On July 17, Dallas-based video game company Ion Storm, founded in 1996 by legendary designers John Romero and Tom Hall, closed the doors to its controversial 54th floor perch. Eidos Interactive, the company that funded and now owned Ion, announced it would keep the Austin office open under the charge of Warren Spector, whose stellar game, Deus Ex, was the feather in Ion's cap, one of the biggest hits of 2000. Eidos said there would probably be a name change for the Austin branch. With that, the Ion Storm experience came to a quiet end.

I felt bittersweet sadness at the thought of those unmanned computers casting a lonely phosphor aura over Dallas. I had spent two incredible years in the employ of Ion Storm, writing for the games Daikatana, and briefly, Deus Ex. Unfortunately, there's been more trash-talk about Ion Storm than any other company in computer game history.

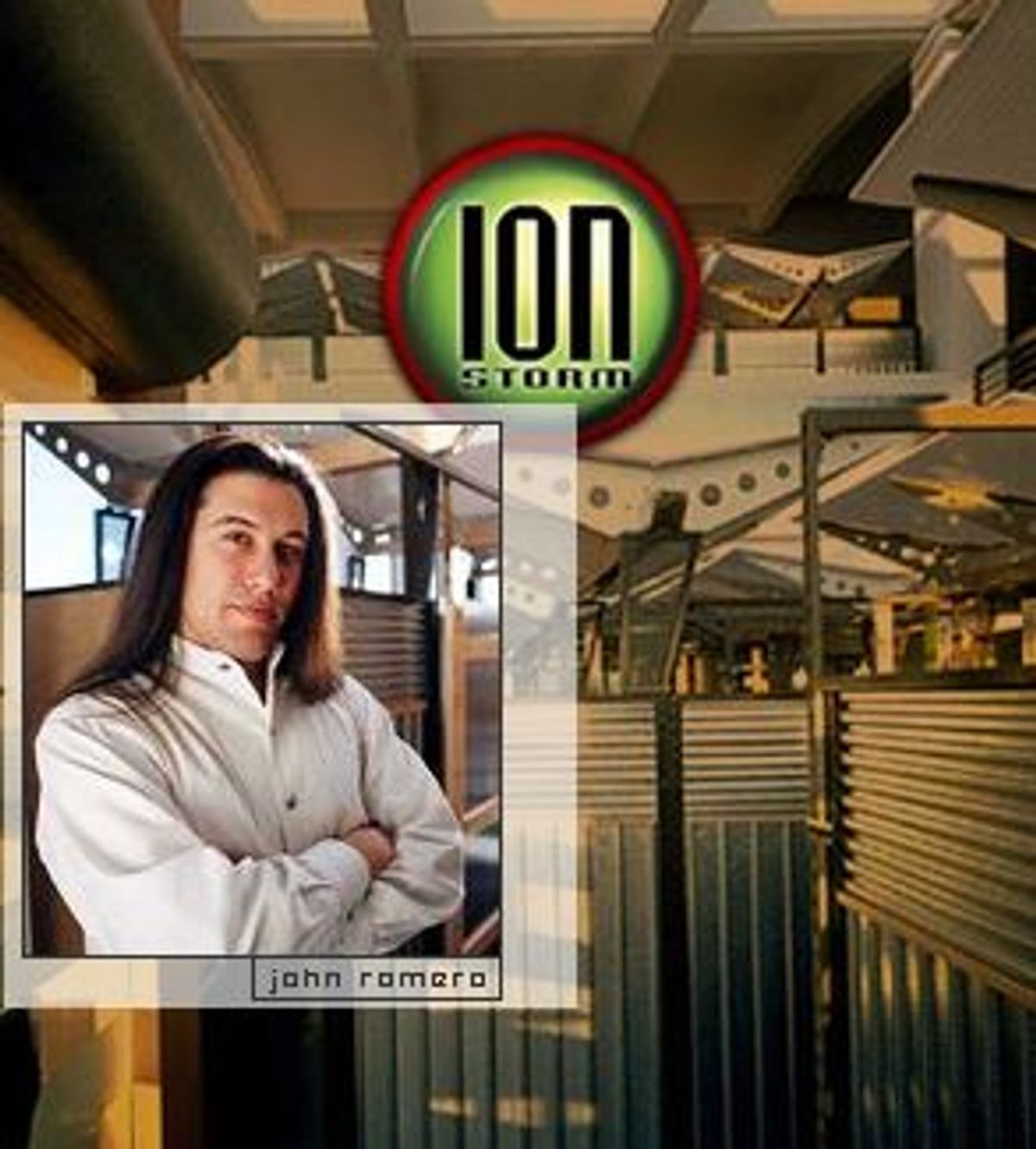

No place was more aptly named. John Romero was the focus of this industry love-hate affair: his popular games and extravagant lifestyle made him an icon in the industry. But with great success came great antipathy, not just for John, but also for many of his employees.

What started out as a video gamer's heaven turned into a public hell of walkouts, firings, lawsuits and litigation. Chat rooms and Web sites devoted daily commentary to analyzing, bemoaning or laughing at every move John made. He went from being one of the industry's most respected figures to one of its most pilloried. Few bothered to defend him or the company.

So I guess that leaves me, some six months after Ion Storm's demise, to carry the flag.

For three years, a group of unusual, talented individuals tried to push the envelope, to stretch computer gaming technology to the next level. So things didn't turn out the way everybody wanted. There were still good lessons to be learned. The assault on Ion was somewhat understandable given its unfulfilled promise, yet unreasonable because it was still a noble experiment. Amid the cyber-cackles from little boys who only wish they had the chance to work there, it's important for me to acknowledge what was actually great about being in that dimly lit tower.

I'll never regret my journey into the Ion Storm. And I won't soon forget the day when, as a student at UC Berkeley, I received a call from from my lifetime friend John Romero. He told me he had read one of my science fiction screenplays.

"Maybe you can do some writing on my new game," he suggested.

I left for Dallas a month later.

John and I grew up in the Sacramento suburb of Rocklin, sharing a love of Ray Harryhausen, Black Sabbath, National Lampoon, Harlan Ellison, Peanuts and William Castle. We drew perverse comics depicting the traumas of suburban conformity, subverting bland icons such as Richie Rich -- and often got busted in class.

By the 1980s, I was doing more serious comics and making bad short films while John hung out at the local computer store, played games and learned how to work on the new Apple computers. I had no aptitude or patience for scrolling numbers, so I stayed far away. Meanwhile, John created his own games. In Health and Safety class, he sat in front of me writing endless lines of code on sheets of yellow paper; behind him, I drew epic comics and wrote short stories. We both almost failed. John sold his first game when he was 16.

It was cool to see his work in the pages of computer magazines. He moved to England with his family, worked on military computers, then back to America. He cruised through various software companies before co-designing an updated version of the Castle Wolfenstein video game. With its gun-leading-the-way perspective, labyrinthine hallways and evil Nazis (with dogs), Wolfenstein solidified the "first person shooter" genre and became the most visceral action game of the day.

John's devilish sense of humor was all over Castle Wolfenstein, from the clever level design to the increasingly battered face of a player losing strength to the computer-generated insults whenever you tried to quit the game. John and the game's technical genius, John Carmack, soon formed their own company: id Software. With money in the bank and time on their side, id released the computer game that would revolt and revolutionize the industry: Doom.

Id's success became a worldwide phenomenon with Doom's sequel -- Quake. But the Romero-Carmack collaboration didn't last -- after the release of Quake, John Romero left id. The split generated endless commentary from gamers and was the subject of countless press reports. From my perspective it was obvious that John and id were going in different creative directions: Carmack's focus was on extreme technology, while Romero concentrated on game design.

After id, John brought together two of the industry's most original talents, Tom Hall and Warren Spector, to form their own company. Todd Porter also came onboard with his strategy game Dominion. John was the most high-profile gamer in the biz, so the team had no problem finding interested backers. Eidos Interactive, home of Lara Croft, put down the big startup cash.

Most stories about Ion usually start with the late-night ambiance of gamers destroying their pixel alter-egos in one form or another. The trash-talk is foul and funny, witty and mysogynist, homophobic and democratic, and unremittingly non-personal.

I can understand being horrified by the scene. I was at first. However, when somebody shouts out "Suck it down, cocksucker. Your ass is mine!" right before they splatter your player into bloody gibs, it's really little more than the geek equivalent of athletic taunting. Part of the gamer's code is to not take this personally.

Yes, there was a serious edge to the playing, the same earnestness you'd see in any sporting event. I found it interesting that people at Ion who probably never made it on a football team developed the same competitive standards with video games. Myself, I chose a delicate title, "Grumpy Bunny," for the nightly Quake Deathmatches. Since my co-workers had lofty, threatening names like "Master Destroyer" or "Lord Yog Sothoth," I figured that being fragged by "Grumpy Bunny" would be extra-humiliating.

Eventually I too found myself screaming obscenities as I chain-gunned my video opponents. But I was actually a shitty player. John Romero wouldn't even Deathmatch with me because I was so not hardcore.

So there I was, atop the 54th floor of the Chase Building, the tallest and most exclusive in Dallas, a glass and chrome Wonkaland (minus the scary Oompa-Loompas). Across the street below stood a red brick church, a small icon of faith in the midst of this corporate metropolis. Jets and airplanes coasted overhead, close enough to imagine a disaster movie scenario. The company's layout was a hi-tech wet dream: pool tables; arcade games; big-screen TV room; private theater; cozy leather couches; $1500 chairs; even a shower for unclean and dedicated employees. Each game team also had a cache of unlimited sodas and treats. No, it wasn't too bad.

Ion came in for constant attack because of its extravagant digs. The critique wasn't entirely offbase. Most people in the computer industry do their intense work under the cloak of dark rooms and lit screens. Enclosed by vast sheets of glass, Ion was more like an air aquarium, with shafts of hot Texas sun cutting into every nook and cranny. The various teams ended up covering their cubicles in black sheets. A warehouse far from downtown Dallas might have been more suitable, and certainly cheaper.

The first months of Ion Storm had all the excitement of any new relationship. Everybody was high on life (and from 4:20 breaks). I began to meet my co-workers. One salient aspect of the computer industry is the lack of social conventions -- and graces. Few people ever introduced themselves to me when I arrived, so I made a concentrated effort to shake hands and ask questions.

The artists were the easiest people to know, the ones I admired the most. Maybe because they're the grunts of the industry, painting pixels and rendering shapes, creative and controlled, and the ones who went home at a decent hour. I envied them their cool gig. 21 year-olds getting paid up to $50,000 a year to draw monsters. Wow.

The cliche that a company is only as good as its people is true, and Ion Storm had an amazing collection of employees: some wildly talented, some borderline geniuses, some major oddballs, and some total dicks. There were Christians, Mormons, Buddhists, a shitload of atheists, and only 2.5 women at any given moment; it was good to have them around. The median age was probably 25, and you could talk with anybody about Godzilla, Ayn Rand, Bill Hicks, Noam Chomsky, Phillip Glass, Jack Kirby, Barry Adamson, John Carpenter, Stephen Jay Gould, Yukio Mishima, the Illuminati, Douglas Adams, everything under the sub-cultural sun.

Cubes were decorated with erotic anime posters, the inevitable Star Wars toys and indecipherable Todd Mcfarlane figures. The films "Alien," "Aliens," "Blade Runner" and "Evil Dead II" were undoubtedly the most influential. Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger was hands-down the most imitated artist; no level design was complete without a shameless variation on his brilliant and disturbing bio-mechanic artwork. Japanese manga was the art-style of choice, though there were many overbulky superheroes. Music tastes ranged from A-Ha to Zappa. A John Williams soundtrack blared from one cube while Nine Inch Nails blasted from another. Yes, a true geek fantasy.

Despite the social misfit-ism, the game world is far more accessible and democratic than any other media industry. Designers, programmers and artists are in constant touch through the global network. Getting a dream job can be as simple as sending off a great Quake map to a bigwig -- as when Luke Whiteside was hired after sending John a sample of his work. One's skill or talent at design is self-evident without a Ph.D., or a capacity for tunneling through bureacracy. Ion's critics never bothered to acknowledge that John always searched out and encouraged new talent for his company. He never forgot his gaming grass-roots or the people that had helped him out. This was the creative environment that Ion fostered.

Then came the infamous ad.

Yes, the "John Romero Is Going To Make You His Bitch" ad for Daikatana in late 1997. Since game magazines are niche-oriented, the controversy was contained, but it still left a permanent scar on the perception of the company. I thought it was a funny idea to parody the prevalent trash-talk that Doom and Quake had set in motion, but not everyone agreed. The ad's lifespan was short.

Its main effect turned out to be focusing a new wave of trash talk -- this time from gamers aimed directly at Ion Storm. I found it fascinating to work on a project that the online game world obsessed about so intensely. To read daily gossip about events that were and weren't happening gave me a chance to observe the online media's ill-defined "objectivity."

It was almost like a drug to scan the gaming sites and see what nasty news was leaked or invented. I suppose it was one side-effect of the way the industry was so intimately and electronically connected to its fan base.

But the lines had been drawn. All eyes were now on the Storm and of course, Daikatana. To compound the growing pressure, the marketing machine put John Romero everywhere -- making him the poster child for both Ion and all first-person shooters. He made the list of Entertainment Weekly's 100 Most Important People in Entertainment; Time called him the "Quentin Tarantino of the game industry"; CNN did a piece on the Dallas office, where I felt a Warholian thrill seeing myself kick ass on Tekken 3 to a global audience.

Contrary to popular belief, John didn't care about the publicity; he saw it as a necessary evil. He certainly didn't act like a prima donna. We still ate Sonic cheeseburgers and watched Don Knotts movies at his stately home. John Romero is truly one of the least pretentious people you could meet, and I never saw him treat anyone as if he was the gaming world's "rock star." He made it a point to hang out with his fans, e-mail them and be approachable. He loved going to death-match tournaments and battling it out with his peers.

Personally, I got a kick out of seeing my school friend treated like a game god. John laughed it off. His generosity in starting a company and hiring talented people at excellent salaries (with benefits and potential shares) would rarely come into play during the gaming media's war with Ion.

But as Daikatana's release date continued to slip, working at Ion Storm became more and more like being a character in a minor soap opera being played out live in front of the game community. I thought some of the members acted like -- to use their own parlance -- whiny little bitches; they obviously saw themselves as the arbiters of Good Games Everywhere, much like the new breed of film geeks on Ain't It Cool News.

The immediacy of online raving and ranting encouraged a perpetual, streaming critique of Ion Storm. Flame Thrower and Bitch-X were the most nasty and vociferous gossips, running daily doses of rumor, innuendo and even fact. It's a typical media paradigm: put somebody on a pedestal and then kick it away. Their venom made the news irrelevant; the point was to bring down Ion. Everybody at work read these critics, argued or agreed (or perversely sent them the inside scoop), and the attacks didn't contribute to an optimistic environment.

I was disturbed by the hate and bitterness on the message boards. To me, there was an unmistakable jealousy on the part of his detractors. John had spent half his life making computer games, and he didn't have to prove anything with Daikatana. He just wanted to make a cool, original game. Not that he was innocent of a certain hubris, but he did nothing to warrant online thugs dragging his personal life into their stories. I realized how awful it could be in the public spotlight, how difficult to let negative words slide off your back. I don't think John or anybody ever expected this level of animosity.

John helped create a whole genre that literally changed the face of video games. He publicly advocated creators' rights, never met a game he didn't like, never talked ill of people or rival companies. He gave everybody the freedom to do what they were best at. Maybe John had too much trust in people; but this is not a bad thing. And there was definite online fan support for him and Ion. But the cyber-critics had their itchy trigger fingers on the mouse. Ion became the bad guy in the game of life.

The months stretched into two years, and development slowed due to the changing technology, not to mention warring factions of the team and management. I figured Daikatana could end up like "Titanic," the movie, or Titanic, the ship. Either we were going to take over the world or go down in flames.

There were already icebergs, seen and unseen, all around us. Expectations for the game were beyond high and climbing. An early hint manual was prepared as an ad supplement without the game actually being ready. Marketing moved faster than the team possibly could, causing more rumblings. Dark clouds circled the horizon.

Yet I had boyish confidence. This was a visionary approach to the genre, and if first person shooter games were to evolve, then Daikatana would be the next logical step. When John told me that story and dialogue would be integral to Daikatana, he stressed his desire to push the boundaries, to make the world emotionally immersive. He wanted the epic quality of the Final Fantasy games, that unique brand of anime science fantasy romanticism.

Basically, John wanted Daikatana to be like playing a movie. He realized that the shooter genre would have to move beyond "just blowing shit up," as he often put it. John laid out the basic storyline, that of Hiro Miyamoto (a homage to legendary Nintendo designer Shigeru Miyamoto) and his quest for the mythical Daikatana (awkward translation: Big-Sword) through the halls of disrupted time. Along with the de rigueur violent action, there would be personal drama, moral challenges, complex time-travel physics and a surprising revelation at the climax. This was certainly beyond the scope of Duke Nukem and Quake 2.

John went all out. Daikatana would have two sidekick characters, four different environments, over 30 weapons and monsters, and extensive cinematics between gameplay. John even wanted the Greek level to mimic animation master Ray Harryhausen's mythological style. Caught up in the storytelling possibilities, I envisioned the apocalyptic San Francisco as a psychedelic wasteland.

But I learned how valuable my ideas were when I excitedly approached a designer about making a psychedelic level in Haight/Ashbury.

"Yeah, man, sure, that's gay," was his arctic response.

I'd forgotten I was just a writer. The designers were in charge of the environments.

Despite all the negative drama, I was still happy. How could I not be? These were strange and wondrous days. Settled in my cozy steel cube, scented candles burning, shelves lined with GI Joes, a poster of Steve McQueen as Bullitt watching my back, Air's cool vibes playing from my speakers, getting paid to write for a visionary computer game -- dreams were coming true all around me. I was living a boy's adventure tale.

Those are my best memories of Ion Storm, those midnight hours of writing between bouts of Web-surfing, staring at the lit planes above or the twinkling carpet of Dallas below. My head was literally in the clouds. I loved the cathedral silence of the immense Chase building. I was a corporate voyeur, staring at empty offices and halls, walking alone under fluorescent lights, driving down the sterile tollway at 3 a.m., retinal Quake residue making the road an endless hall sans monsters as Delirium's gothic trance soundtracked my ride.

To me, Dallas was a bland, yet protean, city of the future, and Ion Storm a citadel of electronic creativity. On the edge of the 21st century, I tried to take nothing for granted.

Which is why the bitter complaints from some employees felt hollow. There were absolutely valid reasons to gripe about the direction Ion Storm was headed, but feeding that ambiance of defeat seemed, well, defeatist. Not that I didn't bitch. During cigarette breaks, I would join the others in condemning the rampaging egos and control-freaks. Still, I had faith that Daikatana and the company could rise above the bullshit. Look up "naive" in Webster's and see me wave.

My own turn at Daikatana controversy came in the form of Hiro's sidekick, Superfly Johnson. I originally named him Superfly Williams -- in honor of the classic blaxploitation film/soundtrack and Jim Kelly's character from "Enter The Dragon." Superfly was to be of French origin, his name taken from the few cultural documents left in the apocalyptic future. His character arc would be finding out his real identity at the end. Not too heady, but certainly not a stereotype. I tried to explain to the genuinely concerned designers that the name Superfly came from a great 1972 film and greater Curtis Mayfield soundtrack.

The very next day, one of the designers brought in the Lifestyle setion of the Dallas Morning News, featuring a front-page article on the cultural resurgence of blaxploitation films...and the 20th anniversary re-release of the Superfly soundtrack.

I was vindicated until the game's release: Superfly "Johnson" now ran around the levels and said, "Wassup?" He was awarded most stereotypical character in game history by a few gaming sites. I still defend Superfly's noble origin, and in an industry of jive-talkin', afro-wearin', pimped-out black video game characters (as in Tekken or Interstate 76), I don't think Daikatana can accept the award. I noted that most gamers had no problem with sexist female characters -- as in Duke Nukem, where the player is encouraged to splatter half-naked strippers.

After Daikatana, I moved gratefully into the cultural oasis of Austin to work on Warren Spector's Deus Ex. In terms of publicity and controversy, Ion Austin had it made. Far from Dallas, Spector's low-profile approach kept the game out of the cyber cross-fire. The team and office were smaller, and Deus Ex had a tighter deadline that kept everything in focus.

Meanwhile, the news from home base got worse. After my Austin transfer, nine core members of the Daikatana team walked out. A bigger conflagration came when the Dallas Observer ran a cover story called "Stormy Weather" about Ion's internal strife. Filled with fact and gossip, punctuated by leaked e-mails, the story brought the ownership woes to the public-at-large. No matter what I thought of the control freaks at work who were sinking the company, I thought it was sleazy and irresponsible to publish private e-mails, especially ones that revealed employee salaries. I fired off an angry missive telling the Observer that Ion was making video games, not hiding toxic waste.

Daikatana and Deus Ex were finally released in 2000. Predictably, Daikatana was slammed while Deus Ex received many awards. Both made money for Eidos, but the walk-outs, firings, lawsuits and general bad blood doomed Ion Storm. After the release of Anachronox, Eidos pulled the plug on Dallas. Game over.

Everybody who came to Ion Storm had their life changed one way or another. I made eternal friends, loved a wonderful woman, had fabulous adventures. The memories are vivid enough to hold in my hand, and I enjoy revisiting them. We'll especially remember Doug "Fresh" Myres, one of the genuine good guys in the industry, who left our world earlier this year. The outpouring of grief and love for Fresh was proof that the gaming community does care. From Austin to Dallas, I encountered the deepest hearts of Texas.

The rows of steel cubes and banks of computers in Dallas are empty and silent as I write these words. Ghosts of late-night Deathmatches fill that Southern space. The clouds have vanished and the Ion Storm has finally passed. In the end, I don't care what the online bitchers have to say. I was glad to be on my side of the keyboard rather than theirs. In case I haven't told you lately, John, thanks again for letting me share your dream.

It was hardcore.

Shares