Upside in 1999.

"The Web has changed things for a lot of women -- I think a lot of the strongest online communities that I know of are run by, and are the ideas of, women," says the former women's site producer. "That's a huge, huge contribution to the Web."

But has there been a revolution in smart content for women? The short answer: There has, and there hasn't.

Maybe there was never a revolution to be had in the first place: Those looking for smart content should not, perhaps, be looking at general interest women's sites to find it -- just as men would never look to GQ or TheMan.com to stimulate their own intellectual hungers. It is probably too much to expect a site to offer both brilliantly incisive political theory and tasty fluff about Jennifer Lopez's outfits. Gender-specific content is always going to appeal to the trashiest, shallowest part of your gendered nature (and admit it, we all have that in us) -- and there's nothing wrong with that.

As Judith Coyne puts it, "It's a 'self-hating Jew' kind of thing to say that women have to turn against the kind of content that so many women like. A lot of women from different backgrounds and education levels are interested in certain kinds of content; I don't know why it's necessary to think that they are embarrassed by that."

But even if fluff sells, it's dangerous to be too dismissive of the Web's "feminist" revolution. Sites like Women.com and ChickClick are offering smarter content than your average grocery-store glossy -- stuff you never really saw before the Web, like daily election news discussing why older women participated in the Los Angeles demonstrations and reporting on the gay and lesbian caucus at the Democratic Convention. Not to mention frank sex education, homemaking tips for feminists and support groups for lesbians and breast cancer survivors.

Companies like Womensforum or ChickClick, which sell advertising across their networks of independent sites, encourage women of all ages to become their own publishers and then thrust that content (whether feminist rants, puppy food recipes or slavish musings on "Buffy the Vampire Slayer") in front of the eyes of millions. And the big commercial sites like Women.com, iVillage or Oxygen at least give encouragement to the many tiny alternative women's zines, like Women's eNews or Feminista, that won't ever register on Media Metrix. Every point of view is being expressed in the public eye, and that's a start. As the former Women.com editor puts it, "Anyone who understands the power of brand names knew that Good Housekeeping and Redbook would bring in millions of people we wouldn't see otherwise." The hope, she says, was that "if she came for Good Housekeeping she could find political coverage, too."

And although ChickClick will give Britney Spears heavy rotation, it also has a dedicated staff of reporters digging up stories about political issues, health advice and finance. "You always need to have a mix, and there is an entertainment element to the Web that we have to service," explains Rebecca Vesely, editorial director of ChickClick. "But there's also, from what we've seen, a real yearning for serious content. We just launched a 'work and money' section and both of those sites are two of our biggest draws now, and that's a big surprise."

No, we haven't overthrown the Cosmopolitan hegemony, and perhaps we never will. It seems that even the most brilliant women in the world love a little fluff -- and in a medium that trends dangerously toward the bite-size, that's what's easiest to consume. Besides, the more mainstream the medium, the more all-encompassing the content must be in order to turn a profit. It's no wonder that every women's site offers horoscopes -- women read them; I wouldn't be surprised if even Janet Reno occasionally checks in on her star sign.

The reason the early days of the Web seemed so promising of a feminist publishing revolution was that the choir was singing to itself: Young, well-educated women were the Web's earliest adopters, and while still sheltered from the rest of the world it was easy to imagine that everyone else was looking for the same thing. But these days, the Web is a mass medium -- and women's sites, just like other content sites, are competing with People, USA Today and CNN for the eyeballs of mainstream America. There are bottom lines to be met; and it's probably not the women's sites' fault that the best way to please shareholders is to pander to the lowest common denominator of celebrities and beauty tips.

After all, iVillage has succeeded in drawing millions of women; teen girls flock to TeenPeople; Women.com provides those horoscopes because the women demanded them. It is, perhaps, not fair to blame women's media for a revolution that didn't happen. Maybe there weren't more than a handful of women who really wanted it in the first place.

Shares