Denesse Willey stands before a crowd of 35 high school students who have come to visit her small organic farm in California's Central Valley. The teenagers -- members of the Future Farmers of America -- chat, flirt and laugh. They squint into a morning sun that's just beginning to evaporate the dew on rows of fava beans and leeks.

"How many of you are considering a career in farming?" Willey asks.

"Do you mean agriculture?" says someone near the back of the group.

"No," Willey replies. "I mean producing, actual farming."

Only three hands go up.

Willey, all farmer in a pair of denim overalls and sunny yellow shirt, sighs with disbelief. "That's disappointing," she says. "We need more family farmers. We need more people on the land; more small and medium-sized family businesses."

Preacher-like rhythms and intonations begin to flow from Willey as she argues that there are clear-cut benefits to becoming the owner of a farm. It's not just that farmers tend to be especially active in their communities, "the coaches in Pop Warner, the parents on the school board," she says. It's also a matter of self-interest. Running a farm, according to Willey and her husband Tom, means gaining the greatest rewards from capitalism -- the freedom to define your own hours, your own eating habits, your own life.

"So I'm here to encourage you to become entrepreneurs," she says, finishing her 15-minute lecture. "I'm here to tell you to become business owners, not workers."

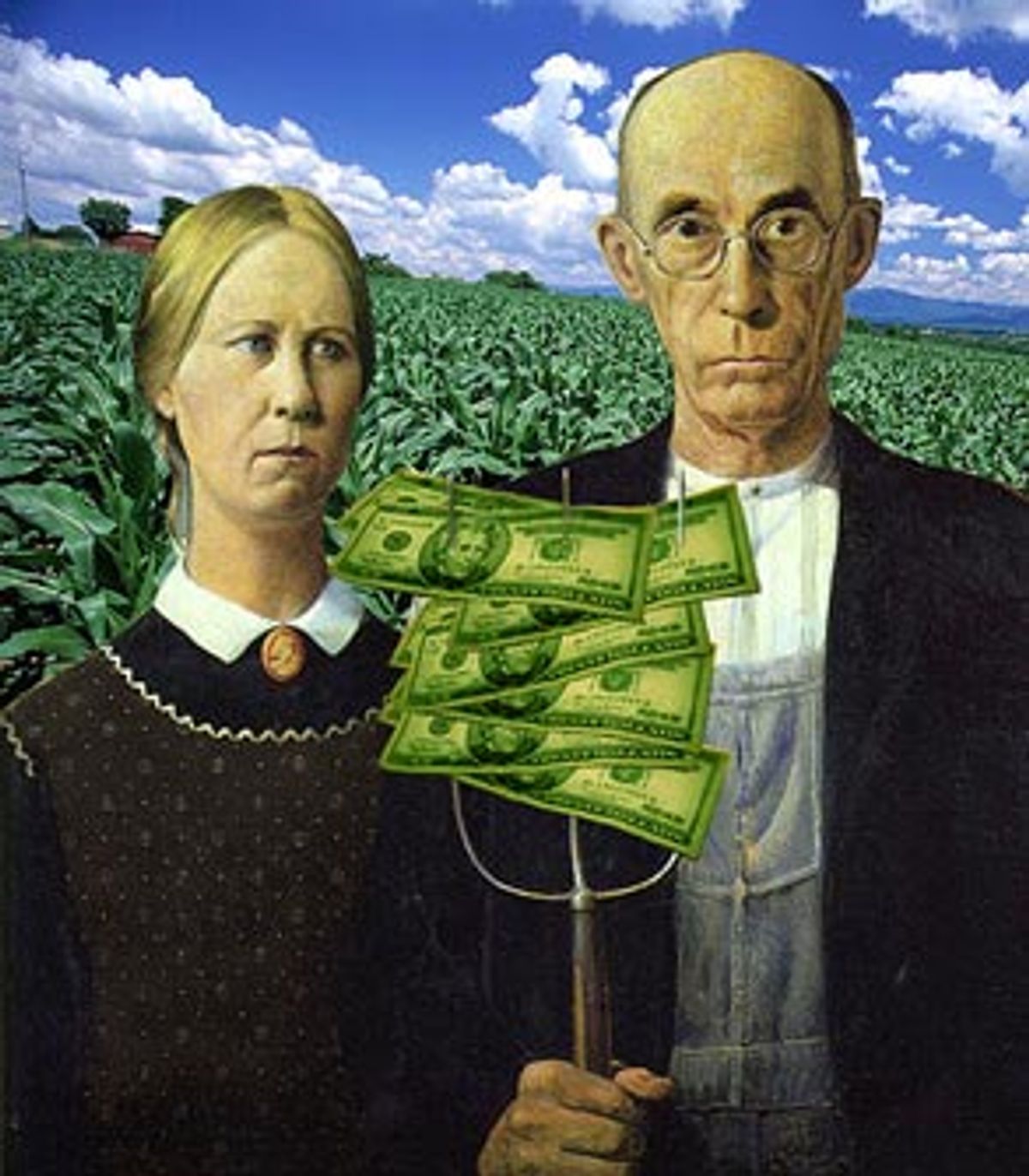

The cause for Willey's concern -- industrialization of the food industry and the gradual elimination of small farms -- is hardly new. Low prices and increased worldwide competition have been pushing independent farmers out of the market for generations; the '80s bust is now being followed by a 21st century implosion. But the Willeys stand out because they oppose what's become the standard solution, government assistance. In fact, by arguing for free markets and against subsidies -- in front of future farmers, in e-mails and in lectures -- they're setting themselves apart, cutting against the grain of politicians and most of their farming colleagues.

In 1996, President Clinton signed farm legislation that aimed to wean the industry from government subsidies, but today most people who concern themselves with farming are clamoring for cash. Industrial agribusinesses want increased subsidies to protect against low commodity prices. Organic farming organizations want the government to subsidize conservation. The California Department of Agriculture is even asking Congress to subsidize fruit and vegetable farms, which have always been left out of the subsidy packages that got their start during the Depression.

For the most part, Congress has gone along. Both houses passed farm bills earlier this year and on April 25, legislators -- anxious to win votes during a year of midterm elections -- finished combining the competing bills. If President Bush signs the proposal into law, taxpayers will pay out about $173 billion to farmers over the next decade. That's nearly a 50 percent increase over the last farm bill, and an amount roughly equivalent to what the U.S. spends on family welfare payments.

Which is far too much, according to the Willeys and a small but vocal core of critics. They remain convinced that help from the government only hurts owners of small farms; not only because they discourage entrepreneurship but also because subsidies are "a Band-Aid for a broken market," says Tom Willey. If politicians really wanted to help farmers, he argues, they'd eliminate every last dime of assistance from the farm bill's budget and fight harder for free-market reforms.

"Subsidies distort everything," he says. "Usually, a farmer produces according to what people want, but subsidies give an incentive to produce what the market doesn't need. And once you go down that road, you end with greater distortions: the mess that we're in now."

Willey doesn't object to the original intent of farm subsidy legislation. When farm subsidies were first established in the 1930s, they protected farmers by mainly subsidizing staple crops: rice, corn, wheat and cotton, for example. These crops were at the center of American agriculture at the time. By protecting them, Willey says, the country showed farmers that the country appreciated their efforts.

"They were trying to create a parity system," Tom Willey says. "They were saying that a bushel of corn has intrinsic value -- that an hour of a farmer's labor is as valuable as a factory worker's."

The farm bills continued to focus on farmers' pay for the next 30 years. "In the '50s farmers earned 50 or 60 percent of the average American income," says Bruce Gardner, an agricultural economist at the University of Maryland. "Subsidies were a way to help them out."

During the 1970s, the combination of oil shocks and rising food prices shifted the focus toward security. A stable food supply, homegrown and low-priced, became a common theme in the rhetoric surrounding farm bills, which typically came up for a vote every five to seven years. Food subsidies became a matter of security, not just economics.

Through the 1980s and early 1990s subsidies continued, but with an increasing level of discontent. By the time the Willeys bought their 75-acre farm in 1995 for $280,000, a handful of critics began asking why large companies seemed to get most of the subsidies while small farmers lost out. And as deregulation became the rule of the day, calls for reform began to sound. Farmer incomes had risen to the national average; subsidies came to be seen as vestiges of the past.

The turning point came in 1996 when President Clinton signed the Federal Agricultural Improvement and Reform (FAIR) Act and the Freedom to Farm Act. The laws looked like a stab at major reform. They dismantled the old system; the government stopped paying farmers to keep land fallow or grow certain amounts and instead simply gave them set amounts of money based on what they had grown in the past.

"The 1996 farm bill was a dramatic departure from traditional farm bills and programs," says Neil Ritchie, a national organizer for the Institute for Agricultural and Trade Policy, a nonprofit farming think tank. "The theory was that they were going to take away the subsidies programs; give direct payments for seven years, until they phased them out. Then the system would be free from the shackles of government and farming would work according to free markets."

At the time, commodities prices were relatively high. Farmers didn't mind removing the safety net when they were earning money, particularly when books like "Who Will Feed China?" suggested that the market for American exports would continue to grow faster than a field of weeds. But then the commodities markets collapsed. The Asian financial crisis sapped demand; countries such as Mexico and Brazil ramped up production and flooded the market.

Congress responded by bailing out the farmers with emergency assistance. This proved to be even more expensive than the older system of subsidies. In fact, direct payments to farmers soared in the late 1990s to more than $20 billion per year, up from an average of $9 billion in the early '90s, according to government figures.

The crisis continues to this day. For some commodities, prices are still nearly half what they were in the early '90s. The new bill, supporters argue, is an attempt to help farmers cope with this problem while avoiding the high price tag that results from last-second financing. Subsidies don't represent a lack of faith in free markets, they argue, but rather an acceptance of the market's status quo.

"The whole problem with the Freedom to Farm idea is that there is no free market," says Bruce Rominger, owner of a 3,000 acre farm in Yolo County, Calif. "You can put some farmers into a free market, but there are subsidies all over the planet. The European Union has large subsidies; Japan has incredibly large subsidies. So do other countries. It's not a flat and level playing field. It's unrealistic to think you can take away the protection in the farm bill and think everyone is going to be fine."

Rominger's farm, partly owned by his father, former Clinton administration Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Richard Rominger, earns several thousand dollars a year in subsidies. But, Rominger argues, other farmers also benefit from the cash the he and others earn.

"If you're in the San Joaquin Valley, and cotton doesn't look good, you're going look at almonds and other crops," he says. "Without subsidies, you'll go into the specialty crops and oversupply the market."

All farmers benefit from subsidies, he argues. "Even though the subsidies go to just a few of the commodity growers -- the people growing wheat, corn and rice, for example -- the benefit spreads throughout agriculture."

Legislators seem to agree. Asked who will benefit from the farm bill, after Congress completed negotiations on the bill, lead House negotiator Rep. Larry Combest, R-Texas, said simply: "I'll tell you who wins: the American farmer."

Most economists agree that a removal of subsidies would to some degree wreak havoc on America's small farmers. The question is, how much havoc?

Some experts expect a situation similar to what happened in the 1980s, when thousands of farmers lost their land due to a sudden drop in commodity prices and high interest rates, which made their debt particularly onerous. "If Congress would have said, 'Ah, screw it, the hell with the farm bill,' then you would have had an amazing amount of dislocation," says Sumner at UC-Davis. "You'd have farmers struggling to pay their landlords because they were locked into contracts that had prices based on the assumption that they'd be receiving subsidies. It would have been chaos."

Sumner figures that it would take at least three years for the market to stabilize. But the adjustment, others counter, wouldn't be nearly as painful or overwhelming as the crisis of the '80s. "It wouldn't be as big of a shock because in the '80s, commodity prices fell almost in half. Without subsidies, the payments would drop -- for those in the worst-case scenario -- by 30 or 40 percent. And if you spread the effect all over the land [to those who don't receive subsidies], there would be about a 15 percent change in revenues. Plus, farmers' debt isn't as high as it was in the '80s and land prices haven't been bid up as high as they were then."

"It would be a problem," he adds. "I don't want to minimize it. But it wouldn't even be half the magnitude of what we had in the '80s."

And regardless, even those who see the subsidies as short-term necessary assistance argue that an end to subsidies would ultimately help minimize oversupply.

The House's original farm bill, before amendments, weighs in at more than 200 pages and contains more than 60,000 words. The idea that so much legislative effort doesn't tamper with the market strikes most economists as ludicrous. Regardless of whether legislators have good intentions, their results continue to damage the markets that they purportedly seek to help.

Specifically, "subsidies have continued to encourage production and have driven down the marketplace," says Ronald Knutson, an agricultural economist at the University of Texas A&M. "Consumers are enjoying cheaper food than would otherwise exist but land prices are being bid up due to subsidies."

Subsidies distort expectations. Landowners calculate their land's value based on projected income, so because subsidies make the land more profitable, the owner can charge more money -- making the land more expensive for future farmers who want to get started. It's essentially a redistribution of wealth, with the money mainly going to already wealthy landowners. When the government is already running in the red, and when farmers now make as much as the national average income, if not more, do subsidies make as much sense as they once did?

No, say many economists. And, they say, taxpayers need to ask questions. "Do we want to be giving federal dollars to landowners?" asks Daniel Sumner, professor of agriculture and resource economics at the University of California at Davis. "People who are not poor people by any stretch?"

The subsidies don't just carry social and taxpayer costs; there are also signs that subsidies only lead to more subsidies and more economic trouble.

"These situations are difficult to get out of," says Knutson. "Subsidies lead to higher subsidies due to higher costs, lower prices and less competitiveness internationally."

Other countries, particularly those with crops to export, also won't be pleased with the U.S. decision to raise payments to farmers, says Richard Rominger.

"It hurts our ability to open the world up to free trade, to create robust new markets," he says. "We talk free trade and yet we increase our payments for production and at the same time we're slapping tariffs on steel and lumber. And the textile industry wants to keep tariffs too. This is a big problem, particularly for the developing world."

To some, the farm bill is nothing more than a hodgepodge mix of mistakes, a snowball that's collected together decades of failure. "What we have now [with the farm bill passed by Congress] is a mix of the failed policies of the '30s to the '80s, on top of the Freedom to Farm payments of the '96 bills," says Susanne Fleek, director of government relations for the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group. "What farm bill negotiators have said is that if we combine two programs that failed to work, we might get success. Let's throw more money at failed policies and hope for a different outcome."

The Willeys tend to agree with most, if not all, of these criticisms. But living day-to-day on the land, working six days a week, 10 hours a day, they stress the more subtle, psychological toll that subsidies take. The farm they run hasn't made them rich; on $1.5 million in sales last year, the Willeys made about $100,000, which is about average for their farm. But they're clearly proud of what they've achieved. They speak energetically about how they work as a team (Denesse does most of the marketing; Tom handles day-to-day production.) They sound like teachers when they explain that by using four fields -- and harvesting each in a different season -- they can hedge against price fluctuations while also keeping their 30 employees on the payroll full-time. And they clearly revel in giving tours. During my visit, they insisted on walking the future farmers through their fields, despite the fact that Tom has a pronounced limp -- and to the chagrin of one teenager who had a cast on her leg.

In other words, they see themselves as embodiments of the American dream: capitalists, entrepreneurs, community activists, parents, friends. Subsidies then only insult their hard work and the hard work of others like them. The payments make it harder for them to compete in the marketplace, by adding to the bottom line of the large companies that keep buying out small farmers. Worse, the payments make hardworking farmers feel like weaklings, they say.

"Subsidies are a welfare system," says Tom Willey. "And it's degrading, actually. When you see how hard farmers work, it's crazy that at the end of the year they have to ask the government for money. It's disgusting."

Willey remembers feeling embarrassed a few years ago when local stores gave discounts to farmers. The 5 percent cut in prices might have helped his wallet but it hurt his pride. "Just pay us a decent price for our food and we'll be fine," he says.

Denesse agrees. "I'm in favor of a high-priced food policy," she says. "I just want a fair price for my food."

Their pitch won over at least one person on the tour. Charles Gustafson, a chaperone and high-tech entrepreneur, said that before meeting the Willeys, he was wondering whether their farm -- with its organic focus -- was some kind of commune. But at the end of his visit, just before getting back on the bus, he could barely contain his effusive praise. "This is capitalism at its finest," he said. "This is pure entrepreneurship; America's best."

A handful of influential observers agree; the Willeys are not completely alone in their quest. Richard Rominger, for example, also acknowledges that "we're not paying enough to cover farmers' costs," and says that "we have to figure out some way to pay farmers for protecting their resources while they're producing the food." (One aspect of the farm bill -- an increase in funding for farmers who take part in land conservation -- helps protect the land but, he says, completely ignores the larger issue of setting fair prices.)

But will America ever really change the way that farmers are forced to do business? Will there be any more farmers to protect if and when subsidies are eliminated? Two of the future farmers who visited the Willeys didn't offer much hope for those who would like to see more small farms proliferate. When asked if they would consider a career in family farming, both Chris Jougin, 15, and Whitney McMasters, 16, said no. Sure, the Willeys seemed happy and competent, they said. But small farms are too risky.

"The failure rate is so high," said Jougin.

"Yeah," added McMasters. "It's just so hard to succeed."

Shares