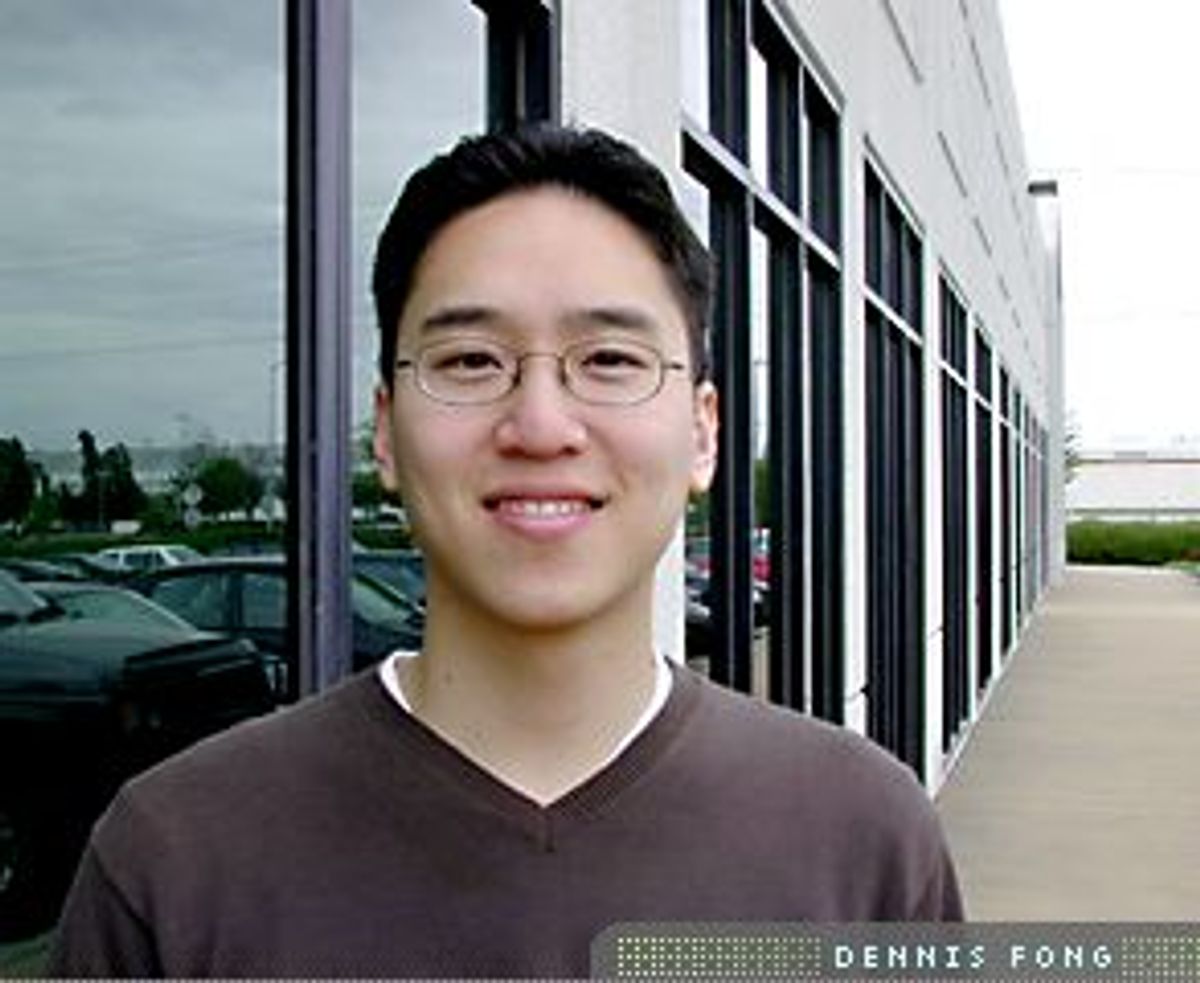

Dennis "Thresh" Fong is the Michael Jordan of electronic gamers. Over the past several years, Fong has proven unbeatable in Doom and Quake tournaments, scoring everything from a Microsoft sponsorship to a Ferrari donated by the co-creator of the games he has mastered. Now the 22-year-old University of California at Berkeley dropout is living up to the Jordan comparison by making the precipitous journey from athlete to entrepreneur.

Since "retiring" from competitions last year, Fong has been devoting himself full-time to Gamers.com, an ambitious portal for gaming fans. With a recent influx of $11.5 million in venture capital, as well as a partnership with AltaVista, Fong is positioning his company to be the gateway for the coming tidal wave of next generation, Internet-ready console players.

To service them, he's built a staff of 150 full-time gamers, hand-picked for their expertise in everything from first-person action shooters to traditional standards like bridge. Each day in their Richmond, Calif., office, the staff aggregates content from across the Net, so that someone coming to the site can get hip to the latest news, patches and gossip in the expanding gaming universe.

"It's one-stop shopping for game players," Fong says. And a potential one-stop gold mine for Fong, especially considering that next generation console makers like Microsoft and Sony are expected to spend over a half-billion dollars to promote their new products.

Fong's journey from digital jock to entrepreneur is a perfect case study of the deep new worlds that have popped up during the rise of Generation Pong. Ten years ago, the thought of a professional gamer would have been absurd. Now, gamers have not only become cultural icons, but industry players. If Fong has his way, he says, "computer and video gaming will become one of the largest sports in the world."

What made you decide to do a portal for gamers?

We saw a need in the industry for something like this. There are literally thousands of Web sites dedicated to games on the Net, but no single, comprehensive source. Take all the online zines. Almost half of them are professionally done. That means they're all competing for exclusive stories. And if one of them gets an exclusive on a game, none of the others will tell their users about it. This results in creating a fragmented community. If you want to be on top of the news every day, there's nowhere to go; you have to surf through a variety of sites.

My brothers and I decided to start Gamers.com back in 1996. We had a huge passion for gaming and believed that it would be a "big deal" down the road. So one night, we logged onto the Internet, registered "gamers.com" for 75 bucks, and off we went. The first two years of our business were essentially a makeshift business school for us -- we made every possible mistake entrepreneurs could make, but it was great because we learned how to be profitable without needing outside funding. It wasn't until two and a half years later that we felt ready to take the next step of raising capital.

Hardcore gamers constitute one of the most idiosyncratic communities on the Net. How can you appeal to them without alienating the mainstream crowd?

Right now, hardcore gamers make up about 2 million of the 150 million people who play games. They're a lot like bikers in biker clubs. If you're not a hardcore gamer, you might be almost as scared of going into one of their communities as you would be visiting a biker club. But really that's just giving in to a stereotype of the gaming community. Many hardcore players don't consider themselves hardcore. Technically, I'm a hardcore player, but I'm not hardcore into video games. Part of what we're trying to do is introduce people who are not really hardcore into gaming. We're trying to make it easy and less fragmented. Instead of surfing around for a site, say, dedicated to Starcraft, you can come here. The gaming community is very tribal; we're trying to get you into the clubs.

What about the niche sites for gamers like Blue's News or ShugaShack, which sprang up from the 3-D action gaming communities?

Blue's News is very detailed; you'll find everything down to news on the latest patch for some obscure game. From a macro level, that's what we do for news. We tell you about all places that are reporting news. If it's Friday night and you want to find out what people think about a game you want to buy, you can come here. Would you rather read one opinion from one critic or get a snapshot of what the whole industry thinks, or what the whole community thinks?

How will the old PC community be affected by the console community coming online?

The next generation consoles [like the Internet-ready Playstation 2 and Microsoft's Xbox] are going to revolutionize the Net. They're Trojan horses into the living room. It's going to be great, bringing in millions of people online. That's good for everyone. New communities will form for console players. And there will be an overlap of communities for consoles and PC players.

Games will be their entree to the Net, so they'll be looking for games content. Part of what we believe is that there will be partnerships with major console manufacturers -- like Sony and Nintendo. It's like when you install Windows 2000, your default browser is Internet Explorer. It'll be the same with games. You'll log on with your Playstation 2 and go to a Playstation 2 page. Having partnerships with them, for us, is key.

You've been called "the Michael Jordan of computer games." Jordan has also become equally well known as an entrepreneur. How do you see yourself evolving as an "athlete-turned-entrepreneur?

I think my life has already evolved from an "athlete" to an entrepreneur. Whether I'm going to be as successful, or lucky, in business as I was in competitive gaming, only time will tell.

I approach Gamers.com in the same way I approach a play. During my competitive gaming, one of my mottoes was "Sometimes you do your best and it doesn't matter, so there's no point in getting nervous." If I played my best and lost that never really bothered me. The other thing was that I always approached competitive gaming like speed chess. Chess is not a strategic game, but you're always thinking fast -- two or three steps ahead of your opponent. You're always placing yourself in the other person's perspective. I got a reputation for doing that so well that people starting calling it "Thresh ESP." But I was just anticipating my opponent's move.

I always put my focus on strategy and tactics; I'd say 70 percent of my energy was on that and the other 30 percent was on skill and precision. I applied that approach to every new game I played: Doom II, Quake, Quake II, Quake III. If I was having a bad day in terms of aim and reflexes, which everyone has, I would just defer to strategy and tactics to squeak out a win. I was always consistent with my style. From a business aspect, it's very applicable. I try to place myself in the user's perspective; it's just another person across the table from me. In that respect, I'm not special. It's just the way my brain's always worked. It's how I'm wired.

How did you get started in electronic gaming?

I was born in Hong Kong in 1977, and didn't move here to California until I was 11. Throughout my life, I've attended American schools, so the move here wasn't a big deal. My dad has worked at Hewlett-Packard for as long as I can remember, and my mom was an English teacher in Hong Kong. I have two brothers, one older, Lyle, and one younger, Bryant. Both of them have always been really into computers, but I was not. In fact, I hated computers and was much more into sports ... until my bros introduced me to Doom. Since that fateful day of playing my first multiplayer game of Doom, I've been hooked. I love to compete, be it in sports, business or gaming. It makes the "game" a lot more fun when there's something on the line.

How did it feel when you realized that you were becoming something of a gaming celebrity?

To this day, I am still very pleasantly surprised when people ask me for my autograph. It's kind of neat and awkward at the same time.

How have you managed to make a living by playing computer games?

In the past, I have been sponsored by companies such as Microsoft and Diamond Multimedia, not unlike how Michael Jordan is sponsored by Nike -- minus the big paycheck. While competing professionally, I also wrote several strategy guides, had a monthly column in a popular gaming magazine and ran Gamers.com at the same time. Oh, and the prize money was always helpful, too ...

Why did you decide to stop competing?

I still play on a regular basis, but haven't had much time to compete in official tournaments. In the past, I'd play an average of an hour a day until two weeks before a tournament, [when] I'd step up my playing time to four to eight hours a day. Now that we've raised $11 million in funding for my company, Gamers.com, it's literally impossible for me to take that much time off work to focus on a tournament. Hopefully I will eventually have enough spare time to compete seriously again.

How has the deathmatching/ LAN-party/tourney scene changed since you first got involved?

The entire gaming scene has evolved tremendously since when I first started. For one, there are a lot more people playing these days. As a result of the masses getting into gaming, that has driven corporate sponsorships of gaming tournaments to a new level, which in turn drives more people to play. Tournaments today regularly feature $100,000-plus prize pools, with the first-place winner taking home approximately $40,000-plus. It's become a very serious sport and I think it's great for the industry. Certainly the more people that get into gaming, the better it is for the industry and the sport.

With the proliferation of big money tournaments comes the not-so-good side as well -- some people feel the fun aspect of gaming is lost since competition has become so fierce.

Shares