The first thing you should know about Marshall Brain is that he is not, despite his dim take on the future, a Luddite. To people who've read some of his essays, this is hard to believe, but Brain, a 42-year-old businessman and father of four who lives in Raleigh, N.C., has always been passionate about technology. In college, Brain studied computer science and electrical engineering. He went on to start a computer consulting firm and to write several programming manuals, and then, in the late 1990s, Brain jumped on the dot-com gravy train. He created HowStuffWorks.com, an ingenious collection of Web pages that explain everything technical under the sun, from light-emitting diodes to limited slip differentials to Botox.

The second thing you should know about Marshall Brain is that he is gravely concerned about the ongoing tech revolution. Perhaps because he has so much faith in technology, Brain sees no bounds to its progress, and he believes that within a short time -- two or three decades -- machines will be capable of doing much of what humans do now. In the past year, Brain has written a series of widely discussed essays and five chapters of a science fiction novel exploring this question: What will become of human society -- especially the economy -- when robots take all our jobs?

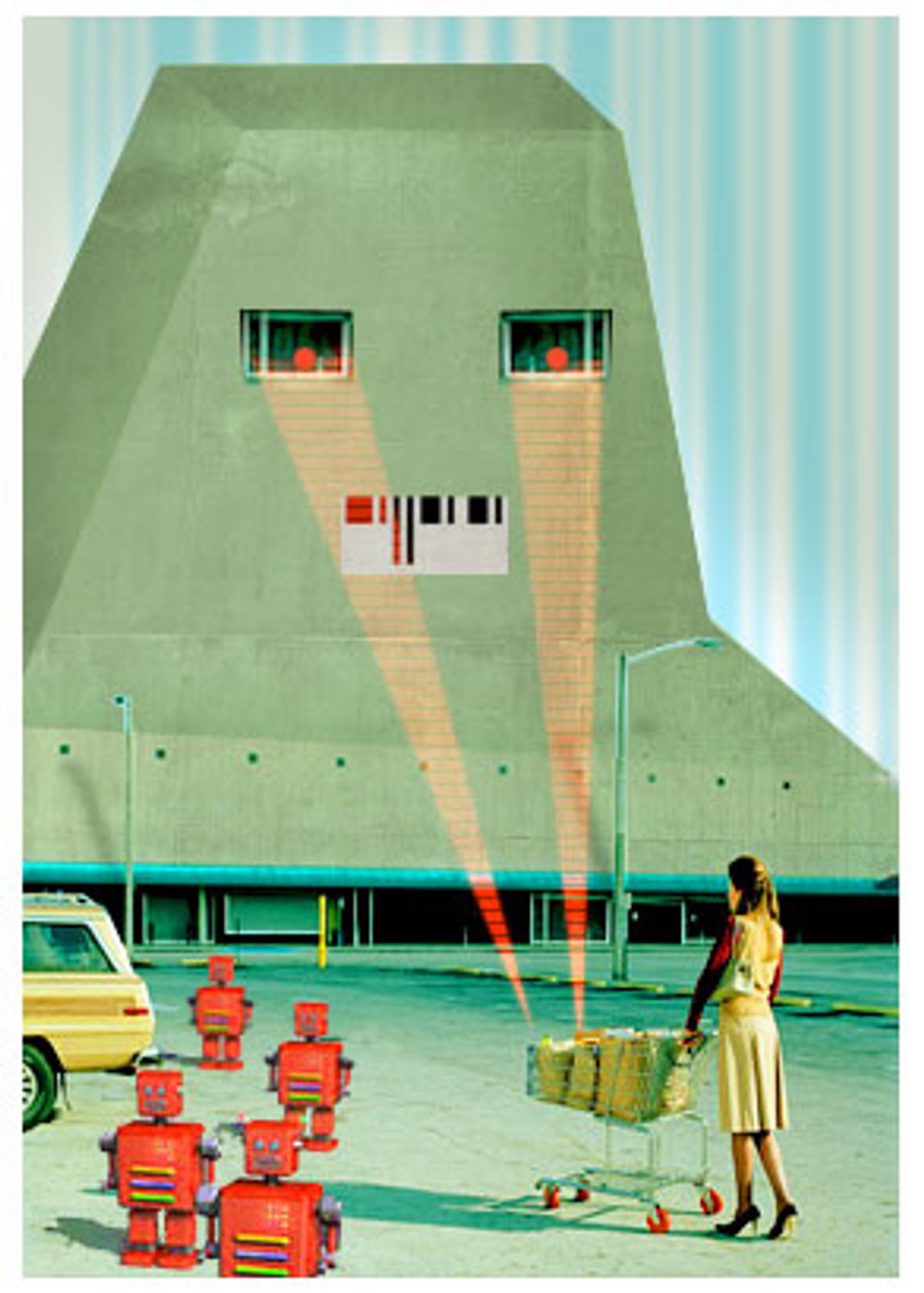

It might seem premature to begin worrying about competing for jobs with robots, but Brain is not just thinking about C-3PO and R2-D2. He points out that "primitive" robots -- in the form of ATMs, pay-at-the-pump gas service, self-checkout machines at supermarkets, boarding-pass kiosks at airports -- are among us already. These systems can provide profound benefits to society, but Brain believes that we must institute a series of progressive economic policies to make sure that the "roboticization" of our jobs does not cause massive destitution.

Is Brain right? Will technology send us to the unemployment line? In general, economists have a hard time answering this question. The relationship between job growth and productivity growth is complex, and even during today's "jobless recovery" economists are arguing about whether recent productivity gains are helping or hurting Americans. But one thing appears certain -- many of the jobs we rely on today will soon vanish from the American landscape.

"Technology is continuing to eat away at any routine services," says Robert Reich, an economist at Brandeis University who served as President Clinton's first labor secretary. "Anything that can be done by software, or by someone in China or India or the Philippines, is not going to be here. It will not pay a person to do it."

Whether you think this is a good thing or a bad thing probably has a lot to do with whether your job will soon be automated out of existence.

Marshall Brain's ideas are not completely novel -- Bill Joy, Jeremy Rifkin, Raymond Kurzweil, Hans Moravec and others have been ruminating on the pros and the cons of robotic society for years. But Brain's essays come at a particularly low point in the U.S. economy; after more than two years of constant job losses due to recession, automation, globalization and other forces of economic nature, Americans are probably quite ready to believe, these days, that bad times are here to stay. Job losses due to productivity gains in the manufacturing sector -- in automobile factories, steel plants and textile mills -- are already an old story. Soon, workers in the service sector -- in, say, retail shops, restaurants, construction sites and all sorts of others that have so far been relatively unaffected by automation -- will become as replaceable as the poor souls working in manufacturing.

Brain writes that in about 10 years, "every big box retailer will be using automated checkout lines. Robotic help systems will guide shoppers in the stores. The automated inventory management robots will allow the first retailer to lay off a huge percentage of its employees. Competitive pressure will force Wal-Mart, Kmart, Target, Home Depot, Lowe's, BJ's, Sam's Club, Toys 'R' Us, Sears, J.C. Penney, Barnes and Noble, Borders, Best Buy, Circuit City, Office Max, Staples, Office Depot, Kroger, Winn-Dixie, Pet Depot and on and on and on to adopt the same robotic inventory systems in their stores." Fifteen million people work in retail in the United States, and Brain guesses that automated systems will put 10 million of them out of work.

But retail-industry experts do not agree with Brain's analysis; while cost-obsessive retailers like Wal-Mart could very well automate everything in their stores (Brain insists that the "robotic Wal-Mart" is not far off), higher-end retailers aiming for better customer service will probably still find use for humans. Indeed, according to people who've studied the introduction of self-checkout systems in supermarkets, cashiers being replaced by these machines are not being let go. Instead, companies move these people to other parts of the store, where they can better help customers find what they need. Even the United Food and Commercial Workers, the union that represents workers at A&P, Safeway, Kroger, Albertson's and many other large supermarket chains, says that it has not seen any losses due to these machines -- so far.

And this provides a good glimpse of what work will look like in the future. Instead of scanning and bagging someone's groceries, perhaps it'll be your job to walk a shopper through the store and help him choose the perfect wine or cheese, or maybe you'll just be stuck watching the customer's screaming 2-year-old while the shopper decides on gourmet olives. Reich says that, increasingly, low-end jobs will be in this "personal service" category; massage therapy and childcare are two growth fields he points to. The rest of us, if we're lucky, will find work in what some people call the "knowledge business" -- "in enjoyable but unessential activities like writing Salon articles and robot books," as Hans Moravec, a robot scientist at Carnegie Mellon and the author of the book "Robot," put it in an e-mail. These activities, Moravec suggests, will not easily be replicated by machines. Here's hoping.

Few tasks seem as well suited to robots as those performed by cashiers at a retail checkout counter. Cashiers' jobs are marked by a single simple, repeated activity -- passing an item in front of a computerized scanner -- and to excel at it, the best people probably have to be a little bit robotic themselves, scanning items quickly, efficiently, accurately, never allowing such human failings as exhaustion or annoyance to peek through.

In the 1990s, after noting the success of ATMs and pay-at-the-pump gasoline, several technology firms began looking to supermarkets and other retail outlets for the next self-service revolution. The companies guessed that shoppers would readily accept self-service machines. "Some consumers say that the shopping environment is so depersonalized they feel they might as well engage with technology," says Mike Webster, the general manager for self-checkout systems at NCR, whose machines are now installed at Home Depot, Kmart, Wal-Mart and other stores. In the past, cashiers "used to know your name, they'd ask how your kids are doing," Webster says. Cashiers don't talk to you anymore, and customers wonder why they need this stranger to scan their items for them. Some people feel they "would best be left alone."

Self-checkout systems are foolproof to use. You walk up to a machine, scan your items (a scale is provided for items sold by weight), and pay with cash or credit. That's it. The machines operate in the mode of most other self-service technologies we're used to, with on-screen prompts helping you along the way, just like on an ATM. Experts point out that the machines are not actually faster than a human teller -- but because they're always available, they typically have shorter lines than express lanes at stores, and because customers are actively involved in the scanning process, self-checkout seems quicker.

Because most supermarket shoppers are already familiar with other self-service technologies, many find self-checkout naturally appealing. In a survey he conducted in August, Chris Boone, an analyst at the technology research firm IDC, found that 80 percent of retail customers would use a self-checkout system if one was available to them. The appeal was not limited to a specific demographic set, Boone says -- even old people liked the idea of self-checkout. Many customers who've used it say that self-checkout makes shopping faster and more convenient, especially for small purchases. Mike Webster, of NCR, says that the systems are also useful for people buying things they "might deem to be sensitive. If I have concerns over my privacy, I would just as soon use self-checkout." And if you're someone who has a hard time trusting the cashier, self-checkout is for you. "There are groups of people that use self-checkout to go slower, to make sure that they have all the discounts and coupons coming to them," Boone says.

In most shops, one employee is charged with monitoring a collection of about four self-checkout machines. The attendant is there to help shoppers new to the system, and to watch out for stealing (many systems have built-in security cameras that the attendant can access). In theory, then, since the machines allow one person to do the work of four, self-checkout systems give stores a great way to cut down on labor costs. Technology firms usually sell the systems to stores by promising labor savings. But that's not how things have worked out, experts say.

There was a time when ringing up groceries was the brightest job in the retail firmament -- when the salary for these positions was "the crème de la crème," says Greg Buzek, the president of IHL Consulting Group, which helps retail companies choose self-checkout systems and other technologies. But the days of high-flying cashier wages are long gone. Cashiers are often not paid much more than other retail employees; according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, their national average wage in 2002 was $8.19 an hour. At those rates, Buzek says, people don't see much glory at the checkout counter. "The same teenage girl that would have taken the job at the Kroger store has the opportunity to work at the mall at, say, the Gap," Buzek points out. "And wouldn't you rather work at the Gap?" Despite the high unemployment rate, Buzek says that supermarkets face constant labor shortages; and when they can cut down on labor needs at the checkout lanes, they redeploy their employees to other parts of the store. If people think self-checkout machines are "costing jobs," Buzek says, "that's not true."

Labor groups have a hard time believing that, however. Self-checkout systems will have a negative impact on the number of jobs and the number of hours worked in stores, says Greg Denier, a spokesman for the United Food and Commercial Workers. "This is a continuation of a trend to eliminate service in the name of consumer convenience -- at a certain point they may want to have the customers unload the trucks and stock the shelves, too." Denier says that checking out groceries is worthwhile work, and supermarkets that want to eliminate the positions in favor of machines are being shortsighted. He concedes that -- at least in the stores his union represents -- workers who have been replaced by machines have not been laid off because of these new machines. "The UFCW has worked with employers to protect the jobs of our members in our stores," he says. But Denier says it's possible that people could lose jobs in the future, as the machines become more prevalent. But he also thinks that before long, customers will insist on human cashiers.

"The only reason consumers may find self-checkout convenient is because stores create a situation where customers have no choice," Denier says. Stores deliberately understaff checkout lanes, Denier insists -- but it won't be long before customers rebel. "Full-service grocery stores will understand that their market differentiator is service," he says. "People who go to a full-service grocery store go there because they want full service. We've had situations where grocery stores have eliminated meat cutters, but they had to bring them back because the customers demanded it."

Are supermarket cashiers like meat cutters, or are they like bank tellers? Do they provide a unique, specialized, personalized service that customers think is worth paying extra for, or is what they do so automatic, so routine, that shoppers will see nothing essentially different when they deal with a machine? If you want to know whether your job will survive the coming age of robots, maybe you should ask this question of yourself. And if you realize that what you do requires nothing especially human, perhaps you should look into massage therapy.

For supermarket cashiers, the situation appears grim. Stores that install self-checkout machines find that each system pays for itself in about a year's time, according to a study Greg Buzek conducted. And contrary to the UFCW's theory, customers often say that service in stores improves with these systems; Chris Boone says that he knows of many stores that have installed self-checkout systems only because nearby competitors had done so. The Kroger chain, which was an early adopter of the technology, has installed about 5,000 machines in its stores, Buzek says, and it's planning on deploying many more. Kmart and Home Depot have also bet on the technology. Home Depot expects to have the systems in half of its stores by the end of 2003; a spokeswoman said that the stores have not let anyone go because of these systems. In the stores that have these machines, "anywhere from 15 to 40 percent of the daily transaction volume and 12 to 30 percent of the daily [money volume] ... is being handled by self-checkout machines," Buzek wrote in a recent study of the systems.

These numbers corroborate Marshall Brain's theory that humans will quickly adopt robotic help. "People love technology," he says. "It's faster, it's usually less hassle, it makes less mistakes. We would happily go to a robotic anything."

But, unfortunately for human workers, those lovable robots are getting better all the time. ASIMO, a robot created by Honda, can walk on two feet, just like humans. The thing is so lifelike that scientists in India have determined that, in addition to walking, ASIMO could be good for more intimate tasks. "One of the reasons for marital breakups today is physical inadequacy. Couples are so stressed out that there's no time for foreplay, so essential to get the juices flowing. A smart machine can bridge that gap in no time," Dr. CRJP Naidu of Bangalore's Centre for Artificial Intelligence & Robotics told the Hindustan Times. Not long ago, Brain saw an article in Popular Science about a robot scientist who'd created an extremely humanlike robotic face -- "a real face, with soft flesh-toned polymer skin and finely sculpted features and high cheekbones and big blue eyes," the article said.

Brain is on edge about this development. "Imagine," he says, "you walk into a restaurant and what appears to be a very attractive person is there to greet you. A robot with a database behind it would be so much better in terms of service than a human could be. There's no competition -- how could a fast-food worker who doesn't even greet you be better than a robot? In a store, you'll speak to a robot like you do to a human being, but it will have total information about everything in the store, it will carry your item out to your car, it'll be so much better. And this is what's so cool about robots. If you think about it, robots are a blessing -- no one's going to be scrubbing toilets anymore. But how do we deal with it?"

Robots have at least a few decades to go before they get as good as Brain says they can -- but the concerns he raises about them are perhaps allayed by a look at what retailers are doing with their employees after they've installed self-checkout systems. "Let's look at Kroger," Buzek says. "They've got over 5,000 of these machines out there. They haven't displaced a single worker, and instead they've added more people to the deli, to the cakes, to the fresh food department, and as such they've beefed up that customer service." When these workers manned checkout lanes, they provided no valuable service for customers -- they were a cost to the stores, Buzek says, because they only interacted with shoppers after all customers' purchasing decisions were made. Now they're in a position to help customers, and, of more concern to the store, to influence purchases.

Why are the stores doing this? Why don't they reduce their labor force in order to cut costs and become the lowest-price retailer in town? "That would be stupid," Buzek says, because most stores couldn't offer the lowest prices even if they tried. Wal-Mart -- which sells more food, drugs, toys, sporting goods and music than any other retailer in the world -- already has the low-price niche sealed up. Competitors to Wal-Mart have higher prices, but they offer their customers additional benefits, like better service or more well-designed products -- and for this these companies need human beings.

Brain, of course, believes that even in-store customer service tasks will eventually be performed by robots. But there are many tasks that would seem impossible, or at least undesirable, for robots to do. Would you want a robot taking care of your child? Would you want a robot nursing your aging mother? Would you want a robot working as a chef at your restaurant? Would you want to see robots playing tennis? If you tried on a suit at a store and a robot told you it thought you looked great, would you trust it?

"There are all sorts of jobs that can't be done by robots because the essence of the job is providing personal attention," Robert Reich says. These jobs can't be done by foreigners either, "because they require someone to be there in person." In the future, he says, a large portion of the American workforce will work in these fields. This is not an ideal situation. The problem, Reich says, is that many of these jobs don't pay very well -- but neither does scanning groceries.

At the same time, Reich says, "there is a continuing demand -- and the demand is increasing -- for people who can identify and solve new problems, who can innovate, who can create, who can discover, who are able to provide their companies or their enterprises with energy and competitive spark. These jobs -- in research and development, engineering, design, advance sales, marketing, advertising, legal services, financial services, all sorts of Web-based creative services -- these jobs take a hit in recessions but they are the many good jobs. They pay very well, and even if some may not pay handsomely, the psychic benefits are large."

Reich refers to these jobs as "symbolic analytic" jobs, because "a large number of them require the ability to manipulate and analyze symbols, whether the symbols are words, numbers or visual images." They require, in other words, a spark of human ingenuity and creativity, and these seem unlikely to be replicated in robots -- at least not anytime soon.

Tor Dahl, a productivity expert who served as the head of the World Confederation of Productivity Science for 11 years, is even more lyrical than Reich on the idea that the human brain, rather than our hands, will become the driving force of the economy. "I'm a proponent of the coming productivity revolution, which could well double wealth every 12 years instead of the historical 36 years," he wrote in an e-mail.

"Who will get this wealth? Knowledge will. Who are the owners of knowledge? Well, if corporations are, that will be mainly pension funds and American households. It will not be the robber baron template of the Industrial Revolution. Knowledge largely rests in human minds. Marxism has now been turned on its head: The means of production rests in the minds of individuals. Having abolished slavery, these individuals now own the means of production. The workplaces of the future will have invisible balance sheets for most of their capital, unless they somehow find a way to measure and include human capital."

Dahl adds: "A productivity revolution will usher in an earthly heaven, albeit a materialistic heaven. It's our only real chance to address and remove the old scourges of mankind: Hunger, disease, poverty and war. People always get nervous when prosperity beckons this side of heaven."

Both Dahl and Reich concede that adjusting to this new economy will not be easy for everyone; when jobs that have been abundant vanish, workers who've spent their lives in those jobs won't easily find something new to do. In the short term, this creates problems -- not the least of them political. We're currently seeing something like this in the U.S. manufacturing sector, which has lost almost 3 million jobs in the last three years. Both Democrats and Republicans are trying to appeal to voters in manufacturing states by showing that they're at least trying to create new factory jobs. On Monday, Don Evans, the secretary of commerce, announced that he was creating an unfair trade practices team to monitor trade violations on the part of U.S. partners (the administration's biggest suspect is China) and a new secretarial post to look into ways to promote domestic manufacturing.

"It's bullshit," says Reich. "Trying to protect certain manufacturing businesses by putting up tariffs and subsidies postpones the day of reckoning. Technological change and globalization are hugely powerful forces. We don't want to go back to the days of the Luddites and destroy the machines. You have to remember that it's not as if there's a finite number of jobs in the world economy to be divided up between us and them."

The answer to the threats posed by automation and globalization, argues Reich, is not to try to be defensive, to put up protectionist walls and lavish subsidies on threatened industries, but to be aggressive, and help people find new jobs. But right now, government support for training programs of the kind necessary is minimal.

"Of course, some people get slammed; some people are getting slammed in this jobs recession which continues on," says Reich. "If you're a 55-year-old assembly line welder and you lose your job because there's a computerized system for doing that welding or because it can be done in Southeast Asia, we don't have a pathway for you, we don't have enough insurance, our training programs are few and far between and underfunded. We don't have an easy route for you to find out what you need to learn. We don't have any of those adjustment mechanisms, and those are critical in an economy that is changing as rapidly as ours. It's cruel and unusual not to help people get the skills they need, the information they need, to get a new job."

Shares