Never mind Tea Party rage at supposed government over-reach or liberal disappointment with Obama's failure to be the second coming of FDR. The quick and dirty explanation for Democratic political travails in 2010 -- including, but not limited to, the thumping delivered by Republicans in the midterm elections -- can be hung on a single economic indicator. In January, the unemployment rate was 9.7 percent. In November: 9.8.

By the close of the year, one could make a fairly persuasive argument that the U.S. economy was actually on the verge of turning the corner. Auto sales rose steadily throughout the second half of the year, exports surged, holiday retail sales numbers solidly beat expectations, and industrial production kept ticking up. U.S. stock market investors appeared confident about the future -- the Dow Jones Industrial Average was 1,000 points higher in December than in January. There were even signs that the labor market had finally started to improve -- new claims for jobless benefits declined consistently throughout November and December. In fact, the very last jobless claims number of the year brought the weekly total down to a level not previously seen since July 2008.

But the unemployment rate refused to budge. And the importance of that single indicator simply can't be overestimated, for the simple reason that it made it impossible for the White House to tell a good story about the economy -- so much so that administration officials in 2010 were terrified to even mention the word "stimulus." Even though most private -- i.e. nonpartisan -- economic forecasters agree that without the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act unemployment would likely be higher today than it currently is, the it-could-have-been-even-worse argument has zero political heft. Obama came in, spent a lot of money, and appeared to get very little for it. Throughout 2010 he suffered the consequences. The slumping economy torpedoed any chances for passing climate legislation, gave Republicans renewed ammunition for opposing tough regulations on Wall Street, and fueled a grass-roots discontent that manifested itself quite pointedly at the ballot box.

Could this political dynamic change in 2011? The White House has already surprised political pundits by orchestrating a lame-duck legislative session that was far more successful in achieving Democratic priorities than anyone expected. How much stronger would Obama's hand be if the economy steadily gained steam in 2011? Confidence begets confidence -- the better the economy appears to be doing, the more risks investors will be willing to accept and the more likely employers will be to expand hiring. Cue the virtuous cycle: Let loose the animal spirits! Vigorous economic growth, at the very least, would profoundly change the political calculus for the crop of Republicans who aspire to the presidency in 2012. The easiest thing to do in the world for a campaigning politician is to bash the incumbent for a bad economy. Without that crutch, one must fall back into swampier waters.

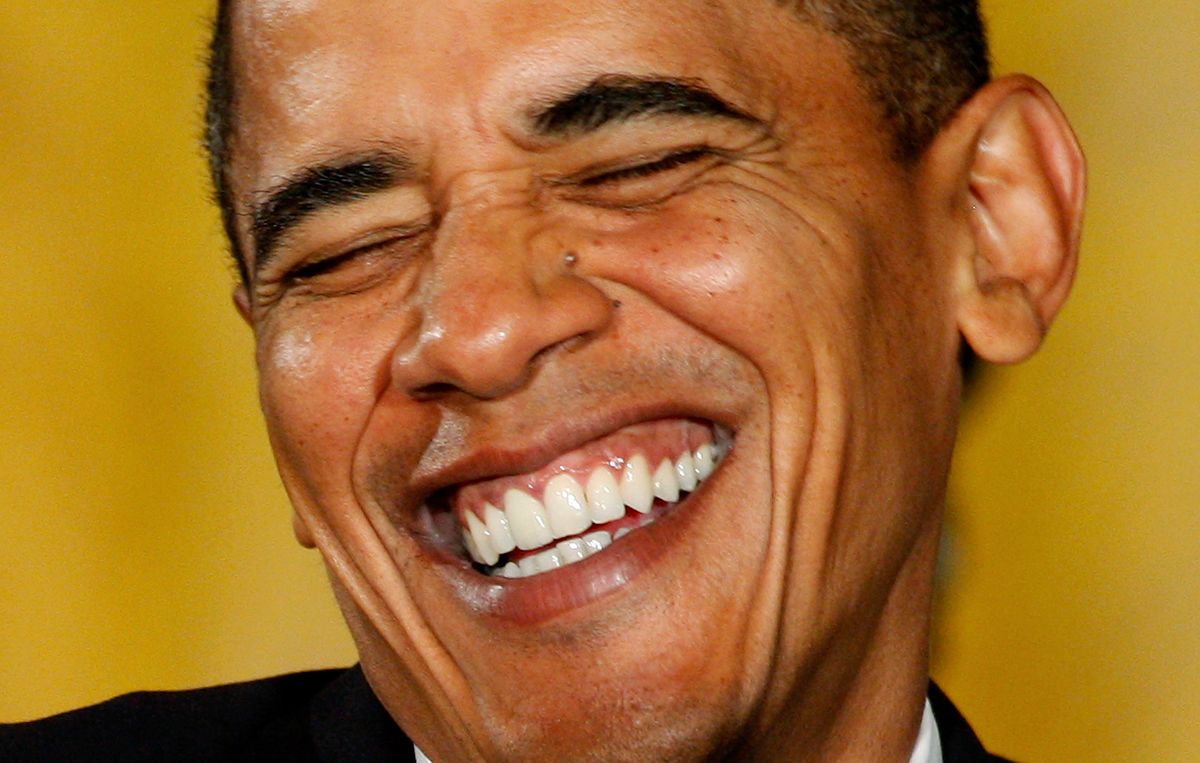

And voila -- the Obama narrative changes. The man who came into office right in the middle of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression (as compared to, by the way, FDR, who had the good fortune to be elected after the bottom had already been hit), comes to be seen as the politician who presided over an recovery while expanding healthcare for millions of Americans, reducing the number of nuclear missiles on the planet, and -- heavens to betsy! -- lowering taxes.

So what, realistically, are the chances for a good 2011? The crystal ball is foggy as hell, but the safest thing to say is that if the U.S. economy avoids hitting an iceberg, chances are good that it sails into balmy waters, sooner, rather than later. There is, of course, a huge "if" in that sentence. Right off the bat, there are at least three obvious sources of concern -- the housing market, Europe and energy prices.

On the housing front, mortgage delinquencies, for the time being, appear to have peaked, and pending home sales, existing home sales, housing starts and new home sales are all moving up off the bottom of their disastrous downcycle low points. But home prices are still falling and the backlog of unprocessed foreclosures (legitimate or fraudulent) is intimidating. Further price declines could put renewed pressure on homeowners teetering on the edge, and take the wind out of both consumer spending and job growth.

Depending on which day you check, Europe is either on the verge of cascading sovereign defaults and a banking crisis that will once again shake the world, or cobbling together a shaky rescue package for beleaguered European Union weaklings that wards off of a true systemic crisis. The best minds of the econoblogosphere keep dashing their brains against these Old World imponderables, and consensus is nowhere in sight. But there seems little question that a scenario in which Spanish sovereign default threatens the financial viability of German banks would not play well with global markets. If we learned one thing from the 2008 financial crisis, it's that the interconnectedness of global markets creates profound vulnerabilities. Subprime mortgage speculation in California helped crash the European economy. The favor could easily be returned.

And then there's the ever popular price of oil, which is rising again. The 2007-8 surge in oil prices played a critical role in pushing industrialized economies into recession. If the U.S. economy does start barreling forward, we could see a rerun. It could become an all too familiar and discouraging narrative for the 21st century -- constraints on the supply of cheap energy act as a capacity regulator that chokes off economic growth every time the business cycle starts hopping. Who knew the Industrial Revolution would ultimately prove to be so ironic?

Any single one of these factors could be a deal-breaker for U.S. economic growth, not to mention a combination of two or more. And still more wild cards wait in the wings -- a disastrous Chinese property crash, say, or surge in inflation that inspires the bond vigilantes to start shunning U.S. Treasuries. The global economy is a scary place and there are no guarantees. Despite accomplishing some good things, the Dodd-Frank banking reform bill certainly did not fix the fundamental flaws in how we organize our economy.

But the resilient business cycle has a life of its own, irrespective of the greater threats. So let's just suppose that in 2011, we avoid all the icebergs and the U.S. is rewarded by a self-sustaining, self-encouraging follow-through on the positive indicators that emerged in late 2010. Some normally circumspect economy watchers are already predicting some startling possibilities for the year. Calculated Risk, whose downbeat predictions for the year just passed hit remarkably close to the mark, suggests that the U.S. might see job growth in 2011 ranging from 2 to 3 million! If the higher end guess is accurate, we would experience one of the best years for the U.S. labor market since the go go '90s! Imagine if Obama's third year saw more robust job creation than any single year of George W. Bush's presidency. You heard it here first.

And yet, even that might not be enough to change the political dynamics. According to Calculated Risk, the U.S. economy needs to add about 125,000 jobs a month to keep up with population growth. But to make a dent in the unemployment rate -- to make real inroads on the 6.3 million Americans who have been out of work for more than 26 weeks -- the monthly number would have to be substantially higher. And with labor participation rates -- the number of people working as measured against the total population -- currently stuck at historical lows, any real improvement in the job market would undoubtedly encourage millions of Americans who have previously given up looking for jobs to get back in the market, which could paradoxically result in a higher unemployment rate even as the economy improves.

Which would bring the Obama administration back to square one. If the unemployment rate doesn't fall, it doesn't matter what the stock market does or whether inflation is contained or what the numbers for regional manufacturing production in New York or Philadelphia suggest. The politics of high unemployment crash every Obama party. You could make a case that Bill Clinton escaped impeachment because, by and large, the general public cared a lot more about the booming job market than who the president had sex with. As long as unemployment stays near 10 percent, the heat on Obama will continue to simmer.

Shares