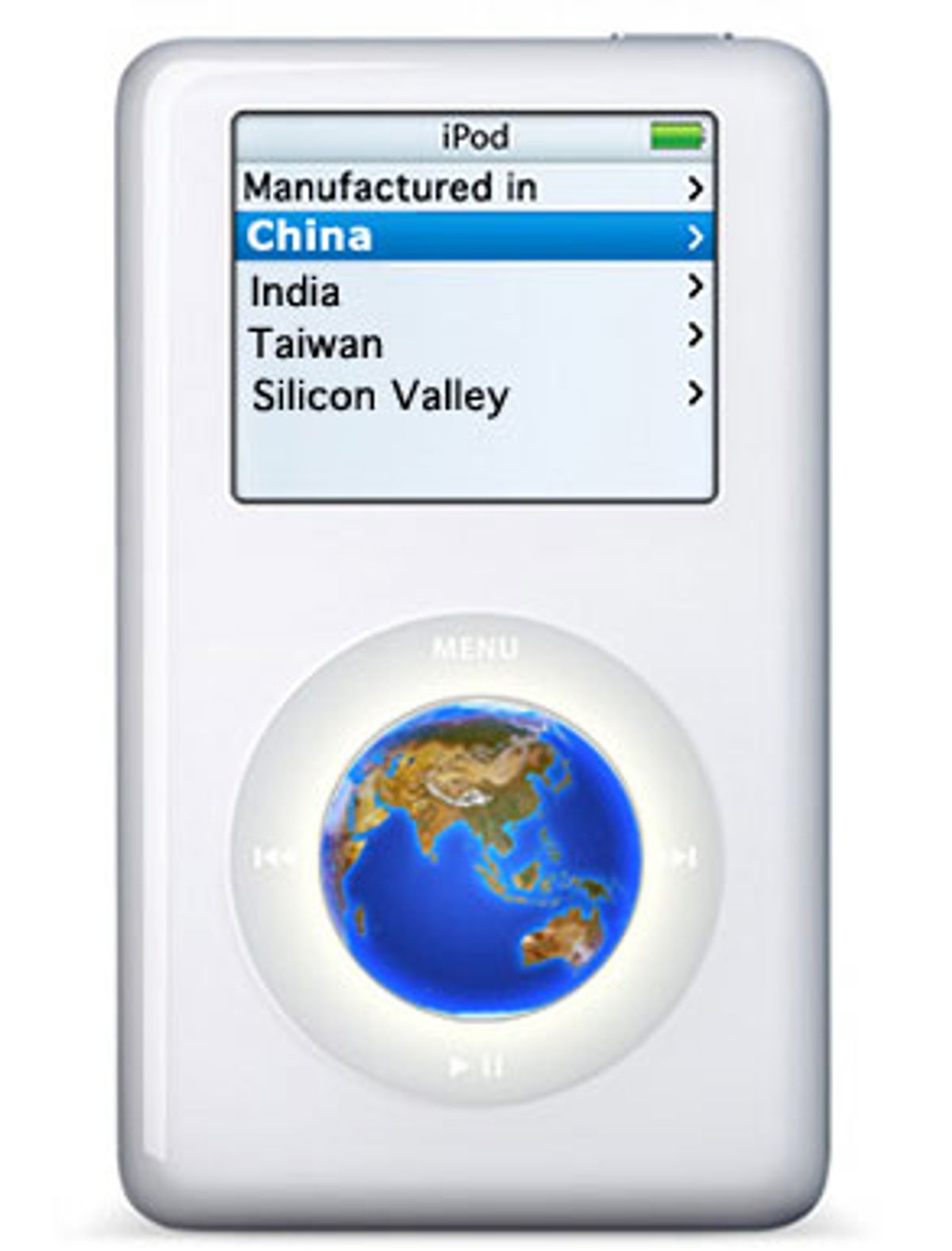

Crack open an iPod and what do you see? Laid out in silicon is a road map for the world economy: globalized, outsourced, offshored, interconnected and complex. Take a look at the components: the hard drive, circuit board, click wheel, battery pack and all the rest. The iPod is a striking Apple success story, but the first thing worth noting is that Apple doesn't "make" it. Steve Jobs and Co. led the overall design, but the pieces get put together in China by a pair of Taiwanese firms.

On its own, this is hardly eyebrow-raising. Consumer electronic manufacturing has been moving to Asia for decades. The Taiwanese companies now setting up shop in China are following exactly the same impulse -- cheaper costs -- as their Western forebears. They aren't alone. Nearly all the other makers of iPod components are also en route to China.

But let's go deeper, into the brains of the iPod, the microchip that makes the music player go. Designed by a Silicon Valley company called PortalPlayer, this "controller" chip offers the real blueprint of how the modern world works. Headquartered in the U.S., PortalPlayer got its chip into one of the world's most coveted consumer electronic devices by outsourcing or subcontracting every possible step of design and manufacturing. By operating around the clock, with teams of engineers across the globe hammering out the chip's hardware design and essential software, PortalPlayer relentlessly delivered new versions of the chip, each one cheaper and faster than the one before, packed with more features but using less power.

PortalPlayer itself is a success. The company is now listed on NASDAQ and turns a profit. But if you visited PortalPlayer's Santa Clara, Calif., headquarters in April, you would have seen, all along one of the city's main thoroughfares, ominously large signs emblazoned with the words "Commercial Lease Available." Santa Clara, it turns out, is suffering a 28 percent commercial real estate vacancy rate, the worst in the Bay Area. Even worse, the San Jose metropolitan area, the heart of Silicon Valley, has lost almost 200,000 jobs in the last four years.

The chip business has not abandoned Silicon Valley. Intel, the industry's king, is still based here, as are scores of other companies involved in semiconductor manufacturing. The world market for semiconductors is growing and the Valley has a big chunk of it. But the jobs and real estates statistics pose an unavoidable question about PortalPlayer's success: Has the rush to outsource high-tech jobs, and maybe more crucially, high-tech expertise, inflicted a body blow on Silicon Valley, and by extension, the U.S. economy?

It's a question fraught with contradictions. PortalPlayer has done nothing wrong; on the contrary, it has done exactly what it is supposed to do, according to the dictates of the market and its responsibilities to its shareholders. But what is the impact of a thousand PortalPlayers, acting together, shifting jobs and technology from the U.S. to locations all over the world?

Critics are worried about trade deficits, job numbers, and even national defense. They are convinced the U.S. has sown the seeds of its own decline by shipping jobs and technological know-how to future superpowers like India and China.

Defenders of Silicon Valley argue just as strenuously that the U.S. will continue to stay at the top of the "value chain." They say that whatever economic blips the Valley's chip industry might be experiencing are just part of an age-old boom-bust cycle. They portray a "golden triangle" new world order in which every nation contributes what it does best -- low-cost development in India, manufacturing in China, high-level design in the U.S. -- and all prosper together.

Who's right? The more closely you examine a microchip, the more complex it appears, and so does any attempt to grapple with the true impact of globalization. But following the journey of PortalPlayer's chip from Santa Clara to Hyderabad, India, to Taipei, Taiwan, to Shanghai, China, and back around again, offers clues on how to think about it.

A few points stand out. Making a buck in high-tech has never been harder and competition will only get more intense. World dynamics are changing and not just because U.S. companies go abroad in search of cheap labor. Along with the strategic decisions of companies, the political actions of nations play important determining roles in who will dominate the crucial industries of the high-tech future.

As Silicon Valley companies seek profit, East Asian nations seek to build up entire industries. While one side outsources, the other side gobbles up. The willingness of U.S. chip companies to move operations to, say, China plays into the hands of China's intention to become a world leader in one of modern economy's most crucial industries.

Open up an iPod and pull out the PortalPlayer chip. Stare at the silicon, see the world.

In 1999, Gordon Campbell, a venture capitalist with a wealth of experience in the chip industry, came to one of Silicon Valley's long-established powerhouses, National Semiconductor, with a suggestion: The company should make a chip targeting the MP3 player market.

The idea was slightly ahead of its time -- Napster had yet to break big and the music industry still hadn't given up its efforts to sue the first entry in the MP3 player field, the Diamond Rio, out of business. National Semiconductor said no thanks.

But according to one published report, National's chief technology officer, John Mallard, followed Campbell out into the parking lot. Soon enough, in time-honored Valley fashion, six National execs jumped ship and formed PortalPlayer. Right into the teeth of the great tech bubble blowout.

Michael Maia, V.P. of marketing for PortalPlayer, laughs out loud when the parking lot story is mentioned, but neither confirms nor denies it. He agrees, though, that starting a new company in late 1999, just before the bottom dropped out of the tech economy, "was an interesting time to be building a business."

So interesting, in fact, that success demanded innovative thinking, not just in chip design, but in business model. On the manufacturing side, PortalPlayer would follow a path well-worn in the Valley for at least a decade or more. It would be a "fabless" design house -- so-called because PortalPlayer would not fabricate its own chips. That job would be outsourced to Taiwan. But PortalPlayer added a tweak: The chip's design, an immensely complex and labor-intensive undertaking involving both hardware layout and software coding, would be split between the U.S. and a fully owned subsidiary in Hyderabad, India.

"From the very beginning, we said we are going to set up a good-sized Indian facility, because the breadth of available resources coming out of India in the software area is huge," says Maia. Three of PortalPlayer's original six founders are of Indian descent.

It's part of the logic of market capitalism that political or national loyalties make little sense in individual companies' Darwinian struggle to make a buck. In Silicon Valley, prospective start-ups that don't include an Indian component in their business plan will get the cold shoulder from venture capitalists. Are you asking not to be taken seriously?

Today, PortalPlayer employs some 194 people. About half of those are in Hyderabad. Another 50 or so are now in San Jose (the company moved its headquarters from Santa Clara in May). Around 30 are in Kirkland, Wash., about 15 minutes from Microsoft and RealNetworks, two central players in the music delivery business.

There are several advantages to this setup. The first is overhead. Indian engineers are cheaper than American engineers but capable of working at just as high a level. What's more, in the ultra-competitive world of both chip design and consumer electronics, the pressure of the business cycle is remorseless. Being late to market with a new version of your product can spell doom. Any number of companies in the Valley, the U.S. or, increasingly, abroad would love Apple's business. (Indeed, the iPod Shuffle, which uses Flash memory instead of a hard drive, runs on a chip from a competing company.) All they need is a slight edge, in price, in power, in features, to make their move.

The competitive pressure has forced PortalPlayer, like many of its colleagues, to work on a 24-hour development cycle. Each morning and evening, PortalPlayer's U.S. developers meet online with their Indian counterparts. Either side can then hand off work-in-progress to the other, check the other's work for errors, or proceed collaboratively. From Hyderabad to Santa Clara, the sun never sets on PortalPlayer.

Success did not come immediately. At one point, the plan was to make a CD recorder; at another, PortalPlayer execs prepared to get into the music delivery business. But in the summer of 2001, PortalPlayer's chip, which reportedly delivered better-sounding music and offered more flexibility than the offerings from nine other competitors, landed the Apple contract. "I'm quite impressed with PortalPlayer," says Shyam Nagrani, an analyst at iSuppli, a firm that tracks developments in the semiconductor industry. "Their products are obviously very good." Ever since, the company's fortunes have followed the iPod. (PortalPlayer refuses to comment on any aspect of its relationship with Apple, and Apple, as a general rule, does not comment on its suppliers.)

Still, even after Apple's blessing, PortalPlayer's road was a little rocky. Mallard left in December 2002 ("to pursue other interests" says Maia), and there were layoffs in early 2003. But the company went public in November 2004, has recorded two consecutive profitable quarters, and total iPod sales are expected to reach 35 million units by the end of 2006.

"Getting to that first million [dollars of revenue] was tough," says Maia, "but each subsequent million is happening at a faster rate."

"When we talk to our customers," says Michael Maia, "what I say is, we're a firmware development house but we also sell semiconductors."

What Maia means is that the value PortalPlayer offers isn't contained primarily in the hardware design of its chips but in the software that the company cooks up to make the best use of the chip's capabilities.

"Firmware" is a fancy term for software that is embedded directly into hardware and generally does not get modified by the end-user. In PortalPlayer's case, the term refers to about a million lines of code, a miniature operating system that carries out all the tasks necessary for a state-of-the-art media player device. Such tasks include audio encoding, digital-rights management, power management, a database for handling thousands of files -- music, photographs and eventually video -- on a tiny hard drive, and hooks for all the other technologies built into the iPod.

Those million lines of code are PortalPlayer's competitive advantage, the intellectual property that makes songs on your iPod sound good and the device easy to use. The code is written by PortalPlayer's developers in Santa Clara and Kirkland, and its fully owned subsidiary in Hyderabad, India. Everything else that can be spun off, is.

PortalPlayer didn't even create the basic structure of its own chip. The first step in the chain is to license a microprocessor chip design from U.K.-based ARM, a company founded in 1990 by Apple and two other firms.

Starting from that ARM template, PortalPlayer's engineers then modify the original layout so that the hardware is optimized for the functions necessary to power a digital media player. This is a complicated, painstaking process. A chip is a piece of silicon with millions of transistors arranged in intricate, interconnecting patterns and layers. As PortalPlayer's engineers revise the original template pattern, the chip must go through a series of verification and testing steps to make sure the modifications work.

But even portions of that task are outsourced. PortalPlayer works with two other Silicon Valley semiconductor design companies, eSilicon and LSI Logic, who help do the nuts and bolts work of translating the design into workable hardware.

Once the final specifications are hammered out and the chip prototype works in the lab, the design is sent to the "wafer fab," a factory that etches discs of silicon with the multilayered patterns.

PortalPlayer relies on two different "foundries," the term for companies that specialize in made-to-order chips. Both are headquartered in Taiwan: the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (TSMC) and United Microelectronics Corp. (UMC). Here is where, Maia says, "the huge money" starts getting spent. Manufacturing chips is a process involving hundreds of steps and extraordinarily expensive machinery. (A state-of-the-art fab costs about $3 billion to set up.)

The fabs end up producing thousands of disc-shaped wafers, each of which is imprinted with hundreds of chips. The wafers then go to yet another tier of companies that specialize in testing and packaging. First the wafers have to be chopped up into individual chips, or "die," and then each chip must be tested to make sure it isn't a dud. Finally, it is coated in plastic and made ready for assembly. PortalPlayer uses two different companies for this part of the process, SiliconWare in Taiwan, and Amkor in Korea.

The finished product is shipped to a warehouse in Hong Kong, and then to an assembly plant in Shanghai where it is plugged into a circuit board and inserted into an iPod. And the last step? That iPod is loaded onto a FedEx jet for shipping to your front door.

And that, in a nutshell, is how a state-of-the-art Silicon Valley fabless design house operates.

But what does it mean?

Up until around the mid-'80s, a typical semiconductor company handled every step in-house, from design to final packaging. Such a company was described as "vertically integrated" -- a one-stop shop for semiconductor manufacturing. It was an industry that began in Silicon Valley.

Vertically integrated semiconductor companies still exist. Santa Clara's Intel, which alone accounts for some 15 percent of chip sales in the world, is the leading example. But in the late '80s, a different model -- the fabless design model -- began to emerge and has been growing ever since.

The internal dynamic of the industry forced the change. Over time, the capital investment necessary to operate a fab simply became too great for any but the most well-heeled to afford. And even then it was risky. Owning your own fab, explains Maia, is great when business is good. But the chip industry is intensely cyclical and when business goes sour, "They weigh on you like granite."

But if you didn't own a fab, how were you going to get your chips made? You couldn't exactly go to one of your competitors and ask them for help. For the fabless design niche to grow, it needed another industry niche to appear in concert. Enter the made-to-order foundry business, pioneered by Morris Chang, the founder of Taiwan's TSMC, initially a joint venture between the Taiwanese government and Philips Electronics.

Chang was born in China and worked at Texas Instruments in the U.S. for 20 years. Then he emigrated to Taiwan, where he figured out that if he focused on manufacturing made-to-order semiconductors for outside customers, he would protect himself from exposure to the market failure of any single customer. At the same time, he could insulate the design houses from the huge capital investment necessary for manufacturing. It was a win-win innovation. Both sides have flourished ever since. The fabless design sector of the chip industry now accounts for 16 percent of the overall semiconductor market and is growing every year.

But stripping wafer fabrication from the traditional structure of a chip company was just the first domino to fall in the chip production cycle. If it made business sense to rely on an outside foundry for chip manufacturing, then the obvious next question was what other portions of the supply chain could be shed?

Next on the chopping block: assembly and testing. What was the point of having your chip manufactured in Taiwan, then shipped to Santa Clara for testing and packaging, and then shipped back to Taiwan or Malaysia or China for final assembly into a CD player or cellphone or fancy toaster? It was obviously more efficient to rely on companies that specialized in the task and were located closer to the point of production.

And so it goes. The evolution of chip manufacturing has relentlessly followed a process clunkily dubbed "vertical disaggregation." One step after another in the supply chain gets spun off to those who can do it more cheaply and efficiently, leaving the companies at the top of the value chain increasingly focused on their core competency. One-stop shops have been replaced by what academics call "cross-national production networks."

The rise of vertically disaggregated, cross-national production networks can be seen as a persuasive demonstration of the free market in action. Individual entities, like PortalPlayer, constantly in search of a competitive advantage, dispense with any task that someone else can do more cheaply or efficiently and focus R&D on the particular job that it does best. The wide, immaculately groomed avenues that connect Silicon Valley's business parks are jammed with hundreds of other companies doing exactly the same thing.

But what happens when you've disaggregated everything. If India can do the design and East Asia handles the manufacturing, what's left for Silicon Valley? Lunches with venture capitalists? Meetings with reporters? Or empty office buildings?

I ask Maia if he's worried about some hungry new design start-up from Shanghai knocking on Apple's door tomorrow with a new generation digital media player chip -- faster, cheaper, more powerful than ever before?

"Oh, we're always worried," he says, laughing. But he's not panicking. He is confident that the Valley will find a way to maintain its leadership. "The innovation and the standards and the leading-edge stuff is still primarily coming out of the U.S.," he says. Maia notes that all the "offshore companies" -- the chip companies based in China and Taiwan and Korea -- want to set up shop in Silicon Valley, "so that they can keep their ear to the action."

By "action," Maia means the cutting edge, the latest innovations in design, the ferment that comes from being the historical center of the world's computer business. "We are here," says Maia. "We are the action. We are creating the action."

Indeed, just a block or two from PortalPlayer, stands Hynix Semiconductor, a Korean manufacturer of memory chips. In the global economy, it makes sense for the world to come to Silicon Valley as much as for the Valley to go to the world.

I ask PortalPlayer India's J.A. Chowdary what is to stop Indian chip designers from working directly with Asian manufacturers, cutting out the Silicon Valley middleman. He soothingly invokes a "golden triangle" of U.S. designers, Indian engineers and Chinese manufacturers, balanced in a mutually beneficial stasis for a good long time. "The design and architecture development is done in the U.S. The development work is done at comparatively lower costs in India and has a huge manpower of skilled technicians. And the manufacturing is done at affordable and cost-effective prices in China. Each country has its own significant part to play, and contributes in a major way, to the successful production and exporting of globally competitive products. This model will continue to grow and will sustain each other."

In a perfect world, that "golden triangle" would be a globalization dream come true. Every country, every region, contributes what it does best, and the tight links and interconnections made possible by global networks allow everything to work smoothly together, without friction. A rising tide of world prosperity raises all boats.

It could happen. The figures on job losses and vacancy rates in Santa Clara don't prove that the Valley is in decline. It's just as likely, notes University of California at Berkeley economist Cynthia Kroll, that the empty offices are a result of overbuilding during the go-go dot-com years as they are of outsourcing. Burned by the excesses of the bubble, the Valley is acting more prudently now.

"It's very hard to disentangle the wave of off-shoring from weakness in the economy," says Greg Linden, a researcher at Berkeley studying the global semiconductor industry.

It's also hard to refute the oft-heard argument in favor of outsourcing that suggests that companies like PortalPlayer would not exist at all if they did not rely heavily on offshoring. In other words, the 80 employees that PortalPlayer has in the United States would not be possible without the 100 in India.

But there are a couple of other factors to consider in the perfect world of the globalized golden triangle. The chip industry is one of the crown jewels of a highly industrialized economy. If outsourcing leads to a critical mass of technology expertise and manufacturing capability migrating to locations outside the United States, the long-term consequences could be severe. So the Pentagon is worried that it won't be able to find local suppliers of chips necessary for next-generation weapons systems. Economists worry about spiraling trade deficits.

An odd, intriguing aspect of globalization is that the decision by the fabless design houses to pursue their individual interests -- cheaper costs -- plays right into the hands of national entities focused on their own strategic imperatives. It is no accident that Taiwan became a leader in bleeding-edge, made-to-order chip manufacturing, or that China looks set to follow in its much smaller neighbor's path. Before Chang started TSMC, he directed a government research institute that targeted strategically important technology development. In both Taiwan and China, the government has encouraged the chip industry with tax breaks, real estate deals, loans and an assortment of other incentives.

That's because government and business leaders in East Asia consider the chip industry not just as a source of economic profits but as a key component of national strength. So while the fabless companies shed what they consider nonessential, East Asia eagerly snaps up everything it can. As a result, "disaggregation" on the one side has led to "reaggregation" on the other. Look at the PortalPlayer chip: manufactured in Taiwan, tested and packaged in Taiwan, Korea or China, and plugged into an iPod in China.

"The supply chain of the market has fundamentally shifted to Asia," says Len Jelinek, an iSuppli analyst.

This shift has some people very worried -- and they are not just out-of-work engineers. They fear that advanced R&D follows the physical location of production. If you are a cutting-edge engineer interested in working with innovative new techniques for chip manufacturing, you will be drawn not to Silicon Valley but to the scores of brand new fabs being built in Asia. So, for example, the foreign-born engineers getting Ph.D.s at Stanford and Berkeley, who used to get jobs in the Valley, will now increasingly go back to their homes where they can work at the top of their field. That is where engineers are being trained to use the newest tools, and that is where further innovations in technology are likely to spring from.

That is also why analysts in Silicon Valley and policymakers in Washington are asking a host of urgent questions. Will state-of-the-art chip design be the next link in the chain to move? What happens when the U.S. military needs a custom-designed new chip but all the facilities capable of manufacturing it are in China? Will the PortalPlayers of the Valley continue to stay one step ahead of their foreign competitors? Or has Silicon Valley midwifed its own successor into being through its eagerness to divest itself of manufacturing and every other "nonessential" job?

As the U.S. trade deficit with China continued to rise in the spring of 2005, along with signs that China's chip industry was surging ahead at a remarkable pace, the questions were being asked with increasing frequency. In April, the Defense Science Board, an advisory group to the Pentagon, released a 118-page report warning that critical semiconductor manufacturing technology was migrating to Asia, and in particular, China. Also in late April, at hearings held before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to evaluate China's high-technology development, speaker after speaker testified to the rapid growth of China's chip-making industry. Meanwhile, venture capitalists in Silicon Valley are making their own move across the Pacific right now, pouring millions of dollars into Chinese chip design start-ups.

Will one of those start-ups end up displacing PortalPlayer? Will the new skyscrapers of Shanghai cast a dark shadow over the office parks of Santa Clara and Mountain View, Milpitas and San Jose? Over the past few years, if you were discussing the challenge of globalization in the Valley, the topic usually was India, with its legions of inexpensive programmers. But today, more likely than not, the country on everybody's mind is the Middle Kingdom.

End of Part 1. Next: China's love affair with the chip

Shares