On April 15, Jimwich's Fotolog featured a remarkable close-up of a full moon, milky-gray with muddy craters against a deep black sky. Because the focus was less crystalline than his usual work, Jimwich explained in a comment below the picture that he shot it through binoculars, "a somewhat unwieldly setup." But a long ribbon of additional comments from visitors registered no complaints: "amazing shot," "unbelievably pretty."

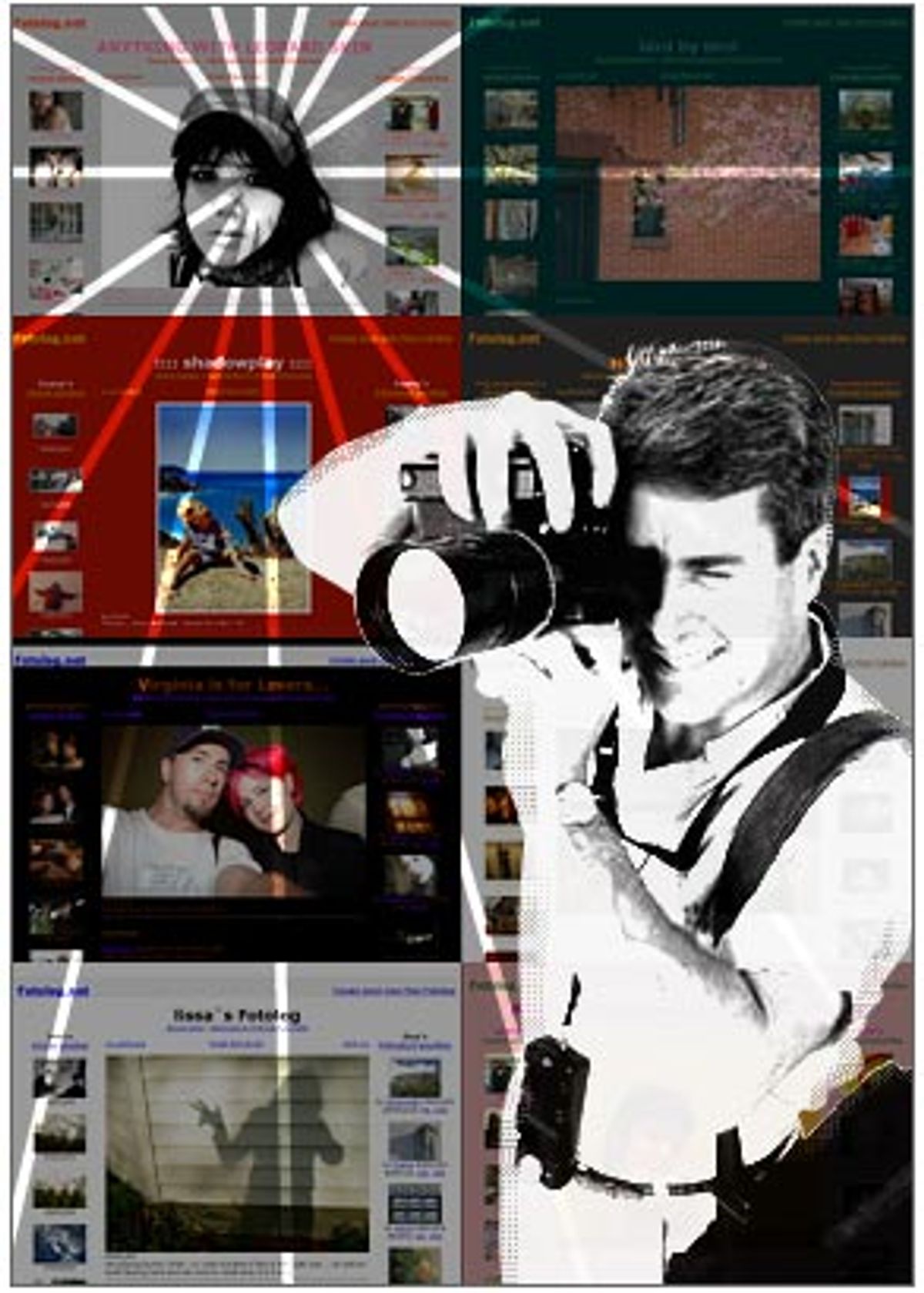

Thumbnails running down the left of this Web page link to Jimwich's other recent photos: bright mosaics against a brick wall in Mountain View, Calif.; a lowering watertower; a bee descending toward a flower, every pollen crumb in its fur caught with hallucinatory sharpness.

To the right, more thumbnails link to other Fotolog pages -- Jimwich's "Friends/Favorites" list. These are updated constantly as the pages they link to change; on this day, they include a blossoming fruit tree in central France, rusty New York City buildings in a limpid dawn, and an unusually crisp phonecam self-portrait taken in Berkeley, Calif.

A click on any of those links leads one deeper into a Net-enabled nexus of a newly-invigorated arts scene. With the advent of the digital camera, the life of an amateur photographer has been made easier than ever before; now, with the help of community sites like Fotolog, photography is experiencing a full-fledged grass-roots renaissance.

Founded less than a year ago by Web entrepreneur Scott Heiferman, now managed by software consultant Adam Seifer and a "tech whiz" who prefers to be known only as "Spike," Fotolog is a network of blog-like visual journals. As its FAQ states, Fotolog is not an Ofoto-style online album, where you upload all 40 shots of your family reunion so your cousins can order prints. Instead, at Fotolog, users have created an intriguing international community of photographers, mostly amateur, who post one or two photos to visual blogs every day or every week, allowing friends, family, and random visitors a brief glimpse into their worlds.

Something about this concept resonates, because the site is experiencing crazy growth. In less than a year, Fotolog has gone from 50 new users a month to 50 per day, and the rate is increasing,

Seifer believes that one of Fotolog's strengths is that "anybody with a camera can take a great photo." If you have suffered through one too many vacation albums, you know that's overly optimistic. And yet besides the inevitable blurry, red-eyed picnic shots, Fotolog abounds with beautiful and extraordinary images like those on Jimwich's page. Why is that?

In part it's because digital cameras have made not just photography, but photographic art, much more widely available. When novice photographers can see their pictures immediately, it sharply accelerates the learning process. But more than that, digital cameras eliminate the expense of film and development. You can shoot and re-shoot, experiment and play, for no more than it costs to recharge a few batteries. This luxury was previously available to few besides professional photographers. Digital cameras have liberated infinite fertile mistakes.

At the same time, the act of keeping a photographic record of your daily life teaches you to see with a different eye. "Once you start carrying a camera around with you, you see the world in a new way," says Seifer. "You start noticing everything around you. Walking to the subway is no longer about the time you're 'losing' on your way there -- it's an opportunity to see thousands of potential photo subjects."

What Fotolog specifically adds to the mix is feedback. The Friends/Favorites lists and the comment feature allow users to share their work with others to a much greater extent than a lonely, disconnected Web page with personal photos could. The community provides ongoing feedback and constant exposure to the work of others. And that changes the way people make their photos. Seifer says, "We find that a lot of our users start off posting pics from their vacations and birthday parties, since that's all they've ever done, and little by little, as they see which other photos on Fotolog tend to get the most enthusiastic attention, it inspires them to start being more thoughtful and experimental with their own photos. It's a very satisfying dynamic to observe."

The seeds of Fotolog first emerged when Heiferman sold his Web advertising company, i-traffic, in 1999 and began casting around for a new project based on the community-building power of the Internet. "While people were writing off the Web," he says, "I was falling in love with the new world order of riffraff-free community and self-publishing on the post-bubble Web: blogs, LiveJournal, Craigslist, Fark, eBay, Allyourbase."

Wanting to do a blog, but not feeling like a writer -- and inspired by photography sites like lightningfield.com and lauraholder.com -- Heiferman started posting a photo a day, a practice he now continues in his own Fotolog.

When Heiferman decided to focus his efforts on Meetup.com, a site that helps organize face-to-face meetings among local interest groups, he passed along another idea to Spike -- "I gave him my sketches, he made it" -- and Fotolog went live in May 2002.

Adam Seifer was an early Fotolog user who shared Heiferman's interest in "viral community growth." Seifer's Foodlog is an inexplicably entrancing visual record of what he eats every day ("not everything -- just the major meals") -- a piece of performance art celebrating the color values inherent in rotini with fra diavolo sauce. Seifer became "completely obsessed with the Fotolog concept," and Spike and Heiferman eventually put him in charge.

Spike built the site itself using open-source software technology -- a conscious choice that Seifer hopes will help them "leverage the years of scaling Web sites that we've learned from previous jobs." The site is growing very fast indeed. In its first five months, it was intended only for the use of the founders' friends and family. But with some tweaks to the site last October (Seifer calls them "more and better viral mechanisms for people to get their friends involved"), membership took a sharp upward turn. As of April 2003, Fotolog had over 3,000 Fotologgers. "It took 10 months for us to reach our first million total Fotolog views," Seifer notes. "We've served over a million Fotolog pages in the last three weeks." Currently Fotolog is free to users, though the site requests donations, and Seifer, Spike, and others run it in their spare time.

The site's design is simple and intuitive. Each Fotologger has his or her own page, with the most recent photo prominently displayed and a space for comments underneath. The Friends/Favorites thumbnails act as the site's organic, semi-chaotic, and entirely human organizing principle. Browsing the site is delightfully unpredictable, an experience of repeated serendipity. Clicking one link begins a sort of "drunkard's tour" of the site, as Fotologger and Los Angeles screenwriter Howard A. Rodman puts it, in which you poke your head down one interesting alley, see a friend and backtrack in that direction, meet someone new and wander off with them, etc.

And since photography transcends language differences, your new friend may well be from the other side of the world. Fotolog is more truly international than most Web sites, with members from 70 countries, from Iceland to Singapore to Brazil. Comments in Portuguese and French are common. Fotologger Yolima photographs the red roofs of The Hague against a bright blue sky. Virginie is from France -- her Fotolog recently featured an eerie series of angelic, childish limbs in different poses. New Yorker Digiruben, who recently photographed a bare tree against a shocking pink wall, features a Friends/Favorites list that links to Fotologs from Battle Creek to Tokyo to Lyon.

With thousands of windows into thousands of worlds, Fotolog makes visitors into voyeurs -- not in the sexual sense (Fotolog's user agreement forbids vulgar or obscene material), but in a psychological one. Browsing Fotolog, you see not just into people's lives but into their minds -- a "glimpse into their cognitive landscape," as Patrick Lopez, an Austin, Texas, Fotolog fan, calls it. We all see selectively, making choices from within the world's visual riot, and those choices say something about us. One glance at any Fotologger's thumbnails tells you where, consciously or unconsciously, they choose to focus their gaze: on themselves (this appears to be especially common among adolescent Fotologgers), the natural world, on abstract arrangements of color and light, etc. The photos also tell you something about how they see, whether in passionate blurs or with scrupulous clarity. Every Fotolog has a different visual voice, and the best have distinct and extraordinary ones.

Within Fotolog, subset communities are beginning to emerge -- for example, those who shoot with cheap low-res cameras like the Blink -- and the site will do more to encourage such communities in the future. Seifer is also proud of the technology that allows those with cellphone cameras to e-mail their photos directly from the street to their Fotologs. "There's a sense of immediacy and 'realness' that you just don't get from nicely PhotoShopped art shots," he observes of this "personal photojournalism."

All this is not to say that everyone who starts a Fotolog becomes Ansel Adams or Dorothea Lange. But the construct of godlike artist reaching down to the audience from on high is ready for a rest now, anyway. Passive consumption of art and entertainment -- so 20th century! The ease of self-publishing on the Web (and Fotolog makes it extremely easy) encourages participation. As a result, the Internet is becoming a lush, messy, and pleasantly neglected garden, one where all kinds of art forms -- blogs, photologs, Flash art, films, music -- can flourish.

With luxuriant growth come challenges, of course. Seifer is confident of Fotolog's ability to handle its intense expansion, saying, "We've tried hard to architect the site to be scalable from the get-go." They also recently established an upload limit of six photos per day to deal with "people misunderstanding what Fotolog is about."

And Fotolog's donation system "has been great so far," Seifer says. "I think that after the dot-com bust, people have come to understand that the online content and services they enjoy simply won't be provided for free indefinitely." It may also be that Fotolog users feel a special interest in keeping this particularly fertile corner of the Internet garden alive.

Shares