In the real world, Peter Ludlow is an academic, a professor of philosophy and linguistics at the University of Michigan whose books go by sober titles like "Readings in the Philosophy of Language," and "Semantics, Tense and Time: An Essay in the Metaphysics of Natural Language." He's well-regarded in his field and engaging enough on the phone, but Ludlow is, even by his own admission, not a very interesting person. That is to say, Peter Ludlow is nothing like Urizenus, Ludlow's alter ego in the virtual world of "The Sims Online."

Urizenus is an unabashed muckraker. In the mold, perhaps, of Walter Winchell or Joseph Pulitzer, he investigates the shady underside of life in Alphaville, one of the game's largest cities, and posts all his sensational discoveries on the Alphaville Herald, a blog that he describes as the only newspaper covering "The Sims Online." In the couple of months since the blog went live, Urizenus has interviewed many of Alphaville's most infamous scammers, thieves, money launderers, prostitutes (some of whom, he says, are minors) and other dubious types, and he's documented attempts by the community to create a kind of governing authority to police the place.

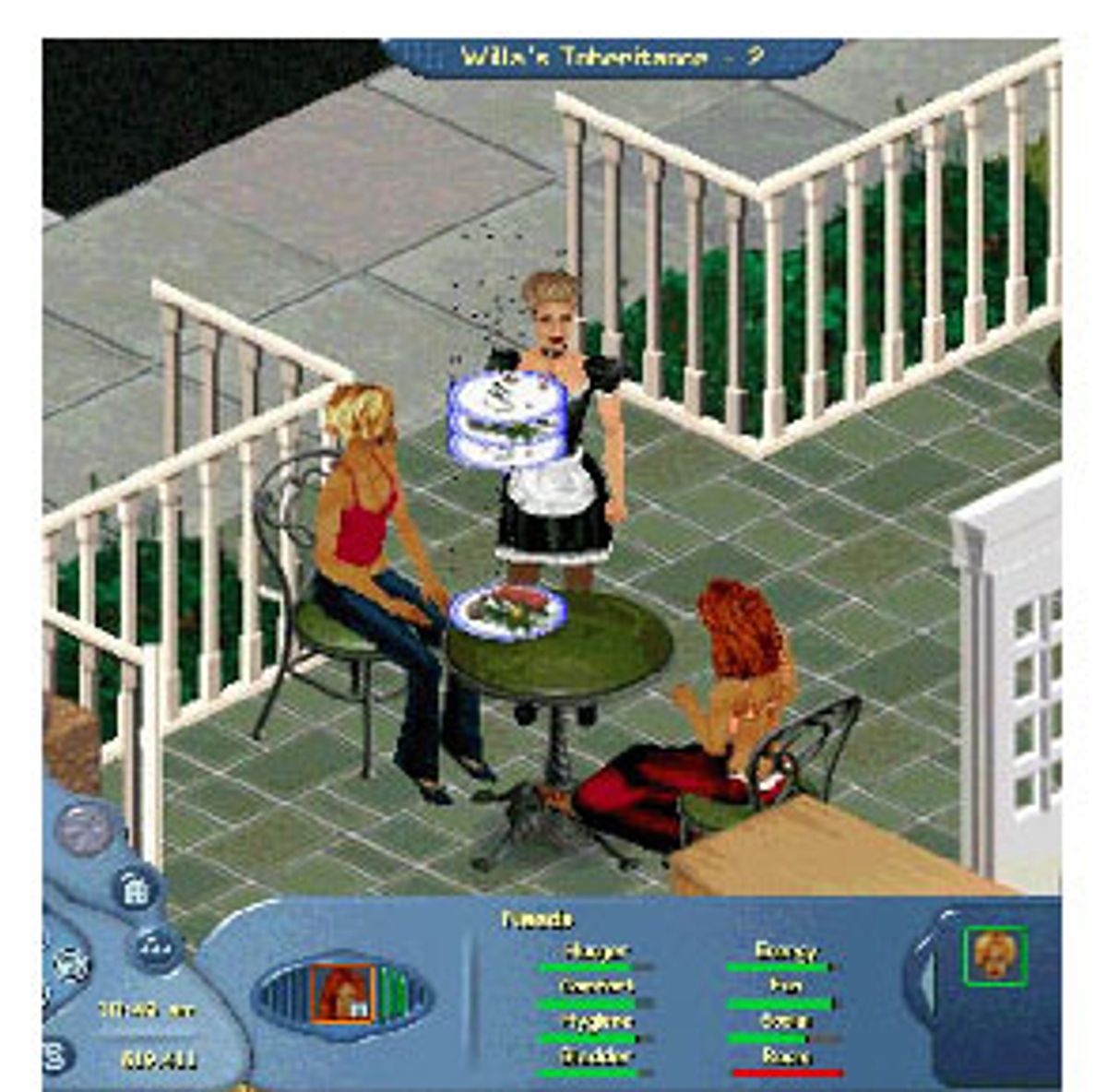

Urizenus and his compatriots at the Herald have also aimed their bullhorn at Maxis, the company that created "The Sims Online" and that runs the place; in blog entry after blog entry, the Herald describes Maxis as being signally indifferent to the needs of people who populate the game, and it documents the many reasons why "The Sims Online" -- which was predicted to be a blockbuster and made the cover of Time magazine before its launch late in 2002 -- has been a money-loser for Electronic Arts, Maxis' parent company.

But the Herald's relentless criticism does not appear to have gone down well at E.A. On Wednesday, in a move that Ludlow describes as arbitrary and capricious, E.A. terminated Urizenus' "Sims Online" account. "While we regret it," E.A. told him in a letter, "we feel it is necessary for the good of the game and its community." Alphaville's Citizen Kane was kicked out of town.

According to Ludlow, E.A.'s move was "clearly censorship," and other scholars of MMORPGS -- massively multiplayer online role playing games, a category that describes the online worlds of "The Sims," "Everquest," "Ultima Online," and new entrants "There" and "Second Life" -- who are familiar with Ludlow's site agree with his assessment. They say the situation underscores what is becoming increasingly apparent in the virtual world: There's a fundamental divergence between the interests of a community (typically high-minded goals like freedom of speech and assembly) and the interests of the corporations that run those communities (typically not very high-minded but otherwise understandable goals like making money and avoiding public association with words like "prostitution").

"[These virtual worlds] are a strange sort of commercial space where communities come to exist, but there's a tension between the communities and the private commercial company," says Julian Dibbell, the author of "My Tiny Life," a kind of memoir about the virtual world LambdaMOO. "It's similar to what you have with shopping malls. They're becoming the last refuge of public space for teenagers, but they're run by companies, and they can kick you out on a whim."

The story also prompts a host of compelling questions regarding the nature of virtual existence. For instance, can something like prostitution occur online? And what about community-based policing -- is that possible, or desirable, in the Sim world? And, finally, does E.A. have any obligation to allow a free press to document how all these issues will play out in "The Sims Online"? After all, it's their world -- why can't they run it how they please, however capricious their rule may seem to others?

Peter Ludlow's abiding interest in "The Sims Online" is, he says, professional. The question "What emerges from a state of nature?" is an old chestnut among philosophers, and Ludlow figured that by observing a virtual world like "The Sims Online" he could get some pretty good clues pointing to the answer. "You can think of these worlds as being like little laboratories in which you see the ways people respond to troublemakers, how they can be resourceful about it," he says. "I'm pretty sure I'm going to write a book on this whole thing."

It's not clear if they're worthy of a book, but the troublemakers Urizenus has found are, at least, good enough for a blog. At the top of the heap -- "Alphaville's most infamous scammer," Urizenus wrote in the Herald -- is a female avatar named Evangeline, who is, in real life, an adolescent male. Urizenus first encountered Evangeline in November, when he'd heard reports of characters "setting up a welcome house, offering assistance to newbies, and then scamming newbies out of their simoleans." (The simolean is the currency used in "The Sims Online"; it can be exchanged for real American dollars on, among other sites, eBay.) Urizenus set up a sting to catch Evangeline. He gave a newbie 30,000 simoleans and had her "seek help" from Evangeline -- and, sure enough, Evangeline and her roommate, Cari, stole the newbie's money. Evangeline is also famous for "caging" newbies and insulting them (she calls the dark-skinned ones "monkeys").

Urizenus has interviewed Evangeline several times, and in her discussions with him, she seems bemused by her exploits, taking nothing very seriously. Ludlow mostly shares that attitude, but he and Candace Bolter, a philosophy grad student at Michigan who works with him on the Herald, were a bit disturbed by one interview Evangeline did with Urizenus in which she describes running a brothel.

In "The Sims Online," prostitution is, necessarily, an occupation that is more of the mind than of the flesh. "Sex" in this world consists mostly of dirty talk. "It basically involves typing to each other in descriptive ways -- typing with one hand, let's put it that way," Ludlow says. Evangeline told him that she would pleasure other characters that way, and they would give her simoleans in return -- sometimes as much as 500,000 simoleans, which at the time was more than $50. (Due to massive inflation in Alphaville, the value of the simolean has since plunged.)

What bothered Ludlow and Bolter about this was that Evangeline asserted that, in real life, he was a minor and that many of the "girls" he hired to talk dirty in his brothel were also underage. Bolter wondered whether the characters were breaking any laws or doing anything else immoral or unethical. She says she acknowledges that, because the characters weren't having real sex, it's hard to say they were involved in "prostitution."

"Some people say, 'Hey, this is virtual reality, it's not an actual thing, it doesn't matter,'" she says. "But if you can show that real money is involved it's an interesting situation. And I think it can be exploitative -- it concerns me that there is real money involved, and I'm also sympathetic to the idea that it could be an issue of [objectionable] content even if it's not prostitution."

The laws in this area are gray; none of the academics who study these worlds could say, definitively, whether the game company or the characters were involved in anything illegal or even really dangerous. Kids on AOL are free to -- and often do -- chat dirty all the time. Is it really so bad if kids on "The Sims Online" do the same thing for virtual money? But experts agreed that this is the sort of issue that game firms should think seriously about. "I do know it's a maxim in the game industry that when a game is boring and there's nothing else to do people turn to sex," noted Edward Castronova, an economist at Cal State Fullerton who studies (and plays in) online worlds.

In response to characters like Evangeline, a group of players in Alphaville joined together to form what they call the Sim Shadow Government -- a development that some players have welcomed, but that others can't stand. Members of the SSG, as they're known, seem like they want to rain on other people's parades.

"In my opinion I don't think the game was designed for people to become 'scammers' and to harm other Sims," Snow White, the group's leader, told Urizenus. "It is more of a glorified chatroom, to be friendly with others, not to betray them." The SSG has had some success in curbing misbehavior, but their efforts are limited by the physics of the game, and they've done little to stop Evangeline, Ludlow says. Still, Ludlow regards the SSG as a clue to his philosophical queries. What emerges from the state of nature? "It's not a single noble monarch," he says. "It's the Sim Shadow Government" -- a weak, minimally effective, but perhaps necessary force.

Early in November, a character came up to Urizenus in Alphaville and, quite suddenly, "became confessional," Ludlow says. The character told Ludlow that he was a teenage boy and that he had been beating up his sister -- that he "sent her to the hospital," in fact. Ludlow didn't know if the account was true, and he had no way of knowing who the character was in real life and where he or she lived, but he found the story alarming enough to report it to Maxis, asking the company to alert local authorities. But the response he got back from the firm did not address his plea, and instead the company told him to ignore any character who offended him. Over the course of a few weeks, Ludlow and Bolter sent the company several follow-up requests to intervene, but they did nothing.

Finally, early in December, Bolter sent a heated letter to E.A., a letter she also posted online under the heading "E.A.'s Indifference on Record Here & Now." "Quite frankly," Bolter wrote, "this is a very serious issue and your lack of response is not only exasperating but also sickeningly disturbing. I literally lose sleep over this issue, yet everyone at E.A. must be sleeping so well (on comfy beds from the money your customers provide to you, it might be noted) that no one can even bother to reply to my inquiry. I'm imploring you to take the time to explain your rationale to me now. The customer is indeed not always right, but doesn't she at least deserve a reply to a legitimate inquiry?"

Bolter's tactic worked. "In response to concerns raised by a petitioner, and after careful review of our Web log, we contacted local authorities and identified the player," the firm said in a letter to her. "Resolution of his incident now lies with the local authorities."

It was the very next day that Ludlow got a letter from E.A. about his site. On Dec. 6, the company warned him that his link to alphavilleherald.com in his Sims profile violated the firm's policy prohibiting links to commercial sites. Ludlow maintains that the Herald is not a commercial entity -- which is a dubious proposition, since it does run ads for in-game virtual businesses such as Mephisto's Goth Supplies ("Need that special gargoyle or head in a jar to make your living room just right?") -- and he says that many Sims players link to all kinds of sites all over the Web, but he acceded to E.A.'s demand and took down the link. Yet on Wednesday, E.A. sent him another letter saying he was still violating the policy and that the company was suspending his account for three days. And then, about 11 hours later, E.A. sent him the final letter terminating his account. (Electronic Arts could not be reached for comment.)

Ludlow has no evidence that E.A. ever read his site, but he thinks the timing is suspicious. Julian Dibbell says he sees the case as censorship; he doubts that there would be any legitimate reason to dismiss Ludlow from the game. "I have a hard time picturing Peter Ludlow engaged in griefing" -- a term applied to people who do nothing but create trouble online -- "or exploiting or any of the standard breaches of good game behavior."

But even if Ludlow was censored, is that wrong? Ludlow says so. He just completed reading a biography of Benjamin Franklin, and "the Pennsylvania Colony, at the time, was basically the possession of the Penn family. Franklin had the temerity to say to them, 'It's not your world.' And a question is going to begin to arise in some of these worlds about exactly how arbitrary and capricious game owners can be just because they're maintaining the infrastructure for a virtual community."

Several other games have fan sites or newspapers that cover them, but experts could recall no other instance of clear-cut censorship. Some worlds have even encouraged journalism. "Second Life" has "embedded" Wagner James Au (a frequent Salon contributor) in its world; Au, who is paid by Linden Lab, "Second Life's" creator, has written some fascinating reports of life in "Second Life" on a blog called Notes from a New World.

Au says he is completely free to write what he wants about Second Life -- he's written several pieces critical of the company. But he acknowledges he's in an awkward position. "I'm like the editor in chief of a small town newspaper in a company town," he says of his status. "I'm going to be immersed in the worldview of that company. But most of my writing is that there's some fascinating stuff happening in that world."

Shares