Ernest Rogers, retired aerospace engineer and active inventor, is driving along, running routine car tests west of Salt Lake City, when it happens. A car appears behind his and stays in position, close behind. Then the car pulls up alongside and a passenger leans out her window, camera in hand. She shoots a number of photos of Ernie's car, then shoots more as the car pulls forward and slows. Finally, apparently satisfied, the driver accelerates away while the photographer gives Ernie a thumbs up and a big smile.

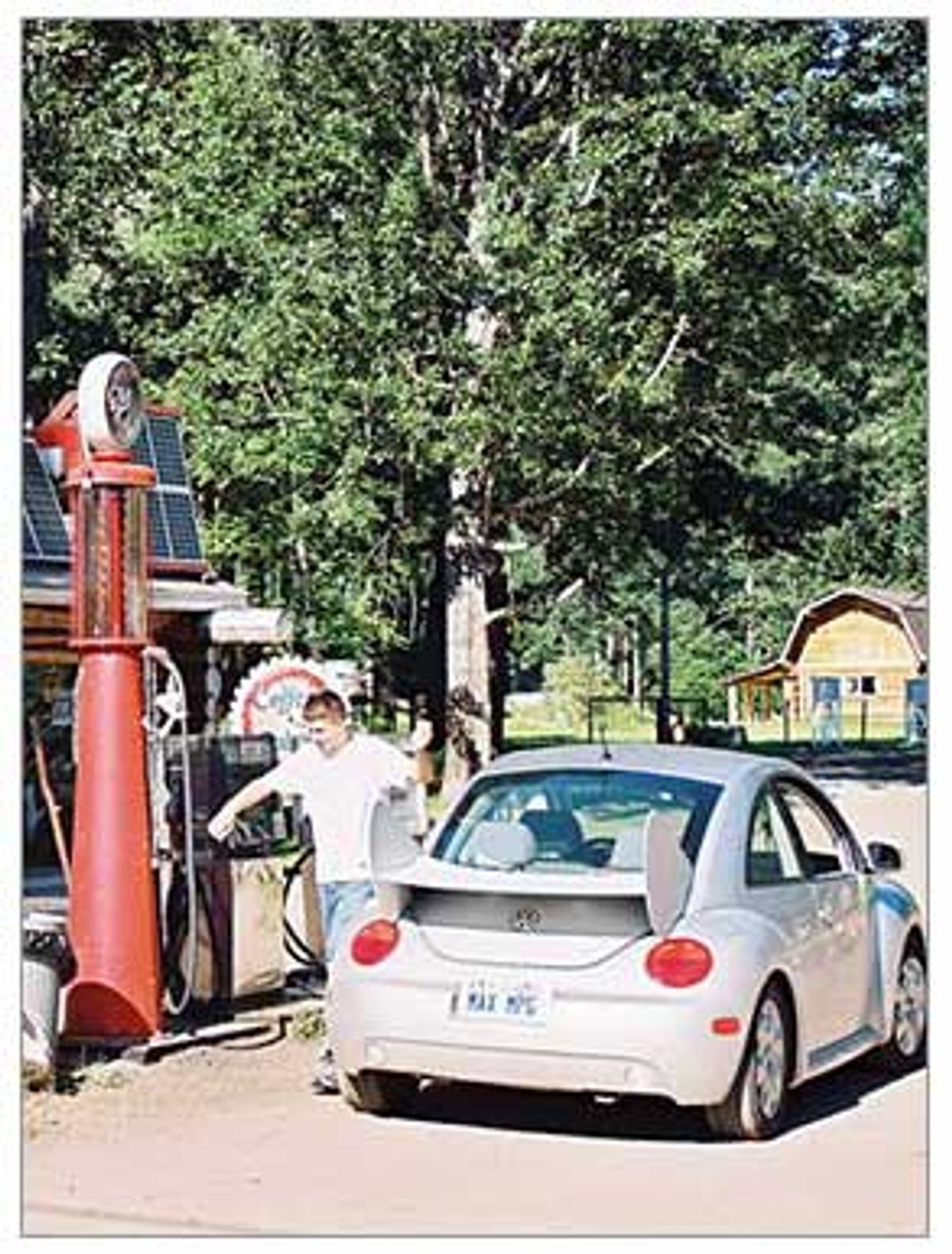

Was Rogers driving some kind of sleek, rocket-boosted dragster or gloriously refurbished classic car? Nope -- his vehicle was something far more relevant to the average consumer -- a new model Volkswagen Beetle, with a twist. This Beetle had a "wing" sticking out the back with two side protrusions. It resembled a silver ladybug. It looked adorable.

Rogers says he likes working on big scientific or engineering problems where he can have a significant effect. Reinventing cars so that they make more efficient use of energy resources is one of those problems.

"The VW Beetle TDI was purchased as an excellent engineering test bed to experiment with because of its inherent high efficiency," says Rogers. "But I couldn't get the best out of this car until I settled a fairly minor problem for it: the fact that its aerodynamic drag is unusually high. I decided to go ahead and fix this problem first because I could see that it has a fairly simple and inexpensive solution. So, the Beetle 'wing' was born."

"I frankly built it for my own selfish use," he says. Then it hit him: Perhaps there was a market for this wing. "Maybe it can start a trend toward making cars that are popular because they are efficient. The Prius [hybrid] has shown that this is a valid concept."

This July, Rogers and his grandson, Kai, drove from their home in Salt Lake City to Anchorage, Alaska, in their VW, with the aerodynamic wing attached to the rear trunk lid. The drive was a success, albeit a slightly more fraught adventure than they had anticipated. They were swept up in the wildfire-driven evacuation of Watson Lake in the Yukon Territory. The conflagrations fueled Rogers' sense of urgency to develop greener energy solutions.

"We drove through about 800 miles of smoke from hundreds of fires burning throughout the western Yukon and eastern Alaska, the result of unusual, very hot and dry spring weather," Rogers wrote in his trip journal. "Everyone up here is talking about the impact of global warming upon the environment."

Rogers, a prolific environmental inventor, has one patent for an oil-water separator for spill cleanups and another for a wind turbine. He once held the position of guest scientist at the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology). He's long been interested in aerodynamic design as a way to increase the fuel efficiency of vehicles.

"I am very concerned with the senseless waste of energy by cars," Rogers wrote in an e-mail. He believes three areas need attention:

- "Power generation and delivery to the wheels"

- "Rolling resistance between the wheels and the road"

- "Aerodynamic resistance between the air and the car"

He continues: "These energy concerns, at the first level, are matters of efficiency. Other views are our expectations on what a 'great car' should do (we all want a great car), the effects of our energy use on ourselves and the rest of the world, and the environmental, social, and economic legacy we will pass on to the future."

While the wing is extremely efficient, it isn't a simple cure-all.

"The Beetle wing only works on the Beetle," Rogers says. "The principles are applicable to all vehicles, but they can look quite different when used elsewhere, for example, on a pickup truck ... In particular, the same drag problem of the Beetle is also present in every big diesel truck. Applying the same concepts there can make a very big impact on our country's energy use."

Indeed, a focus on the trucking industry could have a substantial impact on energy consumption and, consequently, carbon emissions. According to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, more than 2 million semis were in operation in 2001, traveling a combined 135 billion miles on U.S. roads and consuming more than 25 billion gallons of fuel.

It reads like a middle-schooler's math word problem: Most of those 25 billion gallons of fuel were consumed by a small number of trucks that each travel more than 150,000 miles per year. Each of these trucks burns through roughly 35,000 gallons of fuel per year, for a combined total of about 20 billion gallons per year. If there is a 30 percent reduction in drag, which Rogers feels is easily achievable with his wing, the calculated increase in fuel economy is 10 percent, a savings with a value of approximately of $3 billion per year.

This estimate is supported by research by the U.S. Department of Transportation, which has projected that implementing an effective drag reducer at the rear of semis could save at least 1 billion gallons of fuel a year. "We can make cars and trucks that do the same job we have always expected, but with far less fuel," says Rogers. "Let's do it now."

Before he modified his VW, Ernie approached several manufacturers and potential investors to apply a version of his wing to long-haul trucking but was met with little enthusiasm. He was told that this simple design brought up issues too complicated to pursue: loading-dock concerns, manufacturing costs and worries about the wing's durability.

Undeterred by his inability to catch the automotive industry's eye and eager to see if his wing did what he expected, he decided to test the design on his own car. He added his carefully engineered wing to the back trunk lid. It wasn't an expensive design: basically three pieces of material and some bolts.

Before and after comparisons demonstrated an improvement of at least three miles per gallon. But Rogers expected that. What he didn't count on was the public reaction to his modified vehicle.

No one shouted "What sort of mileage are you getting?" as he made his way home, but an awful lot of folks asked him where they could get something like his to make their cars "cute."

"It seems the perception in the accessory marketing business is that the buyer only cares about looks and power, and not about any moral or practical benefit," Rogers says. "Maybe some time soon, 'I look cool' will have a more significant meaning."

When Rogers pulled into a gas station in Pleasant Grove, Utah, after driving 3,000 miles from Anchorage, Alaska, he recalls, "The customer at the adjacent pump came over and asked where he could get a wing like mine. I had to tell him that they just weren't available. He was somewhat disappointed. Then I told him I had just calculated my fuel efficiency at 63 miles per gallon, and watched the behavior that followed. It was entertaining."

What wasn't so entertaining were several anonymous, slur-heavy notes left under the Beetle's windshield wipers, accusing Rogers of tampering with a car-cult favorite. Apparently, even the wing's detractors didn't think there was anything more than "pop car" aesthetics involved.

Rogers' experience driving across the country raises some troubling questions about American attitudes toward conservation. Does the general public simply not take the issue seriously, trusting that there are enough fossil fuels to get them to the mall and back again forever?

"I think a closer guess to reality is that too much of our corporate structure is built on cars that consume lots of fuel," Rogers says. "They are doing all they can to convince us that nobody really wants those 'little' cars. At least until they announce that they have a thrifty car we need to buy ... It's just marketing."

This issue of the straightforward practicality of conservation versus the ability to catch the public with "green" eye candy is clearly illustrated in Rogers' inability to sell the utilitarian use of the wing, while people on the street are stopping him to ask where they can purchase one because of how it adds to the Beetle's funkability.

According to Autobytel, an Internet automotive marketing data source, purchase requests for SUVs and trucks dropped considerably during spring 2004. Requests for the Hummer H2 fell by 47 percent, and those for the Ford Expedition dropped by 25 percent, from first quarter 2004 sales. Still, minivans bucked the downsizing trend and showed an increase in sales, by as much as 67 percent in the case of the Ford Freestar, so while fuel consumption may indeed be an issue, so is roominess.

If the public won't come to conservationism, then conservationism, it seems, will have to come to them, and it will need to arrive in an extremely inviting package.

Shares