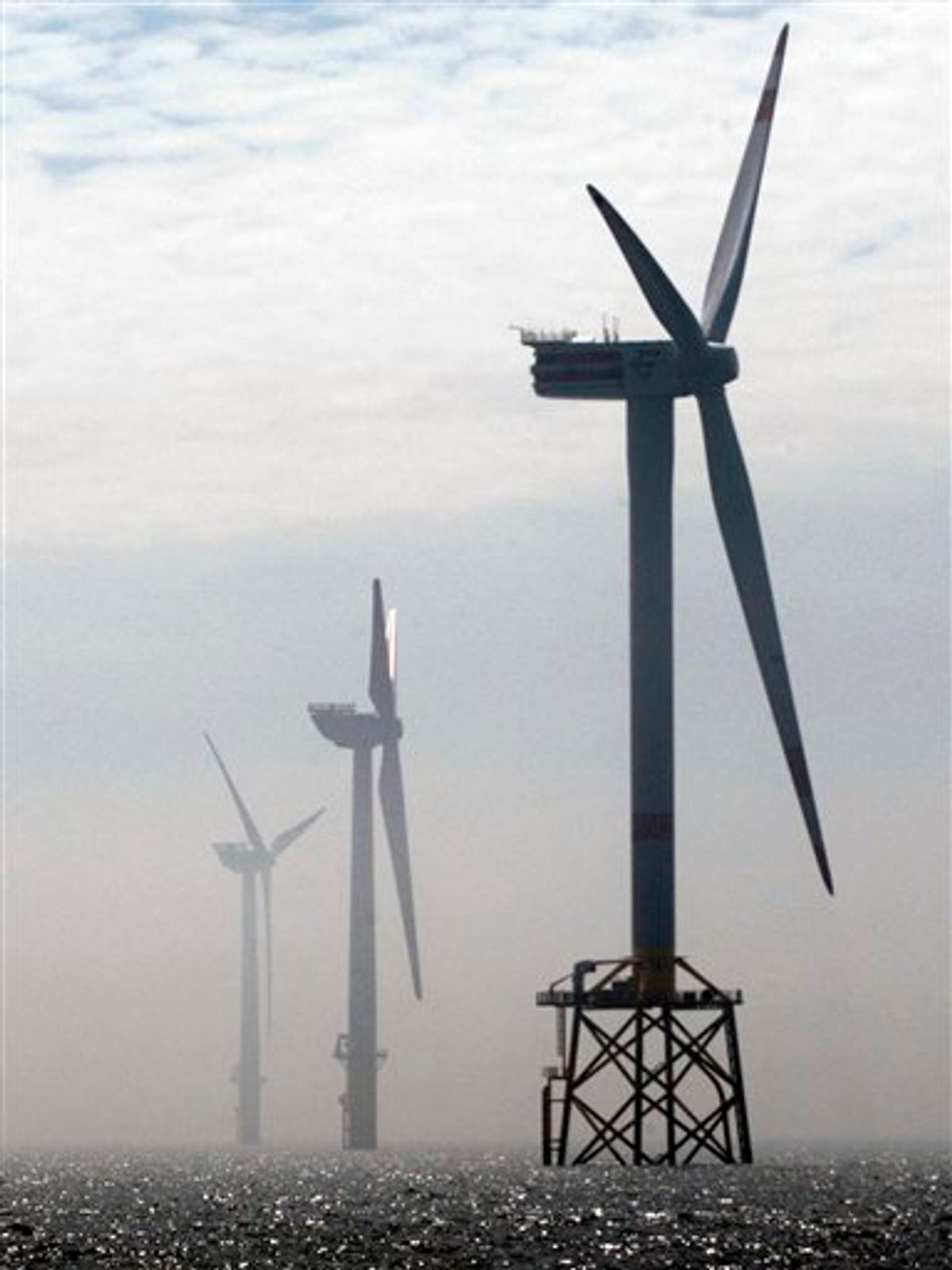

You could not ask for a more drastic demonstration of the contrast between how the United States and China are rolling out renewable energy technologies than the current state of offshore windmill deployment in the two countries.

The U.S. does not have a single offshore windmill currently in operation. The most notorious proposed project in the U.S., the 130-turbine Cape Wind offshore farm planned for Nantucket Sound, has been mired in litigation and politics for almost 10 years. Just this week the Massachusetts Department of Public Works opened hearings investigating whether the terms of the Cape Wind contract would be in the public ratepayer's interest. The hearings will drag on for at least two months, and whatever decision is made will likely be litigated by whichever side loses.

China is a different story altogether. The 102-megawatt Donghai Bridge Wind Farm began operating near Shanghai this July. Four more farms nearby, reports ClimateWire, are under negotiation. And that's just the beginning:

The "Development Plan on Emerging Energies" released July 20 outlines wind production goals through 2020 by the Chinese government.

According to the plan, offshore wind power is expected to reach 30 gigawatts, and coastal provinces were required to start drafting offshore wind-grid implementation plans. This includes Liaoning, Shandong, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong provinces. In the next three to four years, according to the Azure-WWF report, in total, 514 MW should be installed along this coastline. As of March this year, pipelines accommodating 17 MW were already installed between Donghai and a pilot wind project in Bohai Bay near Tianjin.

In China, of course, offshore wind farm developers don't have to worry about the annoyances of environmental impact studies or deep-pocketed neighbors agitated about their ocean views. There are good reasons why it is harder to get a major piece of infrastructure up and running in the United States than in China, and I think I speak for many Americans when I affirm my desire to live in an inefficiently functioning democracy, however frustrating it may be at times, instead of a totalitarian, windmills-run-on-time, proletarian dictatorship.

Plus, there's the added problem that China cheats. In a thoroughly reported Page 1 New York Times article published Wednesday Keith Bradsher makes a pretty good case that China is ramping up its renewable energy sector in part by abusing or simply ignoring international trade rules that are supposed to prevent governments from giving particular industries unfair advantages over international competition. It's so unfair! On one side we have is a cheating, mercantilist, wannabe superpower unrestrained by environmental regulation or civil society, and on the other, a dysfunctional partisan gridlocked mess that can't even get its act together to pass a federal renewable energy electricity standard. No wonder our ass is getting kicked.

The great irony of all this is that the world stands to benefit greatly from China's renewable energy push, regardless of whether it is achieved by fair means or foul. Economies of scale applied to the production of solar panels and wind turbines in China are already pushing prices for renewable energy power down worldwide, making it more and more feasible to replace fossil-fuel power sources with cleantech. Even more encouragingly, the creation of a vast infrastructure for renewable energy research and development is bound to lead to countless downstream technological innovations that lower prices and expand capabilitiies even further.

And that's what the West should really be paying attention to. While progressives complain that China is exploiting cheap labor and ravaging the environment and right-wing nationalists do their best to stir up new Cold War antagonisms, perhaps the most important aspect of the Chinese drive toward a high tech renewable energy future, by any means necessary, is going relatively unnoticed. Slowly but surely, the West is losing its long-held domination of the technological high ground.

An excellent example of this can be found in the domain of rare earth elements, a narrative visited earlier this month in How the World Works here and here. At Carnegie-Mellon University, two professors in the Department of Engineering and Public Policy, Francisco M. Veloso and Cliff Davidson, along with graduate student Brian J. Fifarek, have been conducting research into the impact of the offshoring of rare earth element production upon innovation. Professor Veloso contacted me after reading my earlier posts, having correctly surmised that research into a nexus that connected offshoring, high technology, renewable energy and China would be absolutely irresistible to HTWW.

In "Offshoring technology innovation: A case study of rare-earth technology," published in the Journal of Operations Management in 2008, and "Offshoring and the Global Geography of Innovation," published in the Journal of Economic Geography earlier this year (and available in draft form here,) the authors confirm, by investigating changes in the geographic location of rare earth element technology patent filings, what some might find intuitively obvious: When research and development migrates from one country to another, so does innovation.

Rare earth element (REE) magnet technology -- which, incidentally, is crucial to wind turbine manufacturing -- offers a perfect natural experiment in which to investigate the effect of the offshoring of research and development. First, rare earth elements are critical to a number of important, fast evolving high tech industries so there is a great deal of patent activity. Second, REE magnet technology offshoring started relatively early but progressed quickly and comprehensively. In just 20 years, for example, the United States has gone from a position of leadership to the point of having zero domestic production capability.

The REE industry was an early adopter of offshoring practices, beginning in the 1990s, that affected the whole system involved in rare-earth technology innovation. In fact, the industry is among those that have evolved the furthest on this new path towards outsourcing and relocation away from the U.S. and towards developing countries. This creates an excellent setting to study the potential longer term impacts of offshoring on innovation, especially in the home country.

The pattern goes roughly like this. U.S. firms looking to cut costs start sourcing raw materials from the cheapest supplier -- namely China. Next step, processing the raw ore close to the source of supply, also for cost reasons. Third step: moving research and development into the downstream production of advanced products, such as magnets, closer to the processing facilities. The end result: The locus of new innovation in magnet technology starts to cluster near the processing and production facilities, as proved by an increasing number of rare earth element patent filings generated in Asia as opposed to the U.S.

Rare earth element magnet technology offers a case study in how individual decisions by freely acting firms can end up gutting an entire domestic industry.

As firms seek to position themselves in locations that maximize their efficiency and competitiveness, their decisions will be affected by the changing nature of the systems of innovation, industrial clusters and industrial ecology to which they are exposed. Unfortunately many firms participating in offshoring to increase their individual competitiveness are unwittingly responsible for changes in the system or ecology to which they belong.

...Informal conversations with one firm representative revealed that removing manufacturing from the U.S. has also led to the removal of over 90 percent of domestic R&D activities on rare-earth permanent magnet materials. More importantly, the knowledge for producing [neodymium boron] NdFeB magnets within the U.S. has been lost. U.S.-based manufacturers can no longer compete with the quality of NdFeB magnets produced in China or Japan.

The authors caution that the pattern observed in rare earth element magnets is not an ironclad rule that applies to every high tech industry in which offshoring occurs. And they warn that protectionist polices aimed at preventing offshoring are no silver bullet, as any attempt to build higher walls between the U.S. and its trading powers will likely reduce the global competitiveness of U.S. firms and potentially harm consumers with higher prices for things like ... solar panels.

But there is clearly a role for public policy here. We can't, not should we want to, duplicate China's pell-mell, environment-be-damned complete reordering of society. But there are definitely things we could do that would provide incentives for investment in the technologies of the future right here at home. Like, say, a cap-and-trade system or carbon tax that provides an incentive for investment to flow into renewable energy technology, or state and federal standards that mandate a certain percentage of electricity be generated from renewable sources.

The strategic imperative is simply overwhelming. The struggle over energy policy shouldn't be seen as a culture war between environmentalists and free-market fundamentalists. It should be a matter of basic common sense -- do we want to be involved with making the future, or just buy it from China?

Shares