Tori Amos has always been a cover song connoisseur. Early in her career, she drew raves for her careful, piano-driven takes on Nirvana's "Smells like Teen Spirit" and Led Zeppelin's "Thank You." On tours, she's known for covering a wide variety of artists, including George Michael, INXS, Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles, and Kansas.

On September 18, 2001, Amos released her most ambitious covers selections to date: a full-length album, "Strange Little Girls," featuring her takes on songs written by men. More than that, however, the collection offers an intriguing premise: What if some very famous songs by very famous men were instead centered on and about women?

This premise could easily have become quite gimmicky. However, Amos' empathy for the songwriting subjects makes "Strange Little Girls" a quiet, subtle triumph. That's evident most on a superlative cover of Lloyd Cole & The Commotions' "Rattlesnakes." The song features a main character named Jodie, who "wears a hat although it hasn't rained for six days" and packs a gun "on account of all the rattlesnakes."

Cole is himself an empathetic writer, and so his character sketch of Jodie offers telling details ("her neverborn child still haunts her") that explain her behavior. Ever perceptive, Amos picks up on Jodie's heartbreak; her voice drips with sadness and understanding, ensuring the cover ends up deeply affecting.

Vibe-wise, however, "Strange Little Girls" felt like a continuation of her 1999 double album, "To Venus and Back," which was heavy on atmospheric electronic elements. Her version of the Beatles' "Happiness Is a Warm Gun" offers sampled news snippets and keyboards that resemble experimental electronic compositions, as well as guitarist Adrian Belew adding the occasional jolting riff.

Belew is most effective, however, on Amos' languid cover of the Velvet Underground's "New Age," when his jagged electric bolts emerge as she sings the line, "I'll come running." That nuance crops up all over "Strange Little Girls" offers many moods. "I Don't Like Mondays" is sparse and haunting; 10cc's "I'm Not In Love" is menacing and ominous, playing up the song's obsessive side; and on "Enjoy The Silence," she doubles her vocals, making the song feel more like a heart-to-heart conversation.

The album's namesake song — and most upbeat, straightforward musical moment, as it features tumbleweed keyboards — is "Strange Little Girl." The 1982 single by the Stranglers featuring a protagonist who's figuratively lost and trying to find her place in the world: "Strange little girl / Where are you going? / Do you know where you could be going?" The word "strange" is an interesting one to describe a person. The term isn't always wielded as a compliment; in fact, it's a verbal side-eye to convention. "Strange" is a close relation to "peculiar," another vaguely antique-sounding words that connotes someone who's offbeat and different. That Amos called the album "Strange Little Girls" — plural — is even more telling: These are a collection of offbeat people who don't fit into any sort of neat, tidy mold.

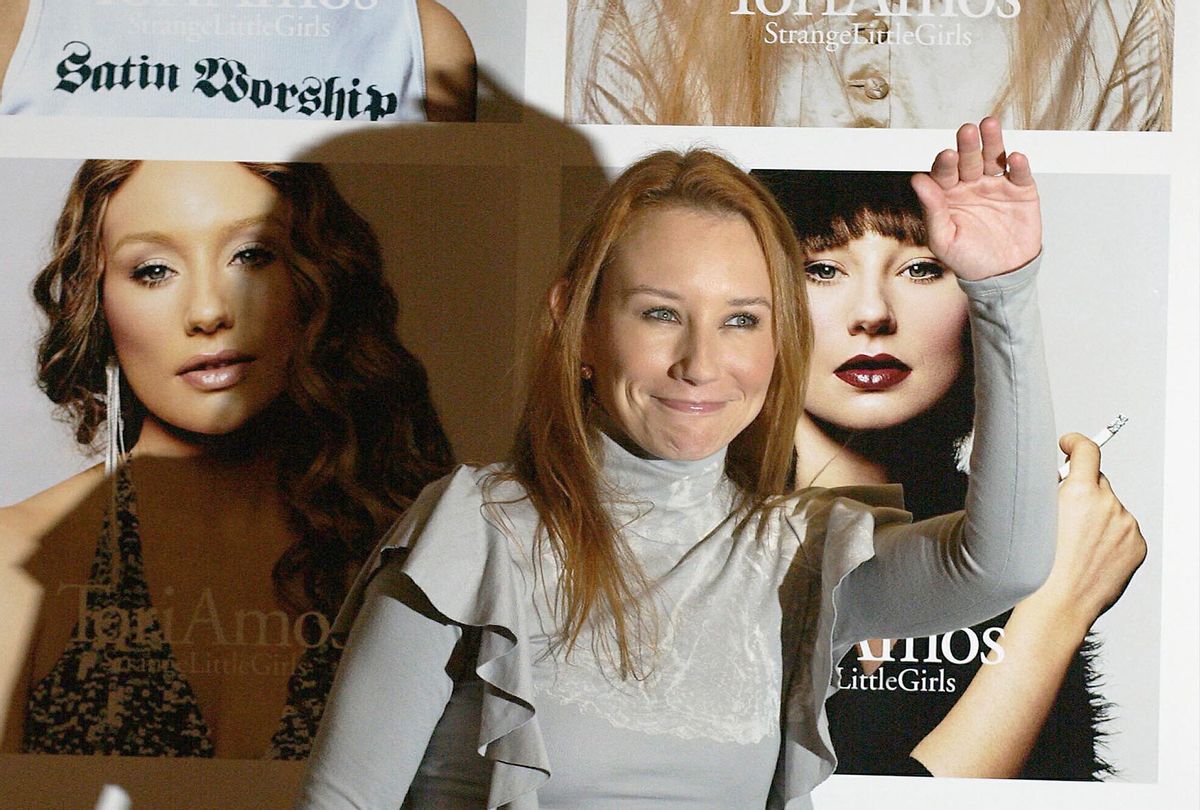

Fittingly, for each song on "Strange Little Girls," Amos portrayed a different woman. The liner notes even feature her photographed in costume, dressed up as these characters. The "Rattlesnakes" Tori has straight blonde hair and a KISS jacket. "New Age" Tori looks like a hipster librarian, with dark hair flipped at the ends and cat's-eye glasses, while the titular character has dramatic eye makeup, a shag cut, and a shirt that says, "Satin Worship." And "Real Men" Tori is tomboyish and defiant, in a power outfit: a white suit and wide belt.

In a 2001 interview with Rolling Stone's website, Amos detailed how the album's characters came about. "I did know that as I began to deconstruct each male song, a different woman seemed to have access to me," she said. "There was a trade; there was an exchange. If I were going to take this on board and deconstruct it, and get into these men and hang in their heads, then a woman had access to me, and that really surprised me."

Elsewhere in the conversation, she mused about who these women were and from where they came. "Are they the anima of the writers? I don't know. Are they the girls themselves personified? Not in all cases. Each woman has a very different relationship to her song. Some women are implied, some women are clearly there, written into the song by the male writer."

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Unsurprisingly, "Strange Little Girls" connects most strongly on songs where the women are implied, because the vagueness allows Amos' creativity to soar. On a roaring "Heart of Gold," which is as noisy as Young's guitar hurricanes, Amos saw twins — or "economic espionage gals," as she puts it to Alternative Press — who "infiltrate corporations and access information and send it somewhere else. Good or bad, it depends what side you're on." This backstory certainly isn't obvious from listening to Neil Young's song, which is a loose, weary meditation on searching for meaning in life and the self. However, Amos' vision certainly complicates what the song's reference to a "heart of gold" could mean.

Then there's Slayer's "Raining Blood," a song about someone mired in purgatory after being jettisoned from heaven; the implication is that it's somewhere he doesn't want to be. Amos has a different view: Instead, she envisions purgatory as a place of shelter, a refuge for a badass with supernatural tendencies. "She's a French Resistance woman whose sister was killed," she told Alternative Press about the "Raining Blood" character, who sports a jaunty beret and holds an ashed cigarette. The woman "knows myths and is calling on power and working on alchemy" in response, however: "She went to the underground after the death of everyone she knew."

Amos has spent a large portion of post-"Strange Little Girls" career writing songs about forgotten real-life women or historical figures. There's something equally poignant about Amos giving life and dignity to these fictional women by fleshing out their personalities and portraying them as three-dimensional characters. In countless classic songs, women are more like unfilled-in outlines, known only as "she" or "her." In addition to being nameless, these women are blank, ghostly vessels onto which emotions are projected. Life happens to them; they're not people with their own agency. On "Strange Little Girls," Amos offers complex personalities and complicated plot details — broadening musical history narratives that are often male-driven and frustratingly narrow.

That doesn't mean "Strange Little Girls" follows a strict binary. For example, Amos pairs Joe Jackson's "Real Men," a song with pointed observations about gender, sexuality and stereotypes, with a character that's deliberately androgynous; her solemn, relatively unadorned reading of the song asks questions rather than provides answers.

But nowhere is Amos' perspective clearer than on her take on Eminem's "'97 Bonnie and Clyde." This particular cover received the most attention at the time; lyrically, it's a graphic song in which the rapper describes disposing of his wife's body in front of his toddler daughter. (Notably, the dead woman is only referred to as "Mama.") Amos, however, reclaims the song and its violence from Eminem. Affecting a whispery, raspy voice, she narrates the song from the perspective of the mother, while dramatic, string-heavy music that resembles a silent movie score churns around her. The murdered woman's life is centered and important; she's given a voice to foreshadow the consequences of the crime.

As it turns out, Amos envisions the titular character as the daughter who witnessed the crime, only "all grown up, having to deal with the fact that she was an accomplice to the murder," she told Alternative Press. "She's a dichotomy of things because she's divided." The "Strange Little Girl" here is (understandably) left confused and bereft. Yet Amos' delivery on the song feels like a soft landing, or more like she's comforting the daughter. Of course, Tori is deeply protective of all of the "Strange Little Girls" on this album — and that's why it's a covers collection that endures.

Shares