After more than five hours of relentlessly hostile grilling from both Democratic and Republican senators, the four former and present Goldman executives appearing on the first panel before the Senate's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations Tuesday were visibly shell-shocked. Fabrice Tourre seemed trapped in a nightmare that wouldn't end. Michael Swensen, a managing director in the structured finance division, looked like he had been sucker-punched. Swensen's former structured finance colleague, Joshua Birnbaum, was still giving as good as he got -- of all the Goldman representatives he was consistently the most nimble in his responses, and even seemed to be enjoy parrying some of the more prosecutorial questioning. But there was flop sweat on his brow, too.

Maybe they'd all been expecting something different, and maybe they could be excused for that, if their expectations were formed by watching other congressional hearings over the last couple of years. Sit and smile through a couple of hours of grandstanding rhetoric from mugging-for-the-cameras senators, say "I don't recall" a few times, and call it a day when the committee moved on to bigger game, like the much anticipated appearance by Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein.

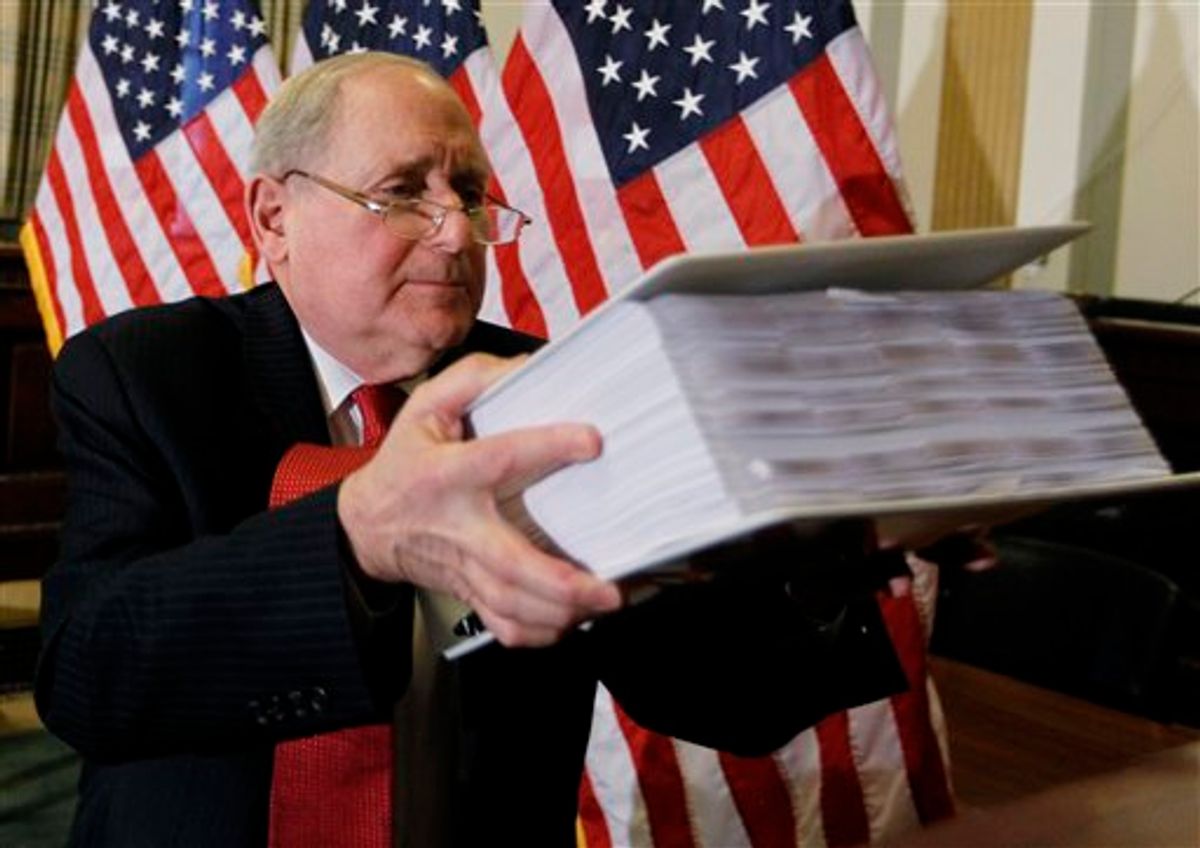

But Sen. Carl Levin is running a different kind of show, something that became obvious when he destroyed Washington Mutual a few weeks ago in the first installment of this sequence of hearings. He came prepared, and so did most of his colleagues, especially Republican Tom Coburn and Democrat Claire McCaskill. Citing e-mail after e-mail in which Goldman employees referred disparagingly to financial products that they were pushing on their clients, the senators kept hammering on a single major point: Even as Goldman started betting against mortgage-backed securities, it was shoveling "junk" at its clients.

The Goldman executives saw no problem with this apparent conflict of interest. Daniel Sparks, Goldman's former head of mortgage finance, was quite explicit: Goldman had no responsibility to tell its clients what kind of position -- long or short -- it might have on the portfolio of investments it was trying to sell to clients. In this respect, he expressed an entirely conventional view on Wall Street.

Sen. Coburn acknowledged that there is a place for a so-called market maker who puts together speculators on both sides of a deal. But Coburn made a crucial distinction. "I want to know," he said, "where's the ethical standard on when you expose your position as the market maker?"

In other words, where do you draw the line? It's one thing to hedge your risk and let the buyer beware. It's another thing to actively and knowingly create bad deals and push them. At some point you stop serving clients and start abusing them, you stop being a mere "intermediary" -- a favorite Goldman locution -- and start behaving as a predator.

For the Goldman execs, Coburn's distinction seemed baffling, almost inconceivable. Goldman executives don't ever seem to have asked each other via e-mail whether their behavior was "ethical." Risky, yes, profitable, of course. But ethical? Such a consideration wasn't a part of Wall Street's framework. The importance of Tuesday's hearing was not in whether or not the senators were able to get Goldman Sachs executives to admit any culpability, but in the force of the assault launched on an entire way of doing business.

Levin and other senators repeatedly asked if the assembled executives felt like they'd done anything wrong, or if they had any regrets. Nope, nothing wrong. Maybe a few mistakes here and there, maybe a few deals that didn't work out as might have been hoped. Maybe the whole industry got a little "loose" on credit. But nothing wrong. And no regrets.

"We did not cause the financial crisis," said Michael Swensen. "I do not think we did anything wrong."

Sen. Jon Tester, D-Mont., asked for advice on how to regulate the system so as not to repeat the experience of the past few years. "What would you change?" But Sparks couldn't even answer that question, other than to say it was "hard." I guess if you feel that you never did anything "wrong," you might have a tough time figuring out what the new rules of the game should be.

No one company caused the financial crisis. But, collectively, a lot of people and companies seeking to maximize their profits without bothering to think whether what they were doing was really good for the country or the economy did cause the financial crisis, and Goldman, as the most successful shark on Wall Street, cannot escape getting part of the blame.

At one point Carl Levin sighed with disgust. He looked directly at Daniel Sparks and said, "You've got no regrets; I think you ought to have plenty of them."

That seems to be a bipartisan point of view.

Shares