Photo spreads of supersized weapons, sidebars of eye-popping stats, and prose of pumped-up power: What is happening to popular science magazines? It's not quite hardcore, like the descriptions of raw, sweaty military ops in Soldier of Fortune or the Marines' in-house organ, Leatherneck. The science magazines have more of a soft-core vibe. Over the last several years, several have turned themselves into military versions of a Victoria's Secrets catalog.

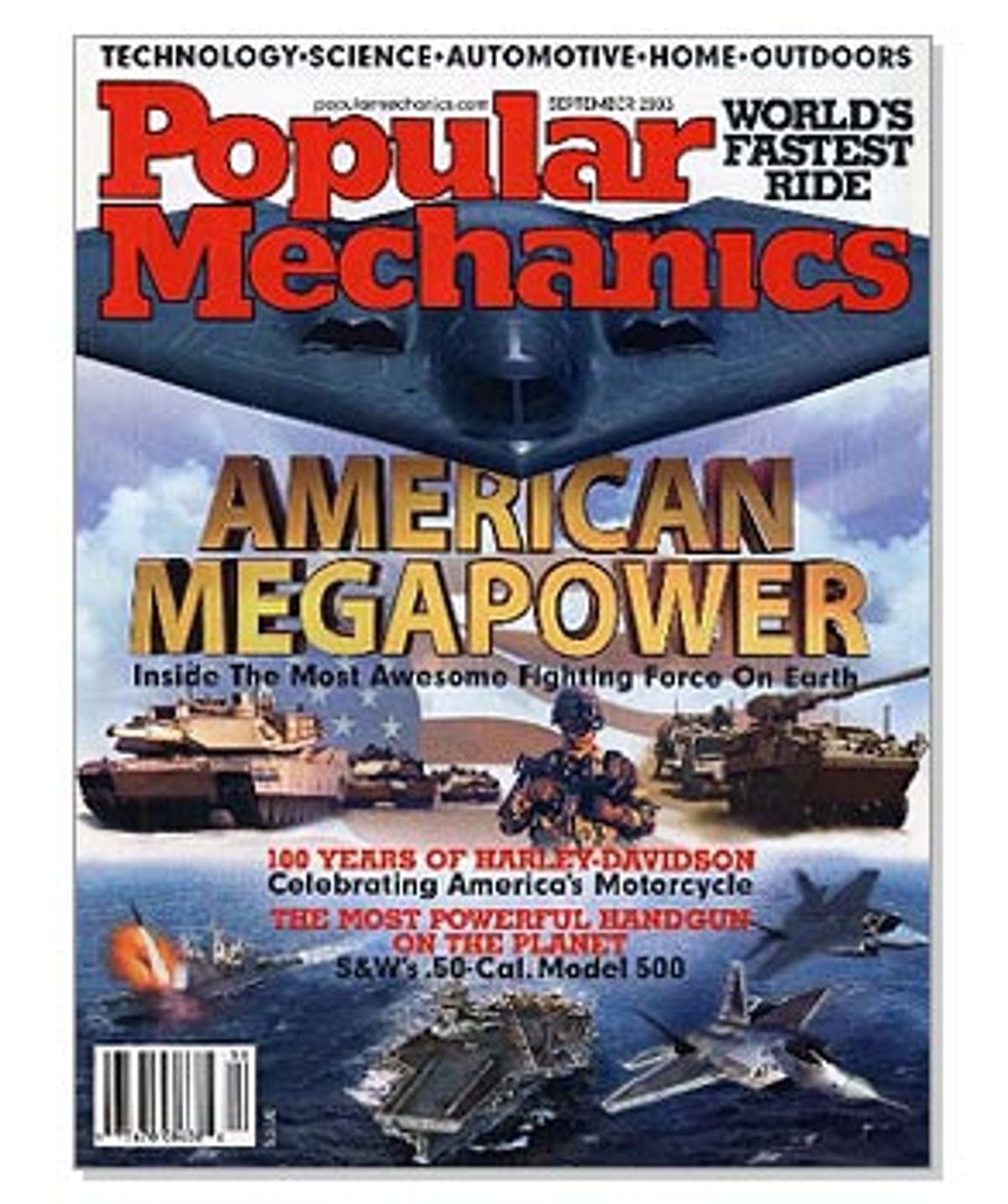

Take the September 2003 issue of Popular Mechanics. The cover proclaims "American Megapower: Inside the Most Awesome Fighting Force on Earth." A bat-winged stealth bomber presides over a group shot of tanks, an aircraft carrier and a visored soldier. The text inside amounts to an unabashed love letter to the Pentagon. No mention is made of how this megapower appears to be bogged down in Iraq or that there are any limits to military force, scientific or otherwise.

The megapower issue was only one of five cover stories that Popular Mechanics ran on the U.S. military in 2003, each one announced with all the subtlety of a tabloid ("Floating Self-Propelled Military Base Projects American Power Anywhere!"). Nearly every month last year featured a new celebration of the military's know-how or sheer force.

Since 2001, the military has become hip: the ultimate extreme sport with all the coolest gear. The military budget is up, the United States launched the war on terrorism and invaded Iraq, and the Pentagon has launched a "hearts and minds" campaign in American popular culture. As a result, military coverage in science magazines has proliferated faster than weapons of mass destruction, particularly in Popular Mechanics and Popular Science.

While Popular Mechanics caters to an almost exclusively male audience -- which explains all the scantily clad babes reclining on speedboats and straddling motorcycles -- Popular Science has traditionally gone after a more diverse demographic. But PopSci, too, has recently been sexed up. In 2003, it featured four cover stories and 10 substantial articles on military affairs, with carefully posed photos of voluptuous stealth bombers, knockout Scud-busters, and alluring autonomous underwater vehicles. In November and December it upped the ante with a pair of full-color military pullouts, concealed behind two-page recruiting ads for the U.S. military. In December, there was a loving comparison between the HMS Victory (of "Master and Commander" vintage) and the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier. November's pullout was something halfway between satire and paranoia: an air-war scenario pitting U.S. federal forces and those of breakaway California 40 years in the future.

Other science magazines cover the military. But they're more sober, less repetitive and considerably less titillating. Popular Science and Popular Mechanics "have a long tradition of covering science and technology as it comes out of the military because they are essentially gee-whiz magazines and all the gee-whiz stuff came out of the military," says Steve Petranek, editor in chief of Discover.

While PopSci and P.M. have long focused on making a direct appeal to the Y chromosome, they weren't always dripping with quite so much testosterone as today. Through the 1970s, such magazines patrolled the borderline between geek and cool, with obligatory issues devoted to cars, house repairs, the emerging computer and robotics fields, and every so often a report on the latest bomber design out of the Pentagon. Even during the Defense Department's last boom-boom era in the 1980s, these magazines remained relatively restrained.

By the early 1990s, Popular Science was running articles on disarmament, cleaning up chemical weapons, and decommissioning the reactors that produced material for America's nuclear weapons. With the Cold War over, the editors began greening the magazine with articles on saving this or that piece of the earth. Even 1991, with the lead-up to the first Gulf War and its aftermath, generated only two covers and three military-related articles. Military articles in the 1990s, instead of gushing, were just as likely to wax nostalgic about old Cold War satellites or serve forth a critique such as a March 1993 investigative piece on the Pentagon's Black Budget. (Popular Mechanics, by contrast, devoted seven cover stories to the military in 1991; although coverage subsided again until the next peak after 2001, the magazine never seemed to return comfortably to its former civilian life.)

In 2000, the Bush team campaigned against the perceived Democratic weakness on military issues. It was only after Sept. 11, however, that the wet dream of the far right -- a $400 billion defense budget -- became a reality. Money was now available for a full range of cutting-edge military hardware, from the terrestrial (self-guiding vehicles) to the empyrean (a new generation of space weapons) to the downright taboo (tactical nukes like the "bunker buster"). Even as it shed manufacturing jobs and lost its competitive edge in key civilian technologies, the United States still boasted a military sector without parallel. Says Joel Johnson, vice president of Aerospace Industries Association, "Given what we spend on Department of Defense R&D and procurement, if we didn't have a comparative advantage on weapons systems, the people in my industry should be taken out and shot."

This comparative advantage translated into more stuff to write about. "It's one of these 'follow the money' things," relates Susan Hassler, editor in chief of Spectrum, the flagship publication of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. "When the military budget goes up, there's more coverage."

But it wasn't simply a question of money. After the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, the Pentagon changed its attitude toward the media. "We get press releases that I never would have gotten before Sept. 11," says Discover's Petranek. "There's clearly an attempt to get out the word from the Pentagon that they're serious about what they do. In some sense, it's kind of refreshing. Historically it's been difficult to report on what the military is doing. There's been a sea change in their attitude."

The Pentagon's new P.R. spin can be found in the unprecedented cooperation extended to Jerry Bruckheimer to produce the TV show "Profiles From the Frontline," about a special-ops unit in Central Asia. Cooperation has its price. In describing its relationship with the TV show "JAG," a Pentagon official told the New York Times, "We offer our assistance when we think it is in the best interest of the Department of Defense and our people, and it's up to the production company to accept it. If they go on and say, 'Thanks but no thanks, we won't make our character be what you stand for,' we are less inclined to support them."

William Hartung, author of the recent book "How Much Are You Making on the War, Daddy?" maintains that the Pentagon is much more conscious in its outreach to popular culture venues. "It wants to give the impression that it's a new, improved Pentagon," he argues. "They have all this futuristic weaponry in the works -- like this cyber-soldier of the future who's basically a networked army of one -- and they want to hide the fact that they're still building all these Cold War weapons that they never took out of the budget. Rifles that see around corners, new space weapons -- it's what Buck Rogers was to a previous generation. It appeals to readers of science magazines, people who are addicted to gadgetry."

In the wake of Sept. 11 and a decision by its owner, Time4, to reorient the magazine toward young men, Popular Science created a new position for an aviation and military editor. In this position, Eric Adams has presided over an expansion of military coverage that takes its cue from the overwhelming popularity of military cover stories among its readership. "The fact that we've had the war and the post-9/11 increased visibility of the military warrants the additional coverage," he explains. "We try not to be gung ho about it. We try not to be particularly negative about it. This is technology that can ostensibly help minimize the impact of war -- the civilian casualties and the losses on our side."

While certainly more on the gung-ho side, Popular Mechanics is nevertheless very detailed in its coverage. Jim Wilson, science editor at P.M. and author of "Combat: The Great American War Planes," relies on expert writers from specialized magazines who often report from a first-person perspective. Other magazines have borrowed P.M.'s style (and, in the case of PopSci, some of P.M.'s editors). In many ways, P.M. set the standard of embeddedness that the Pentagon applied to other media over the last two years.

Being down in the trenches with the military lends a great deal of authenticity and immediacy to P.M.'s coverage. Lacking, however, is critical distance or a willingness to explore the negative consequences of military technology. This is what Susan Hassler of Spectrum describes as a "curious disconnect in popular culture" between, for instance, marveling at the Baghdad sky lit up from the bombing raids of 2003 and ignoring the effects of the bombing on the ground. This disconnect, more than the airbrushed photos or the unveiling of previously secret weapons programs, makes the treatment of military issues by popular science magazines pornographic. Stripped of its moral and political context, the technology is merely mechanical.

Public enthusiasm for war has already seemed to peak. In 2004, U.S. casualties continue to mount, Congress has threatened to trim the president's military budget request, and the Pentagon is just not as sexy as it was back in the blitzkrieg days last spring. And, indeed, the April 2004 issues of PopSci and P.M. have no articles on the military. Nor are there any Army recruitment ads. Instead, attractive couples pitch Viagra, Cialis, Testostazine, and Sildenaflex -- to remind us, perhaps, that popular science is always at the ready to bolster the power and aid the conquests of men.

Shares