Most experienced Net users filter forwarded e-mails according to at least one simple rule: Sad stories probably aren't true, and really sad stories that ask for donations aren't just false, they're probably scams or viruses.

Last month, online friends of 19-year old leukemia patient "Kaycee Nicole" were crushed to discover that the plucky teenager they'd been sending Beanie Babies and Amazon gift certificates to for a year was actually a healthy woman named Debbie Swenson. Swenson wasn't asking for donations, but her fictional accounts of a bout with cancer earned "Kaycee" hundreds of devoted fans around the world. The Kaycee Hoax, as it's now known, confirmed the need for suspicion on the Web, but it also points to more general questions. Is there room on the Web for pleas from people who actually need help?

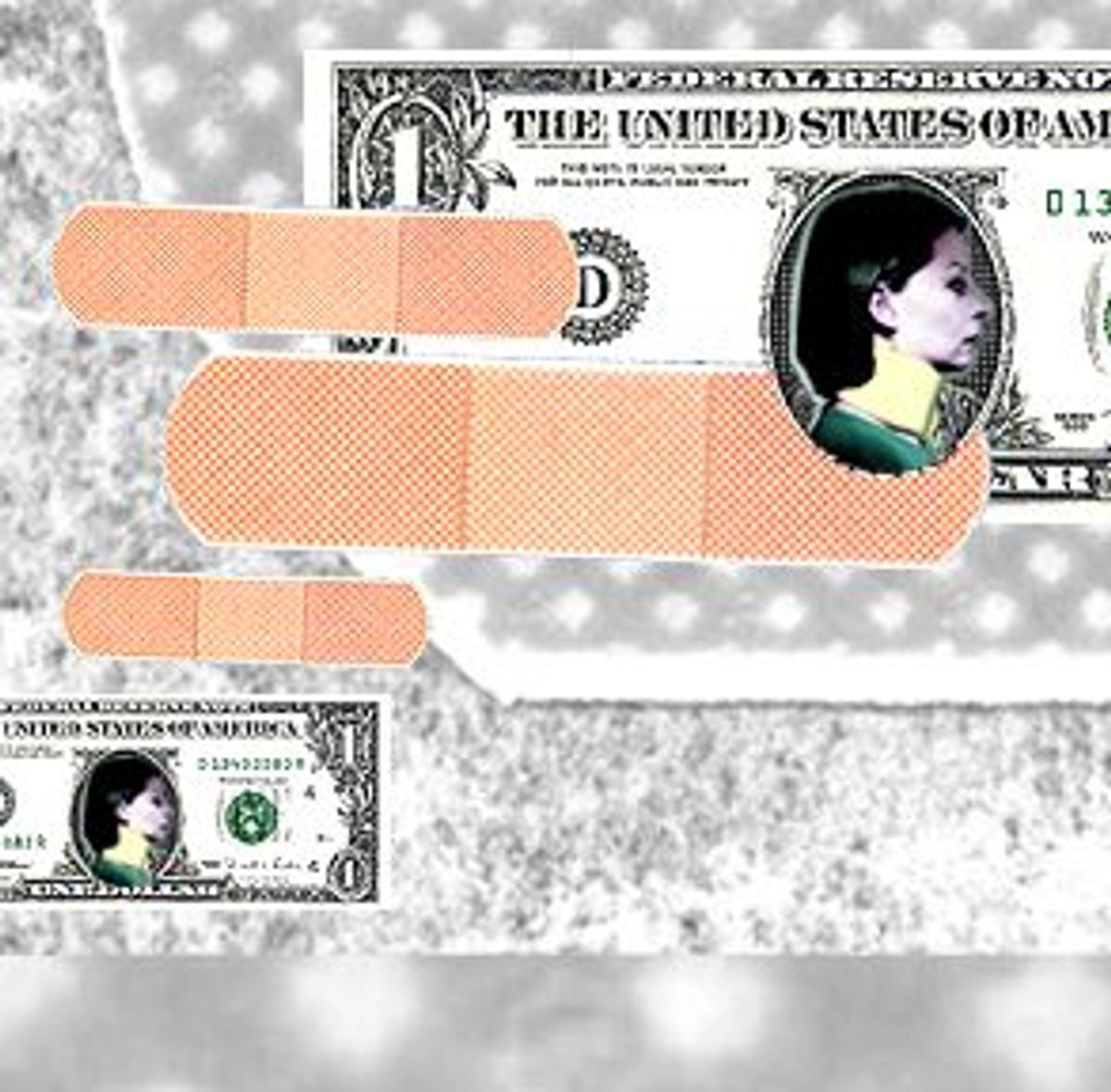

Keith Dawson, founding author of the 6-year-old newsletter Tasty Bits from the Technology Front, thinks so. He's just launched a not-for-profit corporation called Friend Indeed, which aims "to collect and distribute donations that enable the lives of worthy people."

"I have some reputation capital banked," says Dawson, whose weblog has earned several honors, including, most recently, a listing in Forbes' "Best of the Web 2000" feature. "This is the best way to spend it." The Friend Indeed program is meant to ensure that well-meaning Netizens don't get scammed again, Dawson writes in an e-mail that is currently circulating.

"Recently the Kaycee Nicole hoax ratcheted up the level of skepticism that Netizens will bring to any sad tale they read online. Read on with skepticism if you must, but please take my word that the story is true and the need is urgent."

However noble his intentions, Dawson may not succeed in proving the Net skeptics wrong. Even Dawson -- whose nonprofit promises to vet needy cases to ensure their veracity and need -- could have done a little more homework.

The Friend Indeed program launched with the case of Marcia Blake. According to Dawson's e-mailed plea for help and Blake's own account, a doctor botched Blake's January 2000 hip surgery in San Diego, and before a second operation could fix the problem, Blake's Kaiser Permanente insurance ran out. After going through Kaiser's complaint department and to California's HMO regulators, both of whom rejected her claims, she is now back home in Santa Fe, N.M., without insurance and without the ability to pay for surgery, which would cost about $50,000. Because Blake has been "uninsured and uninsurable" since she left California on Aug. 31, as she writes in her online plea, every day that she goes without surgery brings her closer to being unable to walk, permanently.

On April 4, Blake turned to the Net for help. She decided to go "outside the system," posting her story in an online forum and e-mailing everyone she knew. Dawson was on the list. She'd been one of his "irregulars" -- people who occasionally tip him off to technology news -- and since he'd known Blake for about three years, the plea carried credence. She seemed like the perfect first candidate.

Marcia Blake is in a dire situation, that much is certain. But a closer look at the details of her case reveal that it's not as simple as the e-mail makes it out to be.

Kaiser Permanente confirms that Marcia Blake is no Kaycee Nicole: She does indeed exist, a spokesman says. According to Kaiser, Blake had hip surgery last year and scheduled another appointment with a surgeon, which was cancelled, as Blake claims. Kaiser says that the appointment was for a consultation about the surgery, while Blake argues that the surgery itself was scheduled for late August. Both sides agree that the doctor cancelled the appointment days before Blake left for Santa Fe, leaving her without nearly enough time to reschedule.

But Dawson may have gone too far when he wrote in his e-mail, "She moved back to New Mexico, uninsured and uninsurable." He says he got this information from Blake, and never tried to verify it, figuring that his friend's version of the facts must be true. Had Dawson dug around more, he would have found a slightly different story. Both Kaiser and Blake (who clarified her situation in a telephoned interview) agree that she didn't actually leave uninsured. Blake was covered (under COBRA) through Oct. 1, two months after she left California.

Why didn't she reschedule the appointment while she was still covered? Blake says she didn't bother because she believed that she'd be covered until December, because she was busy trying to rebuild her own business after leaving a start-up, and because she didn't yet know that waiting would increase her chances of losing the ability to walk. Still, she could have flown back to San Diego, and Kaiser says it would have paid for the surgery that she wanted, a point that she did not mention in her original online plea and that Dawson failed to discover.

As for the "uninsurable" claim, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which Congress passed in 1996, prohibits insurers from denying coverage based on preexisting conditions. Blake says that she used the word "uninsurable" because she heard HMOs don't comply with the law, and that even if they do, they won't pay to fix something that another doctor allegedly screwed up.

Blake has formally approached only one HMO, Lovelace, and while she failed to determine whether it would cover more hip surgery, she admits that it did offer to cover her. Lovelace wouldn't comment on Blake's claims, but noted that coverage is determined on a case-by-case basis, and that it is possible to get coverage for pre-existing conditions. Blake says the premium Lovelace quoted was steep -- at least $1,200 per month. But even at that rate, two years of coverage would still be cheaper than surgery.

Unlike the Kaycee Hoax, this is not a case of deliberate deceit. Bewildered by the bureaucracy of a giant HMO, a move, a job change and a potentially crippling injury, it's no wonder Blake found herself in such a state; her omissions don't impugn her honesty so much as show the level of her desperation. Indeed, none of these details diminish the fact that Blake's case is tragic, nor do they suggest that Blake doesn't need help, fast.

Dawson, meanwhile, can hardly be blamed for taking a friend's word. But his oversights illustrate a larger problem.

In an environment full of doubting Thomases, even minor omissions and unintentionally glossed-over facts only reinforce the skepticism that the Kaycee affair and similar hoaxes have instilled among Web users. If Net users are ever to overcome their tendency to view all sob stories as scams, it may take some rigorous application of the old saw, "Trust -- but verify."

Shares