If you have paid any attention to the Democratic Party leaders this season, you will have noticed that old-fashioned class populism is back in style. Not only did John Kerry choose the explicitly populist John Edwards as his running mate, but none other than Bill Clinton opened the Democratic National Convention with one of the most strident and successful "people vs. the powerful" speeches in recent convention history. Class-inspired populism may again be on the rise, but if the recent Internet brushfire set off by the irreverent animators at JibJab has anything to say about our culture, the Democrats have a long way to go to make it stick.

In a form as new as Dean scream remixes and eBay bridal gowns, "This Land," by JibJab, has become a nationwide phenomenon. Parents are e-mailing their kids about it; office workers are gathering in guilty half-circles about their cubicles to see it; and its creators, the Spiridellis brothers, have appeared on both Fox News and "The Tonight Show" to promote it. This thing clearly has cachet. The key question is why.

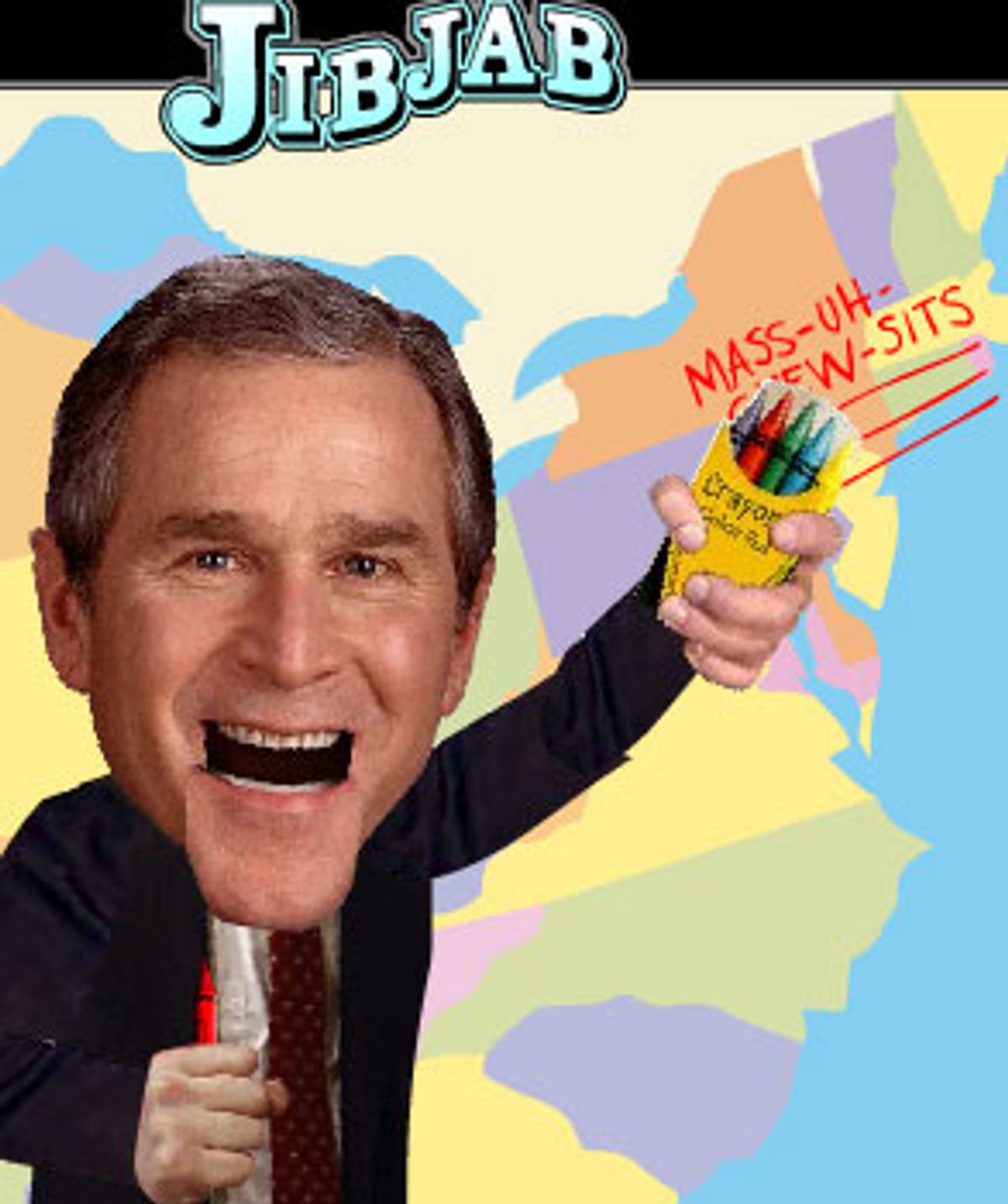

If you haven't seen the piece, you should. It is not exactly PC or even PG, so be warned. In "This Land," Bush and Kerry face off in a clever name-calling fest in which, among other things, Bush proclaims himself to be a "right-wing nutjob" and Kerry appears in S/M garb at the feet of Kofi Annan, Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schroeder. One might think that what sells the piece is its balanced appeal to the riven 50-50 political culture of contemporary America; the Spiridellis brothers take no prisoners, portraying both candidates as fakes and fools. Nevertheless, it's not the equal opportunity character assassination that makes it work. "This Land" has its Warhol moment because it successfully navigates the abiding contradictions of contemporary class populism -- the most salient tension in American political culture.

In the good old days, when you said someone was a populist, that someone was a figure like "the Great Commoner," William Jennings Bryan. Bryan was a Nebraskan lawyer whose great accomplishment was to bring the fiery rhetoric of the Populist Party into the Democratic mainstream. Bryan consistently fought for the little guy but he also fought against urban intellectuals like Clarence Darrow in the so-called Scopes monkey trial of 1925. Bryan wasn't stupid, but he was no intellectual. In these good old days, fighting for the little guy and fighting against the highfalutin went hand in hand.

Recent students of populism like Thomas Frank, Michael Kazin and Terry Bimes have shown how these two aspects of old-style populism have slowly parted company over time. After Truman, leaders on the left lost their fighting faith in the electoral promise of class warfare and embraced what Robert Reich has called the politics of reason. As the Democratic Party embraced education as an ideal, the opposition attacked its intellectual elitism. In 1952, the term egghead was coined to describe Adlai Stevenson as he came to deliver a speech in overeducated Madison, Wis., and by 1964 George Wallace was attacking the Democratic establishment as a bunch of pointy-headed intellectuals. By the time Ronald Reagan came to power in 1980, it was possible to promote trickle-down economics as the intellectual core of a right-wing populist movement.

The "This Land" animation shows how this separation of class politics has transitioned into a complete inversion of the original article. John Kerry is shown to proudly claim his land to be the land of mansions and calculus classes, while consigning Bush to the trailer parks and dunce stools. We are encouraged to mock Kerry for being rich and smart and weak, and to mock Bush for being a stupid everyman. The popularity of "This Land" suggests that class politics in the popular imagination is now a matter of smarts vs. substance rather than rich vs. poor.

It is also ironic that, given its inverted class content, in style the piece falls into a genre that I call the new class populism of political commentary. Although this is a hard call, it seems fair to say that "This Land" owes more to Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock than it does to Rush Limbaugh or Bill O'Reilly. Its hard hits promote more laughs than sneers and it substitutes savvy pop cultural references for jingoistic outrage. This combination of "between the eyes" brashness and hypertextual layering marks it as a creature of the left, even though its most devastating images impugn Kerry and place it nearer the right. In form, this is left propaganda whatever its content and it joins the ranks of courageous if sometimes incautious examples of work in the genre of the new class populism.

To get a sense of what makes this new class populism genre distinctive, think of the bitter critique of "Fahrenheit 9/11" by Christopher Hitchens. The new style is populist precisely because it breaks the careful, aesthetic rules of the intellectual establishment in a direct attempt to avoid the liberal egghead critique. These new works are not better than the old, but they are bolder. What makes them distinctive is their unapologetic embrace of the central problematic of class conflict, their abjuration of objectivity and their entertainment value. They promise no obvious solutions.

Democratic leaders may have recently rediscovered the centrality of class populism to the national Democratic agenda, but data from the authoritative National Election Studies at the University of Michigan demonstrate that this theme never faded as a source of popular appeal. Salience data affirm that if the Democratic Party has an enduring message, it has a class populist flavor. The perennial problem of unwarranted economic differentiation has always seemed out of place against the background ideal of American exceptionalism. This generates a permanent tension in American politics. Those talents who wrestle with this tension in an entertaining way have reason to expect ongoing and widespread popular appeal. That is the lesson that the "This Land" animation teaches and what makes it such a joy to watch. We should expect more of its kind.

Shares