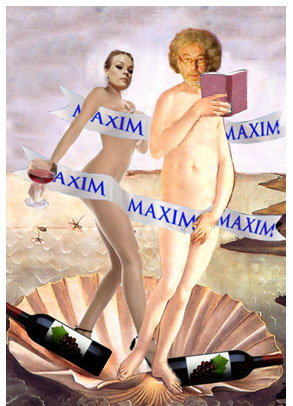

At a center-stage lectern in Manhattan’s soaring Gotham Hall, magazine publisher-cum-poet Felix Dennis was sending one out to the ladies in the room. “This is about the obsession some of you have with plastic surgery,” he said, shaking his gray mane sadly. He gave his wine-soaked audience a sly grin and raised his hand as if to testify. “Now I know that … I am the publisher of Maxim,” he confessed, acknowledging that the impossibly perfect skinnies featured in his magazines might contribute to the culture of self-loathing that makes cosmetic surgery so popular with women. But, he hastened to add, “the beautiful young movie stars on Maxim’s covers have been slightly changed by air brushing, not by steel scalpels.”

Then Dennis, who looks like Jerry Garcia if Jerry Garcia had had a permanently scarring encounter with an electric socket, launched into a fevered reading of “To a Beautiful Lady of a Certain Age,” his brown spectacles just barely hanging on to his bearded and rapidly bobbing face.

“Lady, lady do not weep

What is gone is gone. Now sleep.

Turn your pillow dry your tears,

Count thy sheep and not thy years…”

Dennis had built up quite a head of steam by the third stanza, which begins, “Lady this is all in vain/ Youth can never come again.” But then he really let loose: “NIP AND TUCK ‘TIL CRACK OF DOOM!” he thundered. “What is foretold in the womb/ May not be forsworn with gold — Nor may time be bought and sold!”

The six black-clad members of the Royal Shakespeare Company flanking Dennis on either side of the stage smiled nervously. A listener in front of me whimpered, “I’m scared.”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Until now, Felix Dennis, 57, has been best known as leader of a soft-core newsstand revolution, and one of the publishing industry’s most terrible enfants. The publisher of Maxim, Stuff, music magazine Blender and news digest the Week began life as a wannabe blues singer in a London suburb. A horny young buck in the swinging ’60s, he started his climb through media’s ranks by selling copies of hippie magazine Oz on King’s Road. (In 1970 he was tried for conspiring to corrupt the morals of children with an edition of Oz that depicted an orgy on its cover.) Dennis’ stable of magazines would later be populated by periodicals on considerably less titillating topics: cars, computers and world news. But what made Dennis famous — besides his public bout with crack addiction, reports of his multiple simultaneous girlfriends, and his 1996 admission to the Guardian that he preferred non-penetrative sex — was his popularization of toned-down skin rags aimed at advertiser-friendly young men.

But now, the man who made a fortune on unsentimental product is using his lucre — according to the New York Times his net worth is between $300 million and $700 million — to fund a 14-stop tour in support of “A Glass Half Full,” his first collection of poems on topics like aging, terrorism, death and faithful mutts.

“There are tough poems in here that might be very uncomfortable for some people to read,” Dennis told me on the afternoon before the reading, sitting at a Dennis Publishing conference table in Midtown Manhattan, wolfing a roast beef sandwich and smoking Silk Cut cigarettes. “But I don’t think there are sentimental poems in here, and if there are I would like you to point them out to me.” Dennis defended “An Old Dog Is the Best Dog,” his loving ode to an aged canine, claiming, “When I read the old dog one, as I will tonight, you’ll see I don’t deliver it in a sentimental way. In fact, you can sometimes hear people sucking in breath when I actually call a female dog what it is.”

Sure enough, later that night, you could smell the old dog coming a mile away. In a special installment of the tour, members of the Royal Shakespeare Company had agreed to mix readings of Dennis’ work with those of the Bard for a $200-a-head benefit for the theater troupe. Actor Mark Hadfield came to the mike clutching a large stuffed dog and read Launce’s exhortation to his mongrel from “Two Gentlemen of Verona.”

“O, ’tis a foul thing when a cur cannot keep himself in all companies!” lamented Hadfield as Launce. Then it was Dennis’ turn to prove his unsentimental mettle.

An old dog is the best dog,

A dog with rheumy eyes;

An old dog is the best dog

A dog grown sad and wise,

Not one who snaps at bubbles,

Nor one who barks at nowt,

A dog who knows your troubles,

A dog to see you out.

But the poet’s subtext became clear as he spat out the second verse, which began, “An old bitch is the best bitch.” Dennis emphasized both instances of the word “bitch.” As promised, people in the audience sucked in their breath. Or spat their wine into their napkins. It was hard to tell.

When I asked the childless, never-married Dennis how his feelings about women had changed over the years, he said, “I believe I’ve always been immensely generous with women. I was brought up by a single mother — a very unusual thing in the 1950s. So I didn’t have to be taught by Germaine Greer about equality in work and sex. My mother was earning the money in my house.” Dennis, who worked with Greer on Oz and appointed former Marie Claire editor Clare McHugh to be Maxim’s first chief, added, “I don’t have some of the concerns that I see some men having. For example, if I didn’t own my own company, it wouldn’t be the remotest problem for me to report to a woman.”

When I asked him about his repeated use of the possessive construction “our women” in his poem “The Summer of Love,” about the hedonism of 1967 (“And we scolded non-believers and we taunted the police./ And our women made us teas while we puffed the pipes of piece … And we lived in San Francisco, or else in Notting Hill,/ And we made a lot of babies though our women took the pill”), Dennis said it was intentional provocation.

“That’s quite deliberate when you’re writing poetry,” he said, “when you think, That’s great and that’ll really upset some people! I’m gonna go and do it again!” Here he let out one of his frequent, self-appreciative staccato laughs, and recalled a day 30 years ago when the women working at Oz “got so fed up with all the guys getting all the glory that they went and started their own magazine called Spare Rib. Literally, some of them were the secretaries, and we were all stunned. We just couldn’t believe it! Where had they gone?” Here Dennis looked under the table, in mock confusion, seeking the secretaries of his youth.

One on one, at least with a female reporter, Felix Dennis seemed pretty tame: charmed to be asked about his verse, but almost shocked when questioned about whether it’s getting him laid. He recovered enough to say, “When you’ve got hundreds of millions of dollars, getting laid is not your problem,” and giving another loud laugh before continuing: “I’m getting older, you know?” He offered a parable about a Chinese fisherman realizing that he has missed the tide and continued, “The tide has gone. You start to think, Thank Christ for that, now I can have a decent conversation with a young woman without…'” Dennis trailed off.

“I’m 57 years old now. When I was in my 20s and 30s, if I didn’t have sex loads of times a week I’d think something appalling was happening. Now I tend to mock myself and even sex, because it’s not as important to me as it used to be.” But Dennis was quick to clarify, using his stiff palm to chop at the table for emphasis: “When it’s important, it’s very important! But for many years I would argue that even making the money was to feed the sexual appetite. That is certainly not true anymore.”

His most voracious appetite right now appears to be for readers of his poetry, of which he claims many. When “A Glass Half Full” was published in England last year, it sold through its 10,000-copy print run. Miramax Books has printed 15,000 copies here. Even with corporate offices around the world, homes in Warwickshire, England; Connecticut; and Mustique, the tiny sandbox of the ludicrously wealthy, Dennis identifies more strongly with his hardscrabble beginnings, and fancies himself a bard of the masses. He burbled happily about the “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of letters and e-mails” that come “literally from dentists and housewives and doctors and just the weirdest broad catholic readership.”

As Dennis commented at the reading, “The English are not unused to dealing with a certain level of contradiction.” A cur who is in fact able to keep himself in most companies, Dennis is a man of contradictions: a Mustique dweller who sells to the proletariat, a peddler of impossible female forms who chides women about self-alteration, a soft-core balladeer, a recovering crack addict who passes time with the Royal Shakespeare Company.

“Some of [Dennis’ poetry] is quite good,” RSC actor Sean Bean told me at the reading after-party, before actress Samantha Bond bade him goodnight with a kiss on the cheek and a whispered “Bizarre!” that seemed to sum up the evening.

But a collaboration with the world’s preeminent dramatists hasn’t rid Dennis of the chip on his shoulder about his perceived exclusion from the poetry community. I had no more said, “So about your poetry…” than Dennis launched unbidden into a minutes-long monologue in defense of metered verse. “I’m putting forward the alternate view, that you do not have to write free verse to be a great poet,” he said, after expressing his enthusiasm for Donne, Herrick, Browning and Keats and his distaste for free verse. Dennis’ poetry — which is actually pretty fun to hear out loud — recalls the work of Shel Silverstein, whose poems were filled with satisfyingly rhymed ditties about the harmless, if dark, desires of childhood.

Like continuations of Silverstein’s poems, Dennis’ focus on some of the grim realities of adult life: sexually active grandmothers, firing people, blowing off business meetings in favor of a quickie, cocaine. He employs classical forms — quatrains, sonnets, ballads, sestinas — which he taught himself after the muse struck him four years ago. He’s also rewritten some nursery rhymes: In one, Jack and Jill and the hill and the pail of water all sue each other. There’s also “The House That Crack Built,” and the tinfoil-on-teeth “Baa Baa AIDS Sheep,” which does not appear in “A Glass Half Full,” but which Dennis read in front of the RSC.

Dennis’ poems always rhyme.

Tom Wolfe, who compares Dennis’ work to Rudyard Kipling’s on the jacket of “A Glass Half Full,” and attended the RSC reading, acknowledged that Kipling’s poems are not regarded with fondness by the poetic establishment. “But he wrote really good stuff, and of course above all Kipling realized the power of rhyme and meter,” said Wolfe.

“A hundred years ago if you had tried to write free verse people would have looked at you and said, ‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?'” said Dennis. “And now the shoe is on the other foot. Now if you write long quatrains or pantoums, you’re the idiot.” But, Dennis argued, there is some question as to where the idiocy lies. “Free verse has presided over a monstrous decline in the interest in poetry … And yet as soon as a guy writes a book based entirely on those [classical] forms, people say, ‘Who the hell does this guy think he is? This guy is just a rich idiot.’ Maybe they’re right. But not, apparently, to thousands and thousands of people who read this book and write to me.”

Dennis is known for his explosive temper — just ask the security guards in the Dennis Publishing building, who pursed their lips and shook their heads in warning when I told them who I was there to meet. But his rumpled, lumpy look diminishes the fear factor. Then there’s the fact that while describing a recent reading in Detroit, where he claims two luscious young bawds appeared backstage and started fooling around, he said, “I did enjoy it, but I think I knew in my heart of hearts that nothing was going to happen. They were just pretending this was a big rock ‘n’ roll tour.”

Dennis also said that overcoming his crack addiction has left him few vices save smokes and wine. “I’ve always been attracted to walking on the edge of the pond on the ice,” he said. Now, he claimed, his precarious ice walks come at moments like the New York reading. “Going onstage with these hugely professional actors and doing all that kind of stuff — I get very, very nervous, because I am outclassed and outgunned. I am not used to being in a room of any kind being outclassed and outgunned.” Not exactly the kind of danger once provided by the crack pipe, I protested. “No, they are different kinds of discomfort,” he acknowledged with a smile.

Still, Dennis hasn’t exactly lost his edge. This is not a guy you’d want to compare sexual track records with — or, even in these, his 12-step days — attempt to drink under the table. But he sure seems to have begun the fade into baby boomer fuzziness. Felix the Cat is becoming Felix the pussycat. He’s still making mass-marketed nubile skin available front and center on newsstands. But he’s also taken up softer projects — like the poetry, yes, and the huge forest he’s planting in Britain, and the Garden of Heroes at his home in Warwickshire, which includes sculptures of Bob Dylan, Dorothy Parker and Dennis himself. It’s as though whatever was dangerous, fractious and maverick about him has started to melt and blur slightly.

It is no wonder that Dennis is so distressed by my suggestion that his poetry is sentimental. Back in the conference room, when he defied me to name a poem in “A Glass Half Full” that exhibited the sentimentalism he so clearly loathed, I looked at my notes and told him that “A Silent Prayer…” had been the one that had prompted my question.

For books, old dogs, and hissing logs, For letters left a week; For bells not rung, for hymns unsung, For mice that softly Squeak; For dumbstruck snow and tears that flow In silence down a cheek.

“Mmm,” said Dennis, thinking hard. “Well, I would say that that is the one poem in the book that tips furthest toward falling over the cliff of sentiment into the abyss of sentimentality. I think I’d accept that as criticism.”