Has Michael Haneke changed, or has the world of mainstream film inched closer to his uncompromising aesthetic? Probably a little bit of both. It’s trite but entirely accurate to say that I never expected to see the director of such violent and/or confrontational films as “Caché,” “Funny Games” and “The Piano Teacher” on the stage of that big theater on Hollywood Boulevard, accepting one of those little gold statues. Then again, Haneke has never before made a film that feels as intimate and personal, or as universally accessible, as “Amour,” a wrenching tale of love at the end of life that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes last spring and is widely expected to capture the foreign-language Oscar as well.

That nomination for “Amour” was entirely expected, but it surprised the entire movie world to see Haneke also nominated for best director, while more familiar names like Ben Affleck, Kathryn Bigelow and Quentin Tarantino were not. Meanwhile, Emmanuelle Riva, the film’s 85-year-old star -- and a leading lady of French film in the 1960s -- became the oldest woman ever nominated for best actress. So it is that Haneke, a 70-year-old Austrian intellectual who is both a revered and a controversial figure in international cinema, is having his pop-culture moment (or as close to one as he’s likely to get).

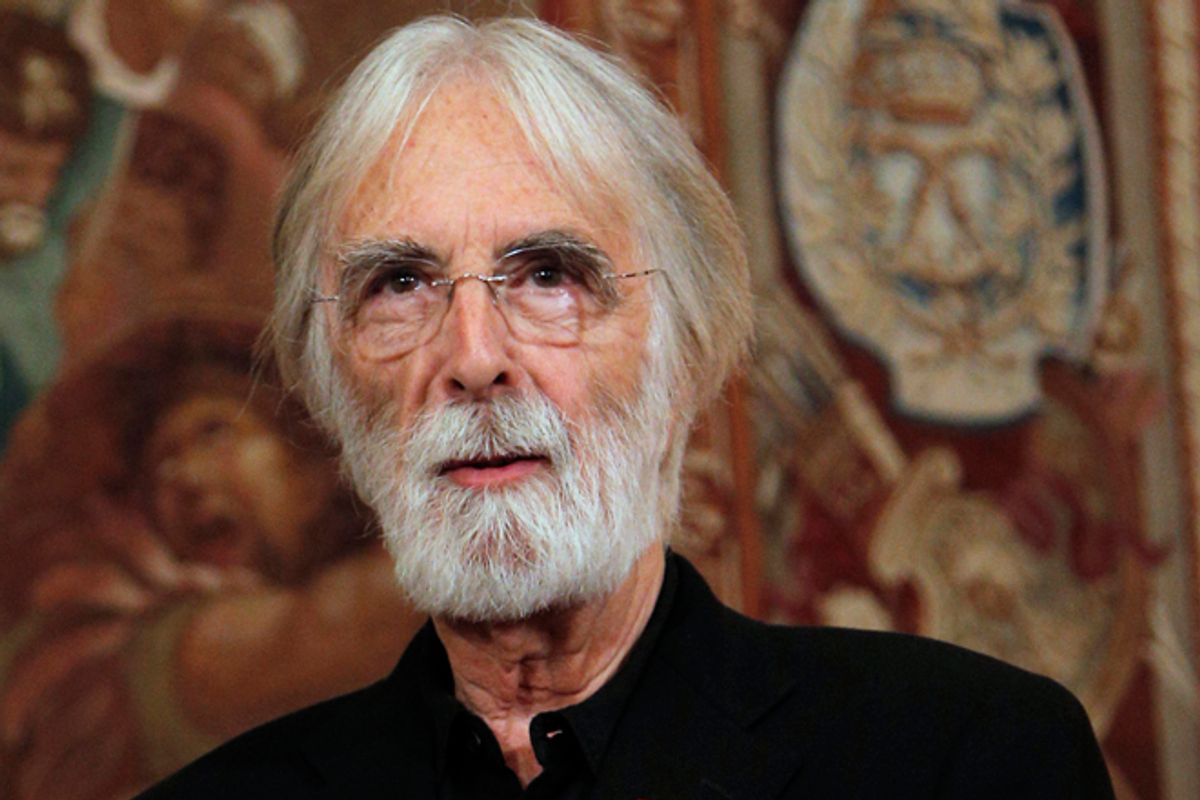

A silver-haired, professorial type who favors tweed jackets and a distinctly bemused demeanor -- and who was born in Hitler’s Germany -- Haneke seems like a severe personality at first, but is not entirely devoid of wit or good humor. I’ve gotten at least one laugh out of him the two times I’ve met him – once when I challenged him on the central mystery of “Caché,” which I contend cannot be solved within the film’s fictional universe. (Haneke has consistently declined to endorse that theory, or any other.) This time around, he told me that he, Riva and Jean-Louis Trintignant had a relaxed and enjoyable time together, making a movie that looks the harshest realities of old age and death right in the face.

Still, there’s no question that Haneke represents a tradition of cinema that seeks to challenge the viewer, to demand our full attention, and to stretch the borders that separate a film from its audience. After an early career as a playwright, stage director and writer for Austrian television, Haneke moved to filmmaking in his mid-40s. But the 12 pictures he has made as a director, beginning with “The Seventh Continent” in 1989, have demonstrated an extraordinary degree of technical and narrative power, often with a mysterious psychological undertow. He’s won the Palme d’Or twice – last year, and in 2009 for “The White Ribbon,” an ambiguous black-and-white fable of Germany before World War I – and has also been described, by his detractors, as a manipulative creator of “existential horror films.” (To which my response, more or less, is: Yes, and what's your point?)

Haneke favors long, static takes and uses music sparingly, and generally only inside the frame of the narrative. (Music plays a central role in "Amour," but there's no soundtrack as such.) While his films often feature acts of violence, he rarely shows them directly. His basic mode is one of apparent realism, but it is frequently interrupted by unexplained dreamlike incursions or direct audience confrontation. (In “Funny Games,” one of the bad guys stops the film and “rewinds” it at a crucial juncture, as if it were a VHS tape.) He isn’t much interested in film as entertainment, or in providing “pleasure” in the Pauline Kael sense. Asked about his own moviegoing tastes, he has said, “I'm interested in seeing films that confront me with new things, with films that make me question myself, with films that help me to reflect on subjects that I hadn't thought about before, films that help me progress and advance … For me, personally, I think watching a movie that simply confirms my feelings is a waste of time.” (Toward the end of this conversation, he told me he had seen Andrei Tarkovsky's "The Mirror" at least 25 times.)

As I wrote when reviewing the film in December, “Amour” is by far the most straightforward and gentlest of Haneke’s pictures, at least on the surface. Its portrayal of the relationship between Georges (Trintignant) and the terminally ill Anne (Riva), a pair of upper-middle-class Parisian retirees with high-culture tastes, is both realistic and affectionate. “Amour” does not involve a descent into sadomasochistic sexuality and madness, like “The Piano Teacher,” nor does it feature violent criminals who directly implicate the audience in their crimes, like “Funny Games.” But if Haneke’s darkest films involve three interlinked elements or themes – ordinary life interrupted by unexpected or unexplained acts of violence, the hidden costs of bourgeois privilege and European history, and the unstable conventions that govern a work of art’s relationship with its audience – all three are present in “Amour,” if at a subtler and quieter level.

I met Michael Haneke last September when he was in town for the New York Film Festival. We had coffee in a conference room at the Trump International Hotel on Columbus Circle, which felt rather like a setting he would have used to horrifying or ironic purposes in one of his early experimental movies, like “71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance.” Although he speaks English reasonably well, he always insists on speaking in German through an interpreter, which makes the interview process even more formal, fraught and generally Haneke-like. I should warn you that this interview contains a major near-spoiler about exactly what happens between Georges and Anne in “Amour” – I’m operating on the assumption that A) most readers will already know or suspect where the story is going; B) it doesn’t affect the power of significance of the film; and C) Haneke’s inside-out chronology provides major clues about the ending within the first few minutes.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this before, but when people see that Michael Haneke has made a film whose title is simply “Love,” they’re going to wonder: Is there any level of irony to that title?

No. [Chuckles.]

So it is a portrait of love?

You’re only presenting one aspect of love. To actually engulf every aspect of love, you need 50,000 novels and plays. I’m presenting one aspect of love, but I think an important aspect. I never would have dared to title the film “Love” if it had been dealing with a conventional love story, but in this context I think that the title gives a certain stress to the film, a power to the film.

In fact, the title was an idea of Jean-Louis Trintignant’s. We were having lunch together and I mentioned – I read to him a list of titles I’d been suggested, none of which I liked, and he asked, “Well, if the film is about love, why don’t you just call it ‘Love’?” And I thought it was a great idea.

Where did the idea of approaching an older couple in their last time together – where does that come from? Artistically, personally, philosophically …

The starting point for the film was an experience that I had in my own family. Someone in my family who I loved was very ill and dying and suffering, and I could do nothing about it. It was an awful experience. And that was the starting point for my film. The film isn’t about old age as much as it is about the question, “How do I cope with the suffering of a loved one when I’m impotent to do anything about it?” I couldn’t have dealt with the film by making it about a middle-aged couple whose child is dying of a serious disease. That would’ve been a tragic case, but it would’ve been an isolated case, whereas dying of old age is also tragic, but far from isolated. It’s much more common. And because of that context, it allows greater possibility of identification by the audience.

Yes, presumably this is a fate that will befall a great many of us, some version of this.

Not a great many of us, but every one of us. [Chuckles.]

Death, yes, that’s waiting for everyone. But I meant the possibility of a lingering illness, of a slow and perhaps agonizing death. I think that’s one of the most difficult things to think about, isn’t it? If one gets hit by a car or struck down by a sudden heart attack, I mean, that’s actually not as difficult to contemplate. My father-in-law had a heart attack and fell dead on the bedroom floor. In some ways, I think that was merciful.

That’s the kind of death we all hope for.

Obviously I should ask your actors this question, but did you get any sense that it was difficult for Trintignant and Riva to play characters who are at or near death? I mean, they are both over 80 – they are surely aware that the reality might not be far away.

It’s hard to say. I think, in fact, you would have to ask the actors that. Quite honestly, I didn’t have the impression that was difficult for them. I’m sure that when they read the script the first time, they were shocked by what they were facing, but like all professionals, I think they realized how gratifying playing such a role would be.

In fact, we had a lot of fun on the set! I’m not saying it was easy, but it wasn’t the case either that at the end of the day we were all moping and walking around with sad faces. There was another complication that made it harder for Jean-Louis, in that during filming he broke his hand. He didn’t break his hand, however, on set or while we were filming. As you can see in the film, he’s quite unsteady on his feet, so he asked to work with a physical therapist to prepare for the role, and while he was training with the therapist, he broke his hand. Because of that, not all the scenes were easy because of what they involved physically. It’s no fun shooting when you’re in pain.

Catharsis is a complicated concept and maybe a cliché at times, but given your background in theater and your intellectual background, I wonder if you think that’s useful concept in thinking about a film like this. Is there catharsis in vicariously living through something this painful?

I think that catharsis is an overly ambitious term. If a film manages to make spectators as viewers reflective for a few hours, if it manages to make them for a short time nicer to each other, more humane, then you’ve achieved a great deal. Catharsis is too ambitious. I don’t think, in today’s society, you can achieve catharsis with a book – uh, film.

Now, in some of your films – I would say in almost all your films – you seek to remind us at times of the artificial or constructive nature of what we’re watching. Most obviously that’s true in “Funny Games,” “Caché” and “The White Ribbon.” From your nodding, I assume you agree with that. [Laughter.] Do you think there’s a level of that present in this film?

No, I don’t think it’s present in this film, simply because it’s not the theme of the film. However, I’m convinced that I’ll return to those themes at some point.

I’m not entirely sure about that. There are a few moments where I wondered whether the naturalism, the straightforwardness of the film, perhaps has a few breaches in it. First of all, I was curious about the dream sequence, when Georges dreams that the apartment building is flooded and falling apart – and then is assaulted by an unseen figure.

That scene was important to set up the ending of the film. That was the productive means for the audience, because we’ve all had dreams, we know what that is. But the idea was to find an aesthetic way that would prepare so they would understand the ending. We’ve all had dreams. The other scene like that is the scene where [Anne] is sitting at the piano, playing piano. The camera then shows him turning off the CD player. Again, those two scenes were necessary to set up the ending. It introduces a meta-realistic level to the film.

I suppose you’ve already made this clear, but Georges is the central character, and to some extent the consciousness of the film is his consciousness. Arguably, being the person who is ill and dying is less difficult than –

As I said before, the starting point of the film – the theme of the film, if you want to reduce the film to a single theme – is how one copes with the suffering of the loved one.

Now, another element of the film that certainly could be entirely realistic, but some viewers may choose see it differently, is the bird who twice visits Georges in the apartment. It’s a pigeon, which is a species of dove, a powerful symbol in Christianity. I’m guessing you do not intend that as a religious metaphor. But some people may want to see it that way.

Every viewer is free to interpret the scene they want, and depending on how their spiritual education has prepared them.

That’s a – that’s a careful answer, yes. Even for you!

No, I really do try, in all of my films, to allow the spectator the greatest number of possibilities to bring in, to apply their own imagination. There are very – there are many different means to do so.

I was thinking about the question, then, of the presence or absence of religion in your films. You have the example of someone like Bergman, whom I know you admire – an atheist or agnostic who was nonetheless obsessed with religion. I assume you’re probably not a religious person, but the question seems largely absent from your films, at least until know. It’s as if you don’t love God, but you don’t hate him either.

I can say that already there have been several books published by theologians about my film. (Laughter.) My films raise existential questions, and it’s up to each spectator to decide whether belief or religion provides an answer to those questions. It’s really a question up to each spectator. However, my films don’t seek to indoctrinate the spectator. It’s up to them to choose their own answers, their own approaches to these questions. If they’re absolutely looking for a religious element in the film, then in this one you can see the scene where Jean-Louis Trintignant is playing the piano – he’s playing, in fact, a Bach chorale that’s based on a prayer. It reads: “I call on you, I beseech you, Lord Jesus Christ, in my deep distress.” So you can interpret that religiously if you like. It’s really up to each individual spectator.

This is a couple who are devoted to art – specifically, to music. For me, you see the history of Western culture as it came to us in the 20th century in their apartment. It’s so full of art and music and these artifacts of civilization, and it’s become conventional to say that art can provide the succor or the relief that religious faith used to provide. It’s not clear that in this film it does.

I agree with you. (Laughter.) The difference between religion and art is that art doesn’t offer answers, only questions.

When the pianist, her former student [played by Alexandre Tharaud, a genuine star pianist in the classical world], comes to visit them – that’s a very ambiguous scene. He’s shocked and upset to see her, and it seems as if the visit does not provide the connection or the moment of happiness that it might have in another kind of film.

You are perhaps right. I think when you are unexpectedly confronted with the suffering of someone else, then you do react in that way. You never react in the best possible way. You’re overwhelmed and you stiffen up. I think that his reaction is a realistic one.

Tell me about the painting or drawing of the bird – which certainly looks like a dove. Do we see that before we see the actual bird, or does that only appear after we have seen the bird? I wondered if you were playing a little game with us there.

Yes, of course. It’s one of the things that you enjoy playing with as a director, playing with those references, those repetitions, the indirect ones. I think that it’s important to offer the – as a viewer and as a reader, I like films and novels where you’re led to reflect on what you’ve seen. I think you have to make films in such a way where they bear repeated screenings and each time you see something new. Otherwise the film is dead. I’ve seen Tarkovsky’s “The Mirror” at least 25 times, and each time I discover something new.

I imagine so, yes. That’s a great film, but I’m pretty sure I’ve only seen it twice. Wow, that’s impressive! Do you mean to make us feel uncertain about Georges, Trintignant’s character, and his own mental condition? When he dismisses the young woman, the nurse, we don’t know why. We don’t know what she has done or not done, and we don’t know if he is justified.

Well, I think it is. I think she behaves very badly with Anne. She treats her very badly. For example, when she’s combing her hair, I think it’s very disturbing what she does. Outrageous. And I think he’s justified in throwing her out. It’s something that I came across frequently in my research, but also among my circle of acquaintances. People who were university professors in their previous lives who were treated like children. That makes me furious.

Still, even though he’s the person in the film who appears to maintain mental clarity, there are also questions about that. He leaves the faucet running when she has her first stroke or episode or whatever it is, and doesn’t seem to notice the powerful, insistent sound of running water.

I think that in a situation like that, then, yes, one could easily leave the faucet running when you’re in such a panic to help someone else. Similarly, if you’re at home, and someone calls you on the phone, “Come quickly, help me,” then it’s easy to forget – you leave the keys in your apartment in your haste to run out. I think I would have reacted similarly.

I don’t mean to suggest that this film is about a political issue, because it’s clearly not. But do you have feelings about the issue of euthanasia, such as is possible in the Netherlands under certain circumstances?

You’re right. The film does raise those questions, among others, but I don’t – as Michael Haneke, I don’t want to provide my own personal response to that, because I don’t want to create a user’s manual. I don’t want to indoctrinate the spectator or tell them how they should respond. As I’ve touched on before in our discussion, I’m seeking to allow as much as possible for spectators to form their own opinions.

And I suppose that applies, more than anything else, to what Georges finally does in the film. It’s about as morally ambiguous as any act committed by a human being could be, right? One could decide that it is absolutely the right thing to do and one could also decide that it was a terrible crime.

The way it’s presented could be seen in different ways, and that’s how it is in real life. Things can rarely be reduced to one thing or another. They’re always a combination – done for a combination of reasons, motivations. They can’t be reduced to a single theme or a single justification. Their behavior is the result of a bundle of contradictory aspects and motivations. That’s the job of art: to present in such a way as opposed to a science, or journalism, which seeks to identify individual reasons. I don’t want to reduce the explanation to a single idea or to a single motivation or to a single – you know …

[Interrupting the interpreter, in English:] Well, it is very complex. (Laughter.)

“Amour” is now in theatrical release nationwide.

Shares