"At the end of the day, spam bots do NOT have any fucking money."

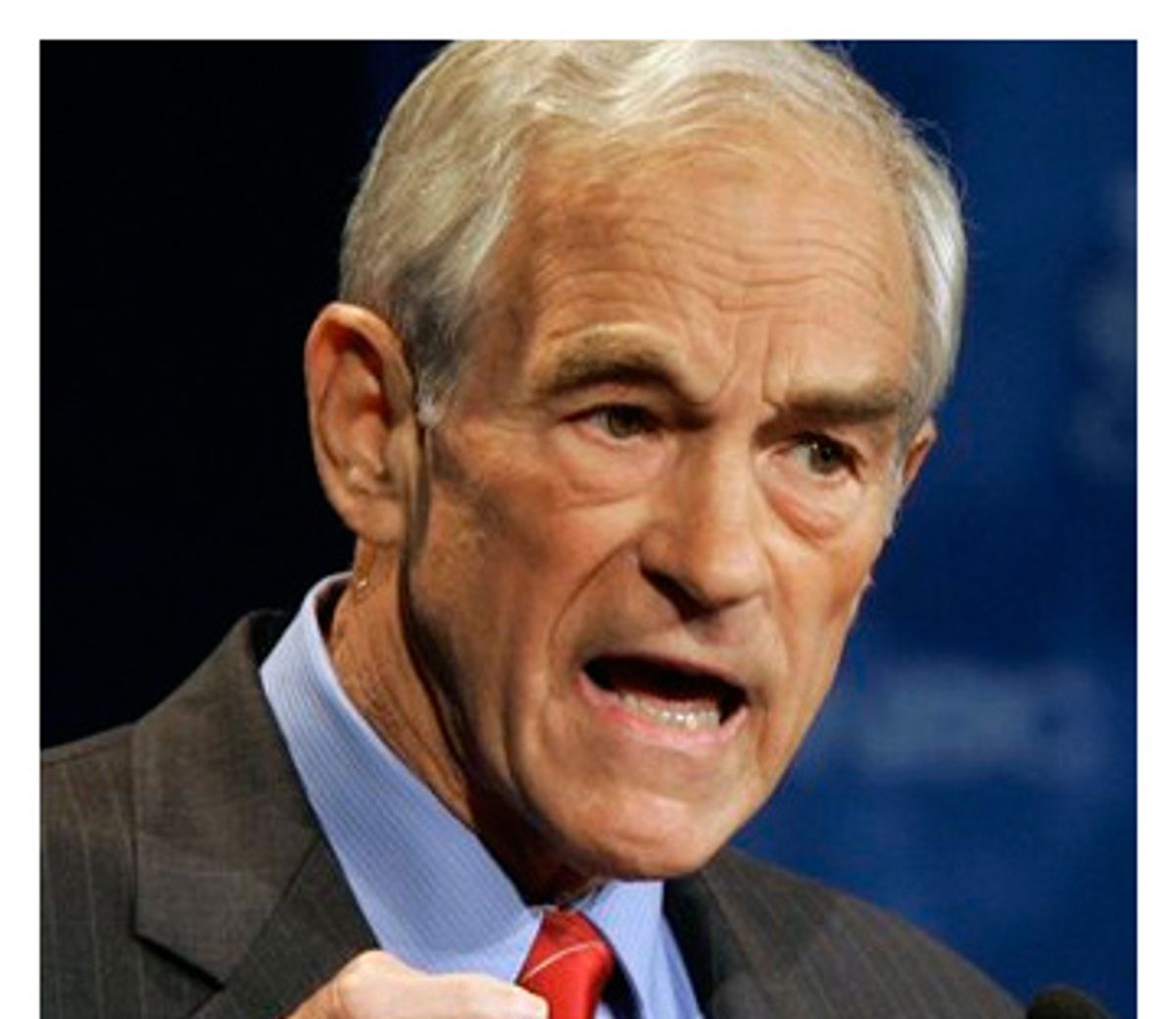

So declared an exulting Ron Paul supporter, in the wake of the candidate's extraordinary online fundraising success on Monday. He was referring to the tempest that roiled the Internet last week, after Wired News reported that some technically savvy Ron Paul supporters appeared to be employing botnets of enslaved computers to gurgitate pro-Ron Paul spam. Big deal! In politics, spam counts for nothing and money changes everything. The latest incredible outpouring of campaign finance contributions ensures, long before a single primary or caucus vote is cast, that Ron Paul will be ignored no longer.

Will it make a damn bit of difference? Howard Dean raised a ton of money and enjoyed a tidal wave of online hype, and then was effectively out of the presidential race before leaving Iowa for New Hampshire. Conventional political wisdom assumes that Paul will follow the same trajectory. Assertions that win or lose, Ron Paul has changed the way the game of politics is played are just that, assertions without much evidence to support them. The only thing that changes politics is getting more votes than everybody else, whether those votes are bought, hacked or delivered by real, live bodies. In American politics, losers don't even get moral victories.

But we won't be counting votes for a while. So in the meantime, you can go visit Ron Paul's campaign Web site and mesmerize yourself by watching the fundraising totals tick upward in real time, as the names of recent contributors flash before your eyes.

And you can wonder, who are these people? Where did they come from? Is this stream of names some kind of roll call for techno-libertarian America? Because that's supposed to be the explanation for all this, right? Geeks skew libertarian, and so the technically savvy swoon for Paul, a one time Libertarian Party candidate for president. From its initial emergence, the Net has always provided a nurturing home for libertarian sympathizers. That equation may have been diluted as the Internet became more mainstream, but the passion still lingers: In a very straightforward way, the Ron Paul campaign represents the revenge of libertarian cyberspace. We have the technology, we can rebuild society! Better, stronger, less government!

So I started Googling. A Guy Averett in Mesa, Ariz., contributed to Ron Paul on Tuesday morning. There's a Guy Averett in Mesa, Ariz., who builds replicas of Star Wars droids as a hobby. It requires some serious work to get geekier than that.

Then there's Max Michaelis, a Texan who has a PDF file of his ideal ultra-minimalist income tax statement posted on his Web site. Michaelis answers his e-mail promptly. He was a little surprised to be called by a reporter less than an hour after contributing some cash to Paul, but, as a mechanical engineer with a long list of computer skills on his résumé, not inordinately so.

Michaelis said he has "always been basically a hard-core libertarian. I was raised on a ranch in Texas and I've always been pro-small government, not happy generally with politics."

"I've liked Ron Paul a long time," said Michaelis, but he'd been doubtful as to his prospects. "I figured he's a cool candidate, but who's gonna vote for him?"

Michaelis said he'd never before contributed to a presidential campaign, but after seeing how much money Paul raked in on Monday, he figured maybe Paul "wasn't a shot in dark."

Michaelis calls himself a "bit of a nerd," but attributed his libertarian beliefs to growing up on a ranch in Texas that "the government has tried to take away several times."

So, scratch the Ron Paul roll call, and sure enough, you don't need to go far to run into a libertarian. And since libertarians have traditionally been more at home on the Internet than most people, it shouldn't be too surprising to see a libertarian candidate enjoying fundraising success, particularly once his campaign started gaining real notoriety. But why? Why do libertarians thrive on the Net?

One Ron Paul supporter told Wired News over the summer that Silicon Valley was going gaga for the Texas Republican because "people in the technology industry tend to be more educated, and more intelligent." Smart people, then, are supposedly natural libertarians. Case closed.

But there may be other reasons.

By the nature of their work, programmers count on being able to precisely manipulate reality through their manipulation of code. When it works, when the computer does as it is told, it is an intoxicating experience, as anyone who has written so much as a "Hello World" script knows. Absolute power! It's the best! And if something goes wrong, it's not because there was something wrong with me, it's because there was something wrong with the code. So tweak it, figure out the correct algorithm, and all ambiguity will be erased, all problems solved.

If only such clarity could be applied to human society! If only we could figure out the right set of rules to maximize freedom and prosperity for all. Libertarians take, as a starting point, that the fewest rules, or the least government, result in the cleanest code and the best results. They look at the messiness that is government as currently practiced and they are horrified and enraged. For many Ron Paul supporters, judging by their voluminous comments all over the Web, the Constitution is the code -- or more precisely, a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution that doesn't allow for its hijacking by busybodies of the left or right. Get back to basics -- get rid of the cruft, the ambiguities, the illogic. Paul's political positions -- antiwar, states' rights, antiabortion, anti-death penalty, abolish the Federal Reserve, go back to the gold standard -- are clear and unambiguous. The code for expressing those views is easily written.

But there is a point at which this analogy does not hold. Because computers don't always do exactly as they are told, especially when they are networked together. Software is buggy, and reality can never be anticipated perfectly enough to capture once and for all in an algorithm. Just ask the hedge fund quants who got burned on Wall Street in August. Software is hard, and so is government. Cruft accumulates.

Which might explain why nothing ever seems to work. And why we are all doomed to messy disappointment.

Shares